Today we’re continuing to explore character creation and the dark energy the villain of a piece brings to a story.

In his book, The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, Christopher Vogler discusses how the villain of a piece represents the shadow. The antagonist provides the momentum of the dark side, and their influence on the protagonist and the narrative should be profound.

In his book, The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, Christopher Vogler discusses how the villain of a piece represents the shadow. The antagonist provides the momentum of the dark side, and their influence on the protagonist and the narrative should be profound.

The shadow character serves several purposes.

- He/she/it is usually the main antagonist and represents darkness(evil) against which light (good) is shown more clearly.

- The shadow, whether a person, place, or thing, provides the roadblocks, the reason the protagonist must struggle.

The shadow lives within us all, and our heroes must also struggle with it. The most obvious example of this in pop culture is that of “Batman.”

About the original concept of Batman, via Wikipedia:

Batman is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in the 27th issue of the comic book Detective Comics on March 30, 1939. In the DC Universe continuity, Batman is the alias of Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American playboy, philanthropist, and industrialist who resides in Gotham City. Batman’s origin story features him swearing vengeance against criminals after witnessing the murder of his parents Thomas and Martha as a child, a vendetta tempered with the ideal of justice. He trains himself physically and intellectually, crafts a bat-inspired persona, and monitors the Gotham streets at night. Kane, Finger, and other creators accompanied Batman with supporting characters, including his sidekicks Robin and Batgirl; allies Alfred Pennyworth, James Gordon, and Catwoman; and foes such as the Penguin, the Riddler, Two-Face, and his archenemy, the Joker. [1]

Bruce Wayne is a flawed character. He is both a generous benefactor of many charities and a vigilante with little or no remorse for his actions. As Batman, he is a hero, a defender of the weak and defenseless. Much of what makes his story compelling is how he justifies indulging his darker side.

The story of Batman is complex, which is why so many movies have emerged exploring his story. We sit in theaters and applaud Batman’s dark side because it’s confined to taking on criminals.

The evil in a narrative is not always represented by a person. Sometimes war is the villain. Hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, wildfires—nature has a pantheon of calamities for us to overcome and no end of stories that emerge from such events.

True heroes don’t necessarily wear capes, and the evils they fight against are often disasters of epic proportions. Ordinary people can become heroes when faced with disasters of any sort.

Consider the true-life events of April 11 through the 17th, 1970. Via Wikipedia:

Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted after an oxygen tank in the service module (SM) failed two days into the mission. The crew instead looped around the Moon and returned safely to Earth on April 17. The mission was commanded by Jim Lovell, with Jack Swigert as command module (CM) pilot and Fred Haise as Lunar Module (LM) pilot. Swigert was a late replacement for Ken Mattingly, who was grounded after exposure to rubella. [2]

The villain in that epic space adventure was mechanical failure. The heroic efforts of the ground crew to brainstorm ways to get the astronauts home is one of the most powerful stories of the 20th century. We were glued to the television, watching as remedies for each disaster were devised, celebrating as the crew made their way home safely.

The villains we write into our stories represent humanity’s darker side, whether they are a person, a mechanical failure, a dangerous animal, or a natural disaster. They bring ethical and moral quandaries to the story, raising questions of morality, dilemmas we should examine more closely.

When the protagonist must face and overcome the shadow on a profoundly personal level, they are placed in true danger. Which way will they go? This is where my characters have agency, and they sometimes surprise me. They may unknowingly offer up their souls if they stray from the light.

Every character has a different personality and should respond to each event differently. The freedom you allow the protagonist and antagonist to steer the events is crucial for them to emerge as real to the reader.

Sometimes my characters make their own choices. Other times, they go along as I, their creator, have planned for them. Ultimately, they do things their own way and with their own style.

Our fictional heroes must recognize and confront the darkness within themselves. As they do so, the reader also faces it. The hero must choose their own path—will they fight to uphold the light? Will they walk in that gray area between? Bruce Wayne is a good example of one who walks the gray area.

The reader forms opinions and makes choices too, and these subliminal ideas sometimes challenge their ethics.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Batman,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Batman&oldid=1135964072 (accessed January 30, 2023).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Apollo 13,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Apollo_13&oldid=1133889788 (accessed January 30, 2023).

Image: Batman, drawn by Jim Lee for the cover of Batman: Hush. Created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger. DC Comics; 15794th edition (December 6, 2011) (Fair Use) Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Batman&oldid=1135964072 (accessed January 30, 2023).

