A reader’s perception of a narrative’s reality is affected by emotions they aren’t even aware of, an experience created by the layers of worldbuilding.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

The emotions evoked in readers as they experience the story are created by the combination of mood, atmosphere, and subtext.

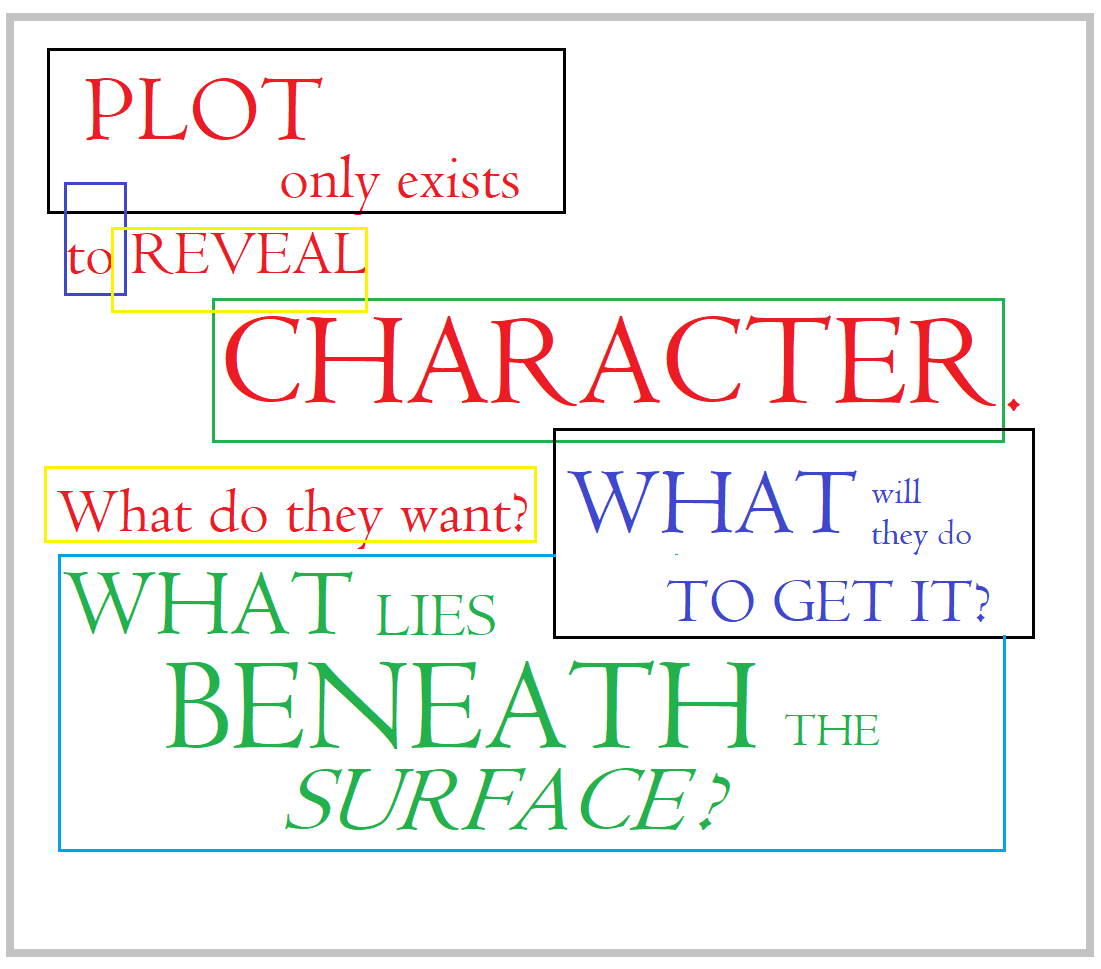

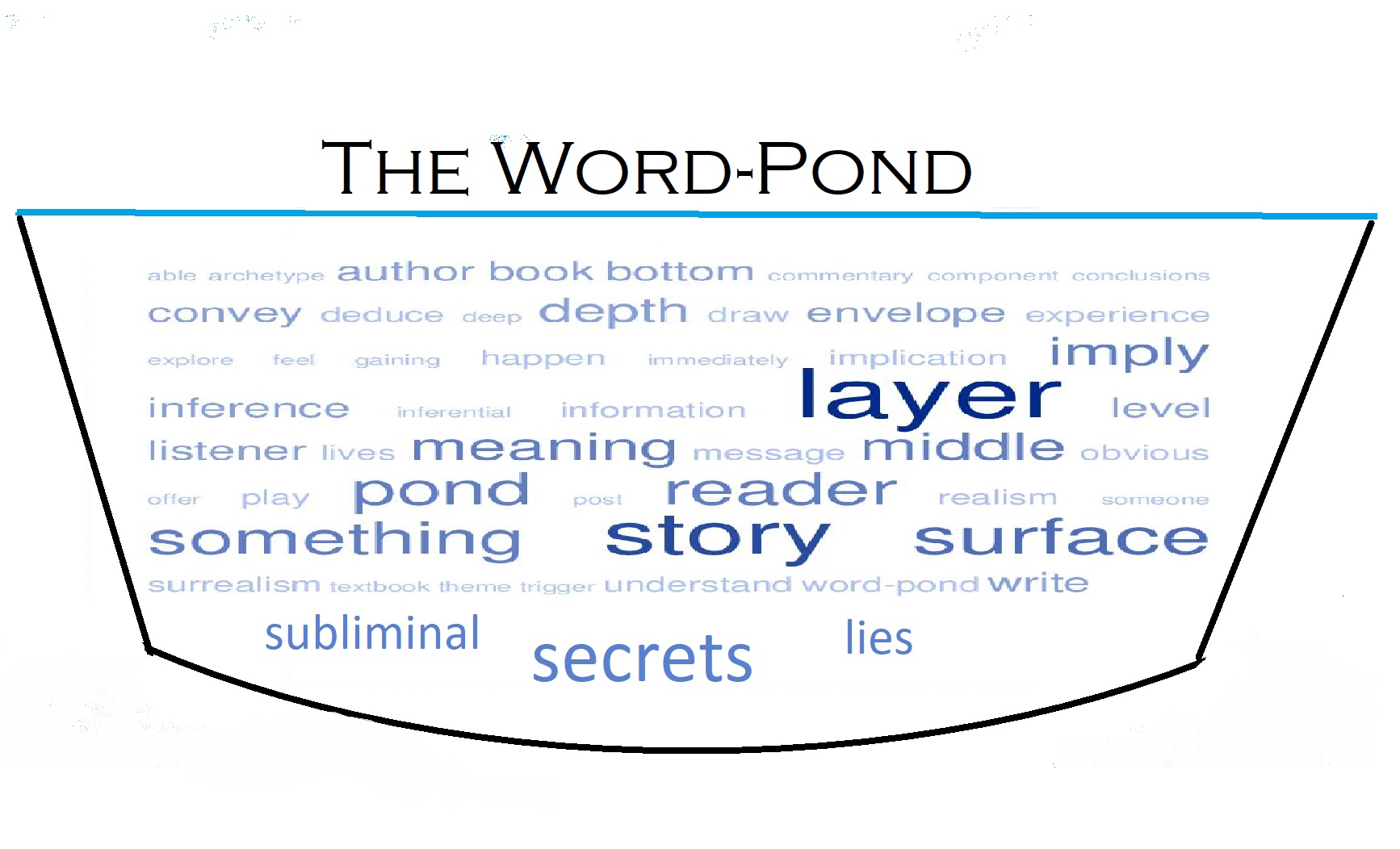

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Emotion is the experience of contrasts, of transitioning from the negative to the positive and back again. Mood, atmosphere, and emotion are part of the inferential layer of a story, part of the subtext. When an author has done their job well, the reader experiences the emotional transitions as the characters do. It is our job to make those transitions feel personal.

The atmosphere of a story is long-term. Atmosphere is the aspect of mood that is conveyed by the setting as well as the general emotional state of the characters.

