Authors talk a lot about motivation, often speaking in general terms. In a writing group, if a fellow member is stuck, we will ask them what their characters want most and what they’re willing to do to obtain it.

That question is a good place to start, but it is only the surface layer of the pond.

That question is a good place to start, but it is only the surface layer of the pond.

- Motivation is sometimes defined as the overall quest.

- Motives are more intimate, secrets held closely by the characters.

I like to use a watershed scene from the book The Fellowship of the Ring, as an example of this. If you have only seen the movie, you haven’t seen the real story as Tolkien himself told it. Let’s look at the Council of Elrond.

This scene is the only one where most of the characters are gathered in one place. They are there to decide who will mount the quest to destroy the One Ring. The scene is set in Rivendell, Elrond’s remote mountain citadel.

Each character attending the council has arrived there on a separate errand. Each has different hopes for what will ultimately come from the meeting. Despite their various agendas, each is ultimately concerned with the Ring of Power. Each wants to protect their people from Sauron’s depredations if he were to regain possession of it.

This scene serves several functions:

Information/Revelation: The Council of Elrond conveys information to both the protagonists and readers.

It is a conversation scene, driven by the fact that each person in the meeting has knowledge the others need. Conversations are good when they deploy necessary information. Remember, plot points are driven by the characters who have critical knowledge.

It is a conversation scene, driven by the fact that each person in the meeting has knowledge the others need. Conversations are good when they deploy necessary information. Remember, plot points are driven by the characters who have critical knowledge.

The fact that some characters are working with limited information creates tension. At the Council of Elrond, many things are discussed, and the whole story of the One Ring is explained, with each character offering a new piece of the puzzle. The reader and the characters receive the information simultaneously at this point in the novel.

Every person in the Fellowship is motivated by the need to keep the One Ring from falling into Sauron’s hands. This is the acknowledged reason for their accompanying Frodo and is the core plot point around which the story unfolds.

Yet, everyone attending the council has an unspoken agenda that will affect Frodo’s mission. Ultimately, those secret motives are the undoing of some and the making of others.

Samwise is a loyal friend who refuses to leave Frodo’s side. Fear that Frodo will need him forces him to insist on being included.

Pippin and Merry have similar but different reasons—they don’t want to be left out if Frodo and Sam are going on an adventure. Their motives are simple at the outset but become more complicated as their stories diverge and unfold.

Boromir desires the Ring for what he believes is a noble purpose and intends to take it to Minas Tirith. He knows the power of the Ring and believes that if he possesses it, Gondor will return to its former glory and be safe forever. He will rule the world with a just hand.

Thus, Boromir’s true motive is a quest for personal power. His agenda kicks into place at Amon Hen.

The Council of Elrond serves several functions:

Information/Revelation: The Council of Elrond conveys information to both the protagonists and readers. It is a conversation scene, driven by the fact that each person in the meeting has knowledge the others need. Plot points are propelled by the characters who have critical knowledge. Again, limited information creates tension.

Information/Revelation: The Council of Elrond conveys information to both the protagonists and readers. It is a conversation scene, driven by the fact that each person in the meeting has knowledge the others need. Plot points are propelled by the characters who have critical knowledge. Again, limited information creates tension.

Interracial bigotry emerges, and a confrontation ensues. At the Council of Elrond, long-simmering racial tensions between Gimli the Dwarf and Legolas the Elf surface. Each is confrontational by nature, and it’s doubtful whether they will agree to work together.

Sometimes, a verbal confrontation gives the reader the context needed to understand why the action occurred. The conversation and reaction give the scene context, which is critical. A scene that is all action can be confusing if it has no context.

Other conflicts are explored, and heated exchanges occur between Aragorn and Boromir.

Pacing: We have action/confrontation in this vignette, followed by conversation and the characters’ reactions.

Negotiation: What concessions will be required to achieve the final goal? These concessions must be negotiated.

First, Tom Bombadil is mentioned as one who could safely take the Ring to Mordor as it has no power over him. Gandalf feels he would simply lose the Ring or give it away because Tom lives in his own reality and doesn’t see Sauron as a problem.

Bilbo volunteers, but he is too old and frail. Others offer, but none are accepted as good candidates for the job of ring-bearer for one reason or another.

Each justification Gandalf and Elrond offer for why these characters are wrong for the job deploys a tidbit of information the reader needs.

Turning Point: After much discussion, revelations, and bitter arguments, Frodo declares that he will go to Mordor and dispose of the Ring, giving up his chance to live his remaining life in the comfort and safety of Rivendell. Sam emerges from his hiding place and demands to be allowed to accompany Frodo. This is the turning point of the story.

The movie portrays this scene differently, with Pip and Merry hiding in the shadows. Also, in the book, the decision about who will accompany Frodo, other than Sam, is not made for several days, while the movie shortens it to one day.