Image: Apollo 13 Lift off, Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Apollo 13 liftoff-KSC-70PC-160HR.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Apollo_13_liftoff-KSC-70PC-160HR.jpg&oldid=560250836 (accessed January 30, 2023). Public Domain.

Authors make readers when they do in-person book signings. We have the chance to connect with potential readers on a personal level, and they might buy a paper book. If we are personable and friendly, they might tell their friends how much they liked meeting us. Those friends will buy eBooks. (We hope!)

Authors make readers when they do in-person book signings. We have the chance to connect with potential readers on a personal level, and they might buy a paper book. If we are personable and friendly, they might tell their friends how much they liked meeting us. Those friends will buy eBooks. (We hope!)

She also wrote the brilliant, hilarious standalone novel,

She also wrote the brilliant, hilarious standalone novel,  About Ellen King Rice:

About Ellen King Rice:

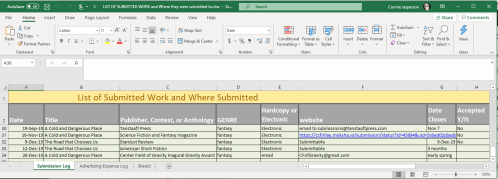

A new year has begun, and open calls for spring and summer contests and anthologies will start appearing in various forums that I frequent. Finding places to submit your work can be challenging, but here are links to two groups on Facebook where publishers post open calls for short stories.

A new year has begun, and open calls for spring and summer contests and anthologies will start appearing in various forums that I frequent. Finding places to submit your work can be challenging, but here are links to two groups on Facebook where publishers post open calls for short stories.

My problem is this: all my stories want to grow longer than 1,000 words. It requires weeks of effort to get my work to fit within that parameter. So, I often write practice stories, limiting myself to telling the whole story in 1000 words or less. These practice shorts serve several purposes:

My problem is this: all my stories want to grow longer than 1,000 words. It requires weeks of effort to get my work to fit within that parameter. So, I often write practice stories, limiting myself to telling the whole story in 1000 words or less. These practice shorts serve several purposes:

As a poet, I find it far easier to tell a story in 100 words than in 1,000. That 100-word story is called a

As a poet, I find it far easier to tell a story in 100 words than in 1,000. That 100-word story is called a  That way, you won’t be left wondering how to attend a conference and still cover your household bills.

That way, you won’t be left wondering how to attend a conference and still cover your household bills. For me, revisions begin with the second draft and sometimes involve radical changes to the storyline or character arcs. I may take a manuscript through many drafts before finally getting the story right.

For me, revisions begin with the second draft and sometimes involve radical changes to the storyline or character arcs. I may take a manuscript through many drafts before finally getting the story right. NEVER DELETE months of work. Don’t trash what could be the seeds of another novel. Save it in an outtakes file and use it later. I give the subfile a name like HA_outtakes_20Dec2022. That file name tells me the cut chapters were last changed on December 20, 2022.

NEVER DELETE months of work. Don’t trash what could be the seeds of another novel. Save it in an outtakes file and use it later. I give the subfile a name like HA_outtakes_20Dec2022. That file name tells me the cut chapters were last changed on December 20, 2022. Then, I give the second draft a new file name: Heavens_Altar_version_2, which becomes the version I work on out of the main file folder.

Then, I give the second draft a new file name: Heavens_Altar_version_2, which becomes the version I work on out of the main file folder. Either way, the characters will be profoundly changed from who they thought they were on page one, becoming who they are when the final sentence is written. The character arc is formed by their experiences.

Either way, the characters will be profoundly changed from who they thought they were on page one, becoming who they are when the final sentence is written. The character arc is formed by their experiences. True inspiration is not an everlasting firehose of ideas. Sometimes there are dry spells. If you take another look at the work you have cut and saved in an outtakes file, you might see it with fresh eyes. You might see the seeds of a different story, and the fire for writing will be reignited.