The mood of a story is also long-term, but it is a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

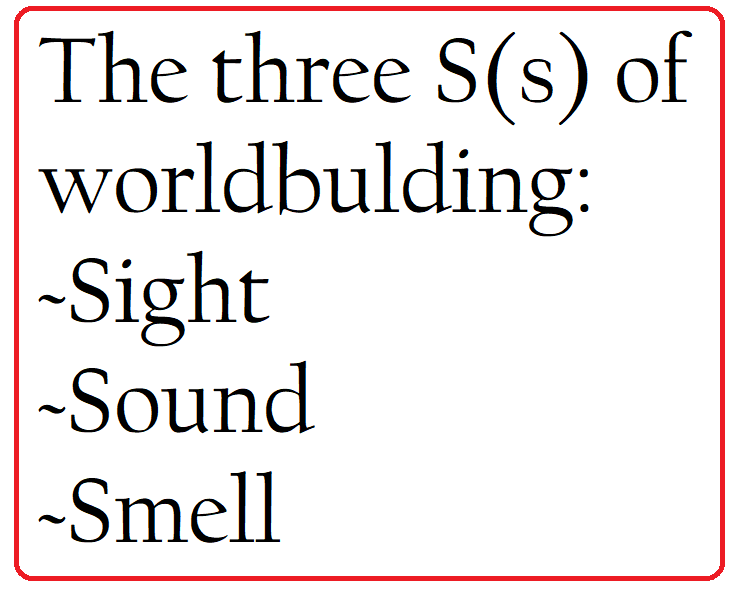

Scene framing is the order in which we stage the people and the visual objects we include in a scene, as well as the sequence of scenes along the plot arc. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere and contributes to the subtext. We choose the furnishings, sounds, and odors that are the visual necessities for that scene, and we place the scenes in a logical, sequential order.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

Barren landscapes and low windswept hills feel cold and dark to me. The word gothic in a novel’s description tells me it will be a dark, moody piece set in a stark, desolate environment. A cold, barren landscape, constant dampness, and continually gray skies set a somber tone to the background of the scene.

A setting like that underscores each of the main characters’ personal problems and evokes a general atmosphere of gloom.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

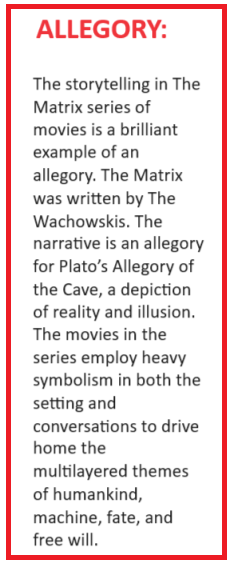

What tools in our writer’s toolbox are effective in conveying an atmosphere and a specific mood? Once we have chosen an underlying theme, it’s time to apply allegory and symbolism – two devices that are similar but different. The difference between them is how they are presented.

- Allegory is a moral lesson in the form of a story, heavy with symbolism.

- Symbolism is a literary device that uses one thing throughout the narrative (perhaps shadows) to represent something else (grief).

What are some examples? Cyberpunk, as a subgenre of science fiction, is exceedingly atmosphere-driven. It is heavily symbolic in worldbuilding and often allegorical in the narrative. We see many features of the classic 18th and 19th-century Sturm und Drang literary themes but set in a dystopian society. The deities that humankind must battle are technology and industry. Corporate uber-giants are the gods whose knowledge mere mortals desire and whom they seek to replace.

The setting and worldbuilding in cyberpunk work together to convey a gothic atmosphere, an overall feeling that is dark and disturbing. This is reflected in the subtext, which explores the dark nature of interpersonal relationships and the often criminal behaviors our characters engage in for survival.

No matter what genre we write in, we can use the setting to hint at what is to come. We can give clues by how we show the atmosphere with the inclusion of colors, scents, and ambient sounds. We choose our words carefully as they determine how the visuals are shown.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

Sunshine, green foliage, blue skies, and birdsong go a long way toward lifting my spirits, so when I read a scene that is set in that kind of environment, the mood of the narrative feels lighter to me.

Worldbuilding can feel complicated when we are trying to convey subtext, mood, and atmosphere but the reader won’t be aware of the complexities. All they will know is how strongly the protagonist and her story affected them and how much they loved that novel.

Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies.

Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies. We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government.

We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government. Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions.

Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions.

Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress.

Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress. In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment.

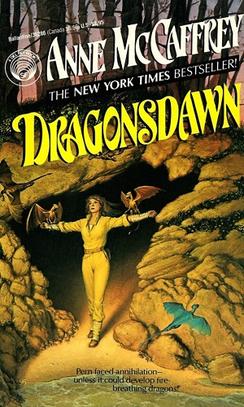

In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment. The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants.

The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants. The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted.

The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured.

Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured. This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.

This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground. Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.  These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story:

These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story: This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level.

This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level. As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere

As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere  However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc.

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc. So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world?

So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world? Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

Power structures are the hierarchies encompassing the leaders and the people with the power. Government is an overall system of restraint and control among selected members of a group. Think of it as a pyramid, a few at the top governing a wide base of citizens.

Power structures are the hierarchies encompassing the leaders and the people with the power. Government is an overall system of restraint and control among selected members of a group. Think of it as a pyramid, a few at the top governing a wide base of citizens. The same sort of God complex occurs among academicians and scientists. Some people are prone to excess when presented with the opportunity to become all-powerful.

The same sort of God complex occurs among academicians and scientists. Some people are prone to excess when presented with the opportunity to become all-powerful. Fantasy is and always has been my favorite genre. I became a fan when I first read the Hobbit at the age of nine. I have read countless works written by people who understood how to construct a plot and set it in a believable world. These classics trained me to notice contradictions in what I read, whether in a magic system or elsewhere in a book.

Fantasy is and always has been my favorite genre. I became a fan when I first read the Hobbit at the age of nine. I have read countless works written by people who understood how to construct a plot and set it in a believable world. These classics trained me to notice contradictions in what I read, whether in a magic system or elsewhere in a book. I can suspend my disbelief when magic is only possible if certain conditions have been met. The most believable magic occurs when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can do.

I can suspend my disbelief when magic is only possible if certain conditions have been met. The most believable magic occurs when the author creates a system that regulates what the characters can do. Superpowers are both science and something that may seem like magic, but they are not. Think Spiderman. His abilities are conferred on him by a scientific experiment that goes wrong.

Superpowers are both science and something that may seem like magic, but they are not. Think Spiderman. His abilities are conferred on him by a scientific experiment that goes wrong. While an ordinary life is comforting to those of us who simply long for peace and stability in our daily lives, we read for adventure. The story must take an average person, someone who could be your friend, into an extraordinary future.