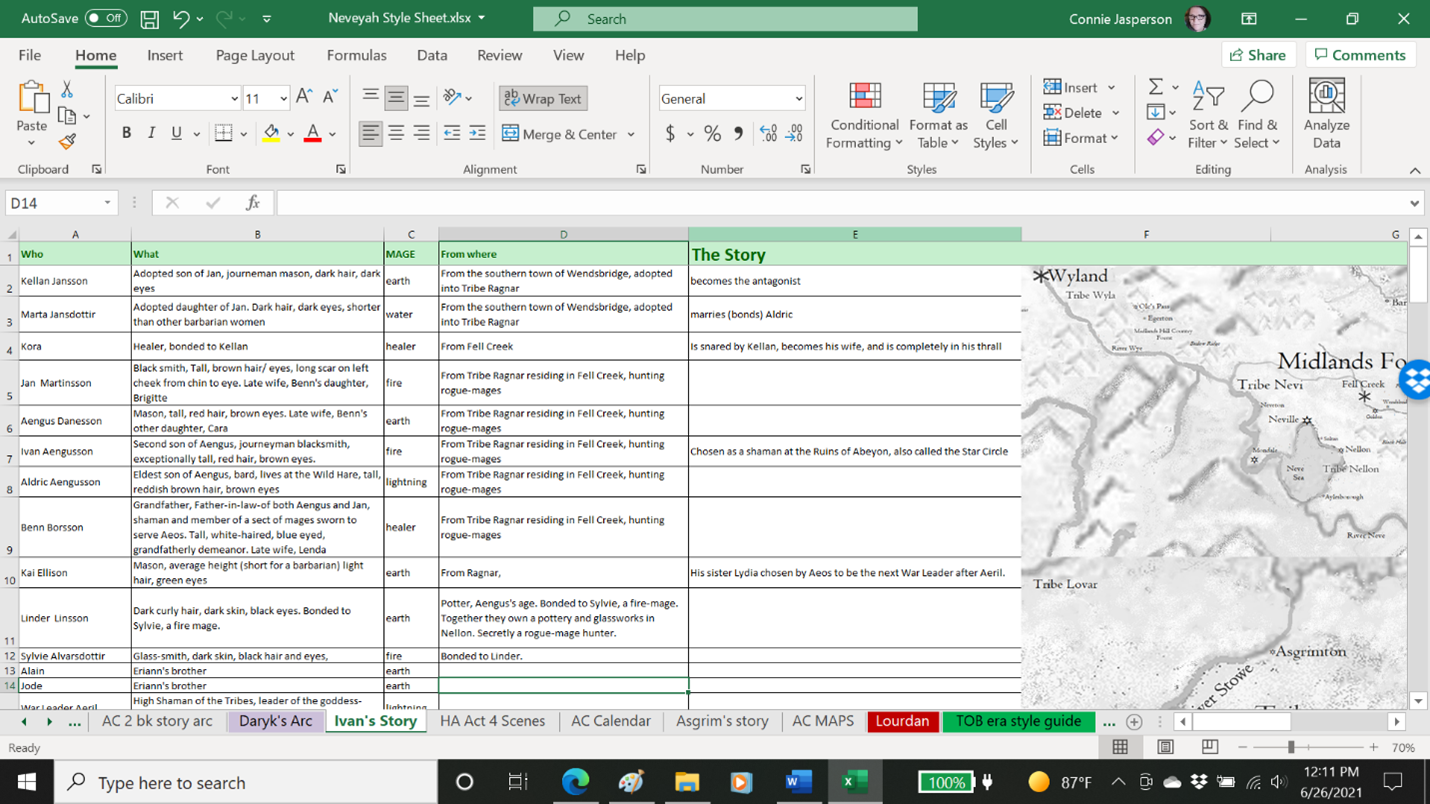

True inspiration is not an everlasting firehose of ideas. Sometimes there are dry spells. If you take another look at the work you have cut and saved in an outtakes file, you might see it with fresh eyes. You might see the seeds of a different story, and the fire for writing will be reignited. When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet.

When a manuscript comes across their desk, editors and publishers create a list of names, places, created words, and other things that may be repeated and pertain only to that manuscript. This is called a stylesheet. For short stories, the stylesheet will probably be a Word document. I have written them out by hand on occasion. You can create them in Google Sheets or Docs, which is free.

For short stories, the stylesheet will probably be a Word document. I have written them out by hand on occasion. You can create them in Google Sheets or Docs, which is free. Page Two: The projected story arc will be on page two of the workbook. I list each chapter by the events that need to be resolved at various points in the manuscript.

Page Two: The projected story arc will be on page two of the workbook. I list each chapter by the events that need to be resolved at various points in the manuscript. We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. We will probably deviate some from the original outline. Usually, for me, the major events will remain as they were plotted in advance, even though side themes will evolve. The outline keeps me on track with length and ensures the action doesn’t stall.