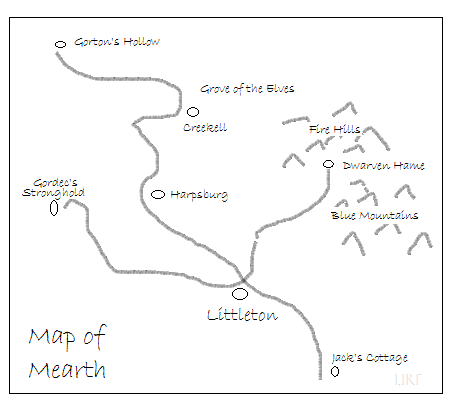

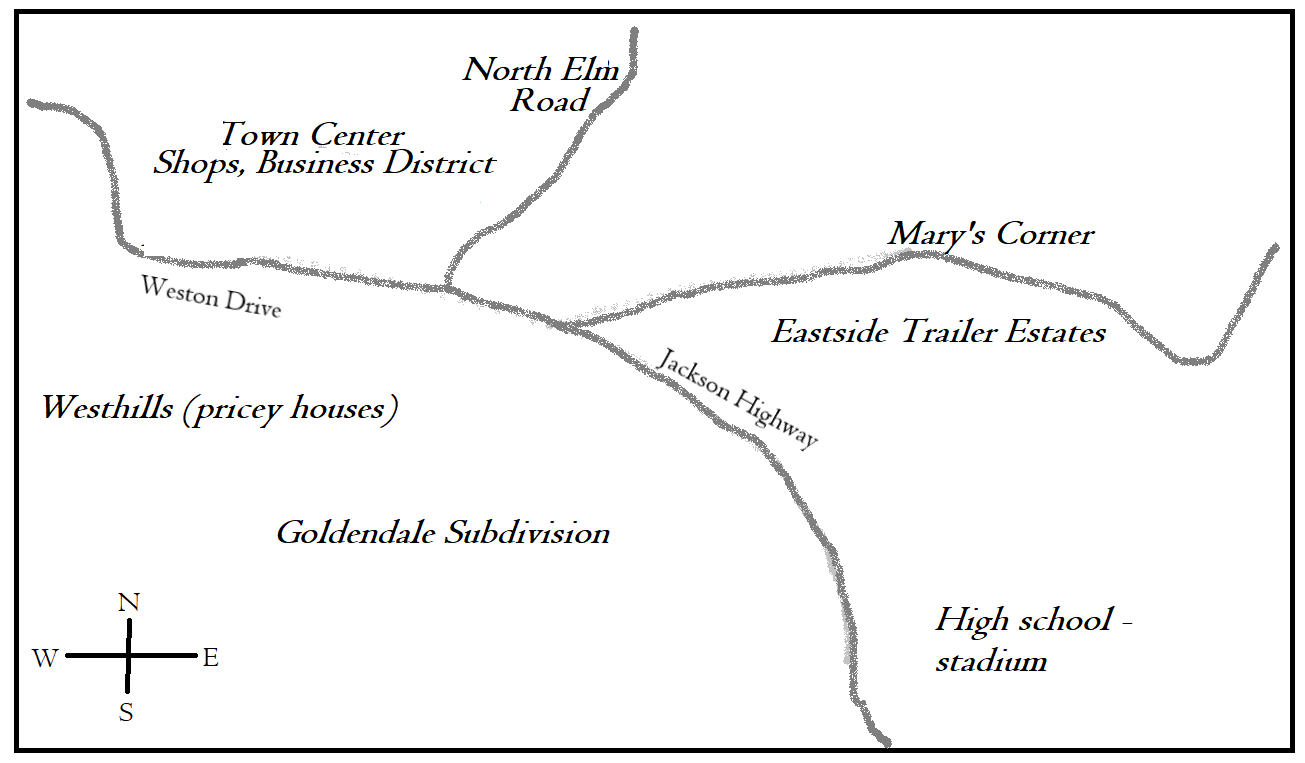

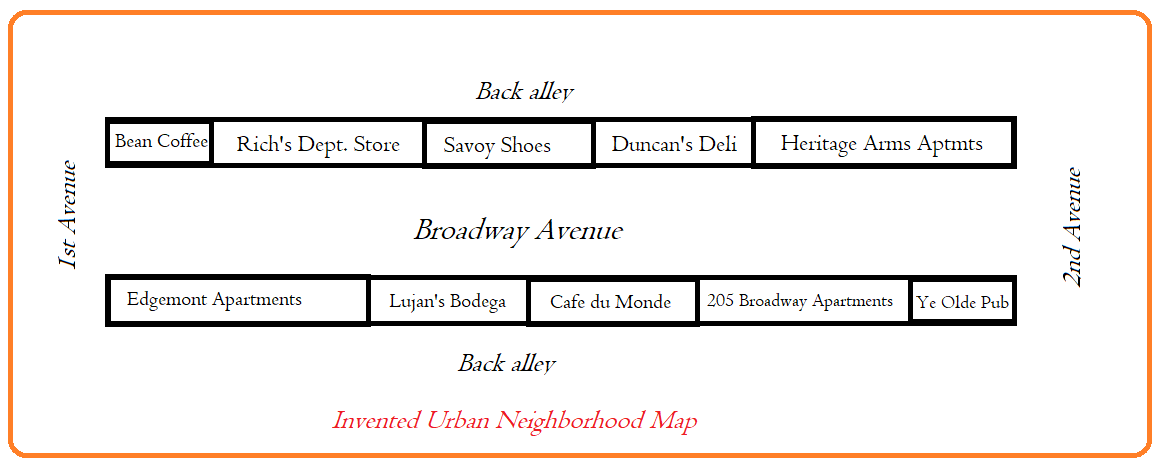

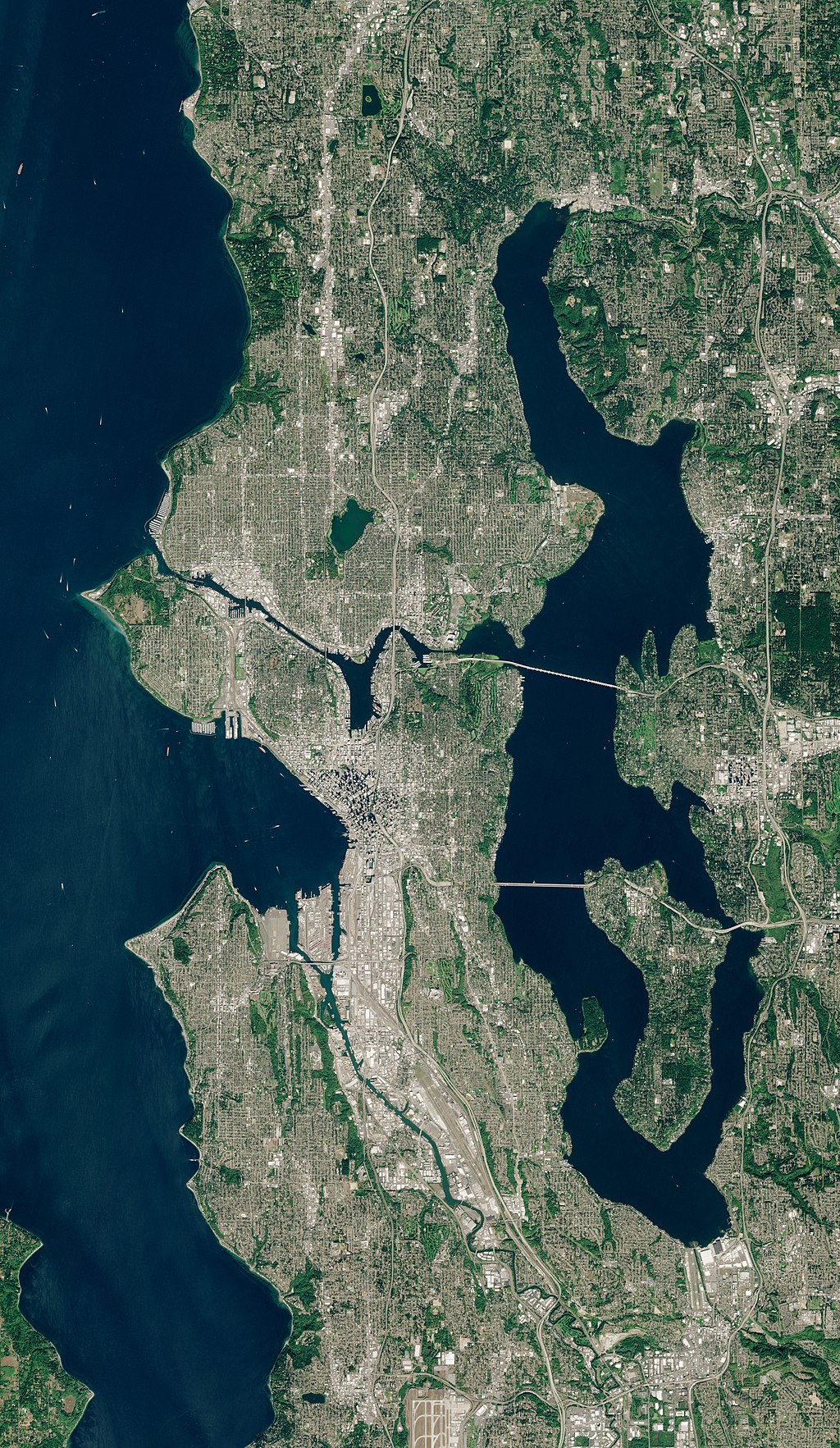

While an ordinary life is comforting to those of us who simply long for peace and stability in our daily lives, we read for adventure. The story must take an average person, someone who could be your friend, into an extraordinary future. Unfortunately, maps have fallen out of favor thanks to satellite technology and the GPS in our cell phones. Many people don’t know how to read a map.

Unfortunately, maps have fallen out of favor thanks to satellite technology and the GPS in our cell phones. Many people don’t know how to read a map.

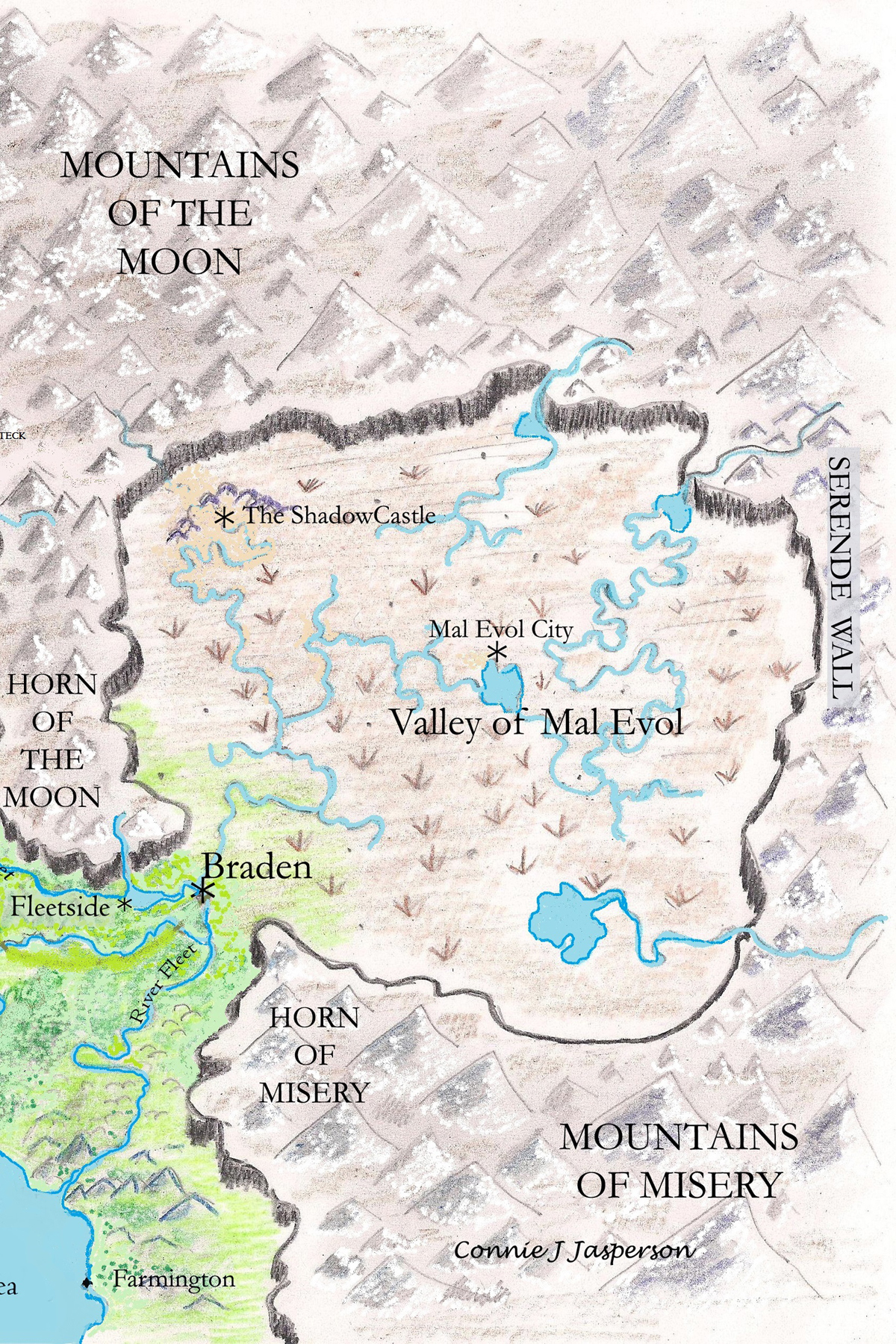

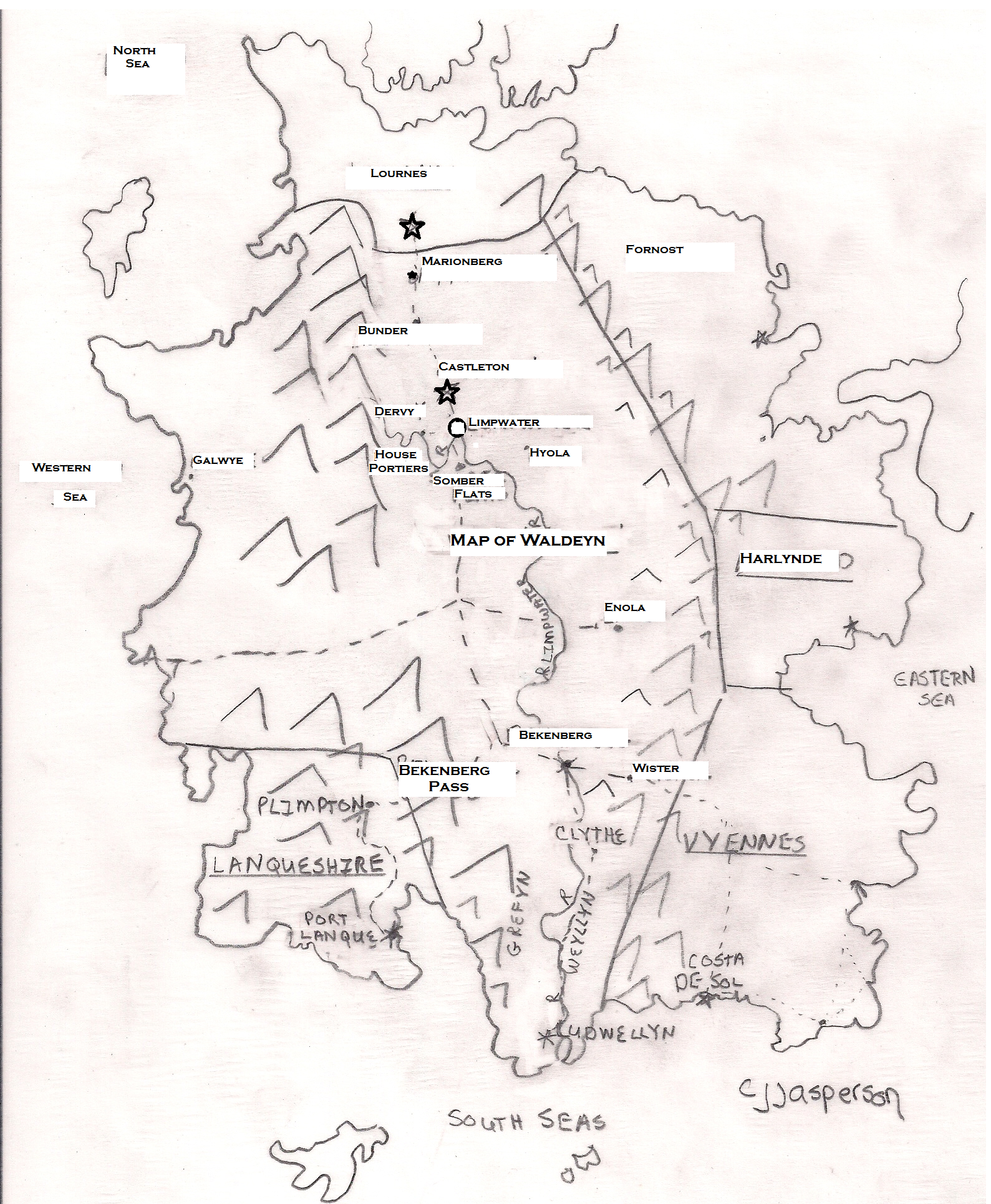

If you are designing a fantasy world, you only need a pencil-drawn map. Place north at the top, east to the right, south to the bottom, and west to the left. Those are called

If you are designing a fantasy world, you only need a pencil-drawn map. Place north at the top, east to the right, south to the bottom, and west to the left. Those are called  Use a pencil, so you can easily note whatever changes during revisions. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Lay it out like a standard map with north at the top, east on the right, south at the bottom, and west on the left.

Use a pencil, so you can easily note whatever changes during revisions. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Lay it out like a standard map with north at the top, east on the right, south at the bottom, and west on the left. Many towns are situated on rivers. Water rarely flows uphill. While it may do so if pushed by the force of wave action or siphoning, water is a slave to gravity and chooses to flow downhill. When making your map, locate rivers between mountains and hills.

Many towns are situated on rivers. Water rarely flows uphill. While it may do so if pushed by the force of wave action or siphoning, water is a slave to gravity and chooses to flow downhill. When making your map, locate rivers between mountains and hills. Maybe you aren’t artistic but will want a nice map later. In that case, a little scribbled map will enable a map artist to provide you with a beautiful and accurate product. An artist can give you a map containing the information readers need to enjoy your book.