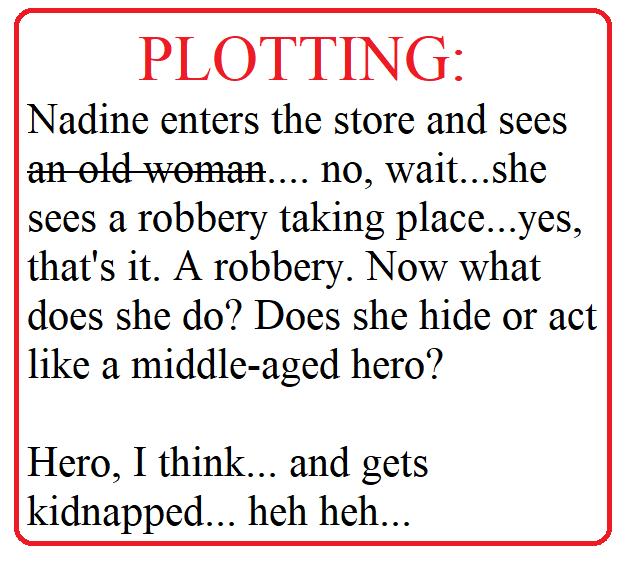

We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. We will probably deviate some from the original outline. Usually, for me, the major events will remain as they were plotted in advance, even though side themes will evolve. The outline keeps me on track with length and ensures the action doesn’t stall. The plot usually evolves as I write each event and connect the dots. In one instance, it was completely changed. The original plot didn’t work at all, so drastic measures had to be taken.

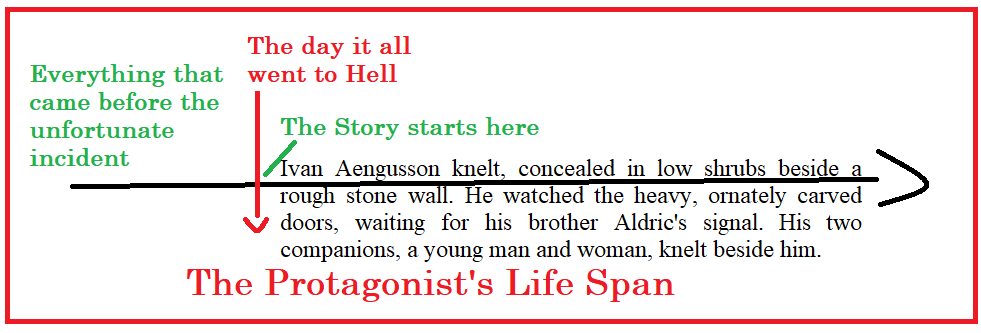

The plot usually evolves as I write each event and connect the dots. In one instance, it was completely changed. The original plot didn’t work at all, so drastic measures had to be taken. Today, we will pinpoint the moment in our protagonist(s) life where the story starts. We’re locating the point where this particular memoir, poem, novel, or short story begins.

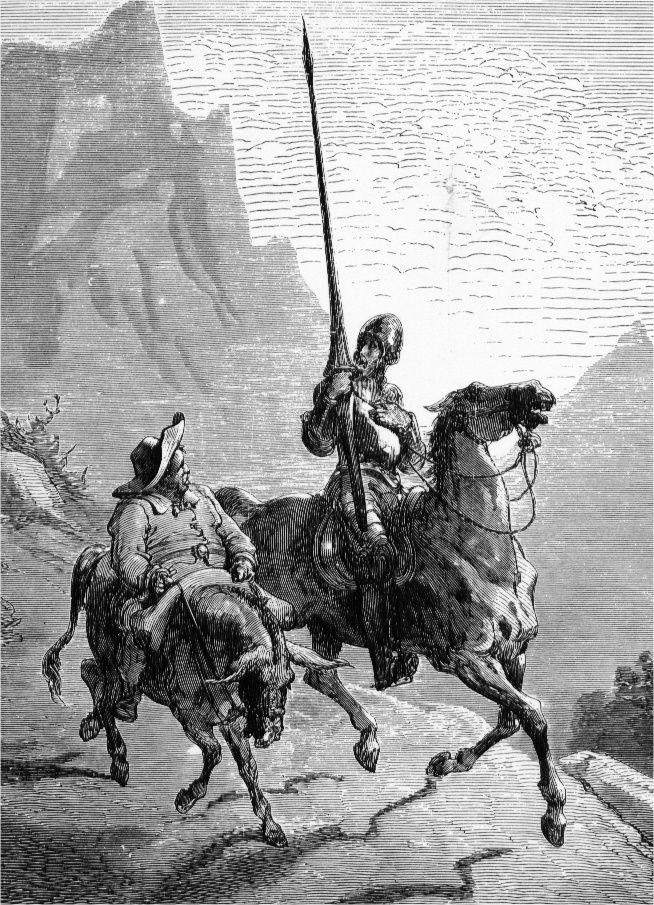

Today, we will pinpoint the moment in our protagonist(s) life where the story starts. We’re locating the point where this particular memoir, poem, novel, or short story begins. Setting: Venice in the year 1430.The weather is unseasonably cold. A bard is concealed amongst the filth and shadows in a dark, narrow alley. Sebastian hides from the soldiers of a prince he has unwisely humiliated in a comic song.