Maybe you aren’t artistic but will want a nice map later. In that case, a little scribbled map will enable a map artist to provide you with a beautiful and accurate product. An artist can give you a map containing the information readers need to enjoy your book. In my part of the world, the native forest trees I see in the world around me are mostly Douglas firs, western red cedars, hemlocks, big-leaf maples, alders, cottonwood, and ash. Because I am familiar with them, these are the trees I visualize when I set a story in a forest.

In my part of the world, the native forest trees I see in the world around me are mostly Douglas firs, western red cedars, hemlocks, big-leaf maples, alders, cottonwood, and ash. Because I am familiar with them, these are the trees I visualize when I set a story in a forest.

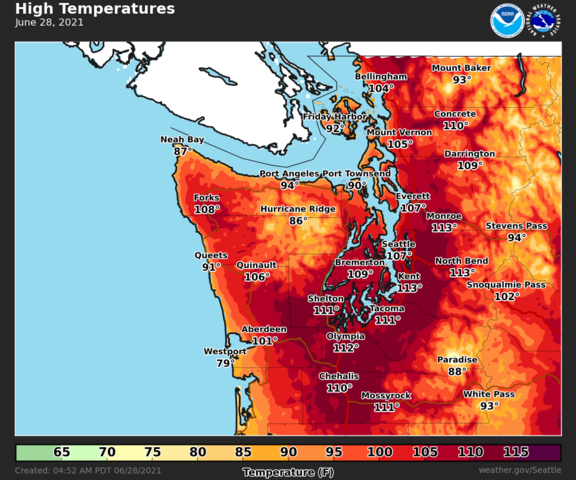

We know from bitter experience that weather affects the food we produce and influences what is available in grocery stores. Abnormal heat waves across temperate states, category 4 hurricanes along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico, and category 4 tornadoes down the center of the US and Canada, and even deep freezes in Texas and the deep south have been our lot in the last five years.