Setting: Venice in the year 1430.The weather is unseasonably cold. A bard is concealed amongst the filth and shadows in a dark, narrow alley. Sebastian hides from the soldiers of a prince he has unwisely humiliated in a comic song.

Post two

Post two

Marco arrives at the inn. The innkeeper mentions Klaus was there, but now he’s gone. Marco sees his barge is still there, and the deckhands don’t know where he is. He goes to the gatehouse where Dinah is supposed to be on duty and immediately knows something is wrong. He fears Klaus has gotten to her, and instinct tells him to go to the Temple.

Marco arrives at the inn. The innkeeper mentions Klaus was there, but now he’s gone. Marco sees his barge is still there, and the deckhands don’t know where he is. He goes to the gatehouse where Dinah is supposed to be on duty and immediately knows something is wrong. He fears Klaus has gotten to her, and instinct tells him to go to the Temple. In real life, people live happily, but no one really lives deliriously happy ever after. But that’s another story and a different genre.

In real life, people live happily, but no one really lives deliriously happy ever after. But that’s another story and a different genre. Now we’re going to design the conflict by creating a skeleton, a series of guideposts to write to. I write fantasy, but every story is the same, no matter the set dressing: Protagonist A needs something desperately, and Antagonist B stands in their way.

Now we’re going to design the conflict by creating a skeleton, a series of guideposts to write to. I write fantasy, but every story is the same, no matter the set dressing: Protagonist A needs something desperately, and Antagonist B stands in their way. Where does our soldier’s story begin? We open the story by introducing our characters, showing them in their everyday world, and then we kick into gear with the occurrence of the “inciting incident,” which is the first plot point. That might be their arrival at their first camp in the Ardennes region.

Where does our soldier’s story begin? We open the story by introducing our characters, showing them in their everyday world, and then we kick into gear with the occurrence of the “inciting incident,” which is the first plot point. That might be their arrival at their first camp in the Ardennes region.

One thing that I do is make notes that help limit my tendency toward heavy-handed foreshadowing. I try to keep it brief, but what will be enough of a hint, and where should it go?

One thing that I do is make notes that help limit my tendency toward heavy-handed foreshadowing. I try to keep it brief, but what will be enough of a hint, and where should it go?

So, for the two final weeks of November and the first two weeks of December, we will be firing up the Starship Hydrangea (our hydrangea-blue Kia Soul) and driving 30 miles a day to and from the clinic. This will happen four out of five days a week, barring snow.

So, for the two final weeks of November and the first two weeks of December, we will be firing up the Starship Hydrangea (our hydrangea-blue Kia Soul) and driving 30 miles a day to and from the clinic. This will happen four out of five days a week, barring snow. I have no problem getting the first draft done with the aid of a pot of hot, black tea and a simple outline to keep me on track. All that’s required is for me to sit down for an hour or two each morning and write a minimum of 1667 words per day.

I have no problem getting the first draft done with the aid of a pot of hot, black tea and a simple outline to keep me on track. All that’s required is for me to sit down for an hour or two each morning and write a minimum of 1667 words per day. The real work begins after November. After writing most of a first draft, many people will realize they enjoy writing. Like me, they’ll be inspired to learn more about the craft. They discover that writing isn’t about getting a particular number of words written by a specific date, although that goal was a catalyst, the thing that got them moving.

The real work begins after November. After writing most of a first draft, many people will realize they enjoy writing. Like me, they’ll be inspired to learn more about the craft. They discover that writing isn’t about getting a particular number of words written by a specific date, although that goal was a catalyst, the thing that got them moving. A good way to educate yourself is to attend seminars. By meeting and talking with other authors in various stages of their careers and learning from the pros, we develop the skills needed to write stories a reader will enjoy.

A good way to educate yourself is to attend seminars. By meeting and talking with other authors in various stages of their careers and learning from the pros, we develop the skills needed to write stories a reader will enjoy.