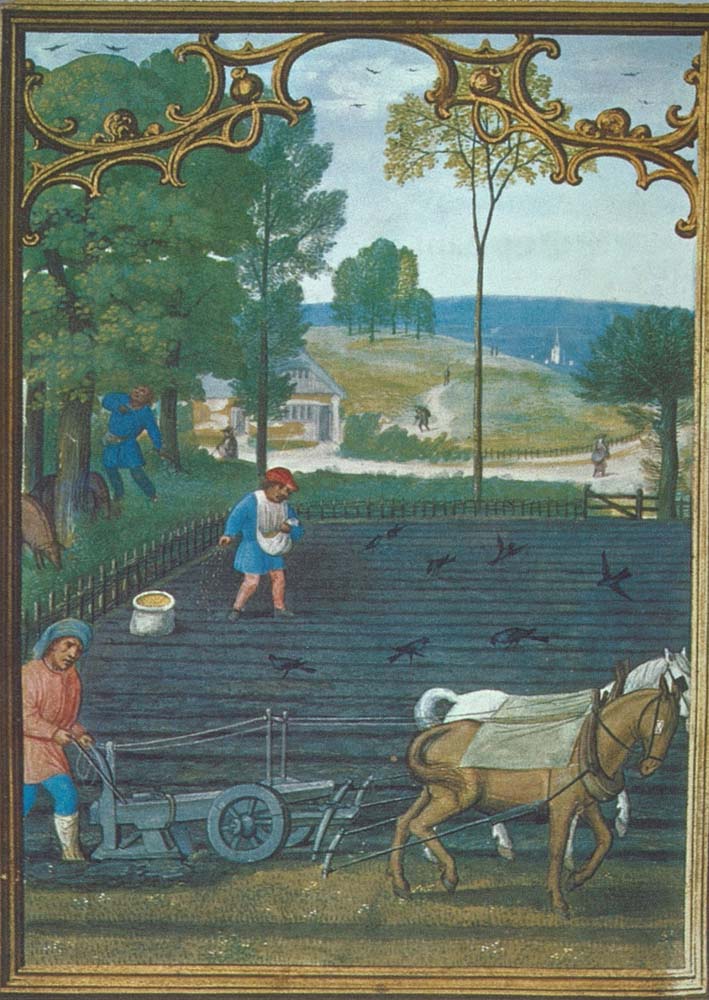

We know from bitter experience that weather affects the food we produce and influences what is available in grocery stores. Abnormal heat waves across temperate states, category 4 hurricanes along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico, and category 4 tornadoes down the center of the US and Canada, and even deep freezes in Texas and the deep south have been our lot in the last five years. Once you have decided your historical era, terrain, and overall climate, research similar areas of the real world to see how weather affects their approach to agriculture and animal husbandry. Look into the past to discover ancient agricultural methods to see how low-tech cultures fed their large populations:

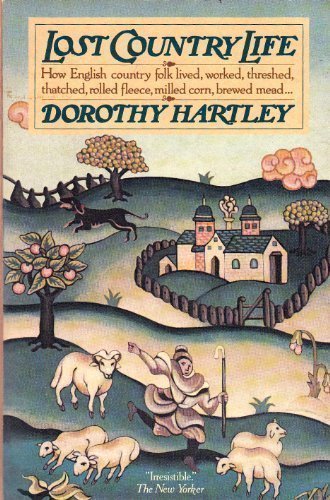

Once you have decided your historical era, terrain, and overall climate, research similar areas of the real world to see how weather affects their approach to agriculture and animal husbandry. Look into the past to discover ancient agricultural methods to see how low-tech cultures fed their large populations: Also, if your story is set in a particular era, how plentiful was food at that time? Famines occurring all across Europe and Asia over the last two-thousand years are well documented. Egyptian, Incan, and Mayan history is also fairly well documented so do the research.

Also, if your story is set in a particular era, how plentiful was food at that time? Famines occurring all across Europe and Asia over the last two-thousand years are well documented. Egyptian, Incan, and Mayan history is also fairly well documented so do the research. We have witnessed monumental changes since the turn of the millennium. We know California teeters on the edge of disaster, that a water shortage threatens the lives of millions, as well as one of the largest agriculture industries in the US.

We have witnessed monumental changes since the turn of the millennium. We know California teeters on the edge of disaster, that a water shortage threatens the lives of millions, as well as one of the largest agriculture industries in the US. Several years ago, I read a fantasy book where the author clearly spent many hours on the food of her fantasy world and the various animals. She gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture.

Several years ago, I read a fantasy book where the author clearly spent many hours on the food of her fantasy world and the various animals. She gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep. Most of the meat we served in our home was raised on his family’s communal farm. Our chickens and rabbits roamed their yard and had good lives, and our family’s herd of twenty sheep was managed using simple, old-style farming methods.

As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep. Most of the meat we served in our home was raised on his family’s communal farm. Our chickens and rabbits roamed their yard and had good lives, and our family’s herd of twenty sheep was managed using simple, old-style farming methods.

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. In

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. In