The movie portrays this scene differently, with Pip and Merry hiding in the shadows. Also, in the book, the decision about who will accompany Frodo, other than Sam, is not made for several days, while the movie shortens it to one day.

The fundamental laws of physics, the rules that govern the universe, are in force here: Everything in that chapter happens for a reason. There is always a causative factor.

- Without a cause, there is no effect.

- Cause is motivation.

- Effect becomes cause, which becomes motivation.

- Motivation is a chain reaction of cause and effect, which becomes the story.

And it’s all traceable back to the character’s desire to do or have something.

Characters that feel too shallow sometimes lack sufficient personal motivations. The reader can’t see why they would buy into the larger quest.

If we have supplied each character with a secret backstory, those hinted-at motives can sometimes push the story into newer, more original waters.

And, isn’t that what we readers are looking for? We read because we are searching for a story that feels new, one that offers us a fresh view of the world through the characters’ eyes.

Credits and Attributions:

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Rings, Theatrical release poster, New Line Cinema, © 2001, all rights reserved. Wikipedia contributors, “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Lord_of_the_Rings:_The_Fellowship_of_the_Ring&oldid=1186704895 (accessed December 3, 2023). Fair Use.

We who write fantasy invent people and give them lives in invented worlds. Their stories involve them doing invented things. Unfortunately, there are times when we realize we have written ourselves into a corner, and there is no graceful way out.

We who write fantasy invent people and give them lives in invented worlds. Their stories involve them doing invented things. Unfortunately, there are times when we realize we have written ourselves into a corner, and there is no graceful way out. In 2019, I had accomplished many important things with the 3 months of work I had cut from that novel. The world was solidly built, so the first part of the rewrite went quickly. The characters were firmly in my head, so their interactions made sense in the new context.

In 2019, I had accomplished many important things with the 3 months of work I had cut from that novel. The world was solidly built, so the first part of the rewrite went quickly. The characters were firmly in my head, so their interactions made sense in the new context. So, in 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so the best choice is to break it into two novels.

So, in 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so the best choice is to break it into two novels. And a “passel” of short stories and novellas.

And a “passel” of short stories and novellas. I think of

I think of  When I can’t write anymore, I eat chocolate and read trashy romance novels about vampires.

When I can’t write anymore, I eat chocolate and read trashy romance novels about vampires. I need to spend several days visualizing the goal, picturing each event, and mind-wandering on paper until I have concrete scenes. I need to write a few paragraphs that will become the final chapters.

I need to spend several days visualizing the goal, picturing each event, and mind-wandering on paper until I have concrete scenes. I need to write a few paragraphs that will become the final chapters. My heroes and villains all see themselves as the stars and winners in this fantasy rumble. They intend to prevail at any cost. What is the final hurdle, and what will they lose in the process? Is the price physical suffering or emotional? Or both?

My heroes and villains all see themselves as the stars and winners in this fantasy rumble. They intend to prevail at any cost. What is the final hurdle, and what will they lose in the process? Is the price physical suffering or emotional? Or both? My mental rambling is accomplishing something. My characters are all getting their acts together. They are finding ways to resolve the conflict and are ready to commence the fourth act, where they will embark on the final battle.

My mental rambling is accomplishing something. My characters are all getting their acts together. They are finding ways to resolve the conflict and are ready to commence the fourth act, where they will embark on the final battle. I still had no idea there was a wider community of writers in my area, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have felt worthy of gate-crashing one of their meetings.

I still had no idea there was a wider community of writers in my area, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have felt worthy of gate-crashing one of their meetings. The next book I bought was in 2002:

The next book I bought was in 2002:  Finishing off the resources from the official NaNoWriMo store is Grant Falkner’s handbook,

Finishing off the resources from the official NaNoWriMo store is Grant Falkner’s handbook,  Damn Fine Story

Damn Fine Story Many local libraries offer a service where one can submit a question and have it answered by email. If that isn’t an option and we’re feeling ambitious, you can check out eBooks on any subject.

Many local libraries offer a service where one can submit a question and have it answered by email. If that isn’t an option and we’re feeling ambitious, you can check out eBooks on any subject. Here is a link to the great Neil Gaiman’s absolutely wonderful, infinitely comforting, yet utterly challenging advice for writers:

Here is a link to the great Neil Gaiman’s absolutely wonderful, infinitely comforting, yet utterly challenging advice for writers:  In 2010, I gained a wonderful local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo. Nowadays, we meet weekly via Zoom, as some members are now living far away from Olympia. My fellow writers are a never-ending source of support and information about both the craft and the industry. We write in various genres and gladly help each other bring new books into the world. But more than that, we are good, close friends.

In 2010, I gained a wonderful local group through attending write-ins for NaNoWriMo. Nowadays, we meet weekly via Zoom, as some members are now living far away from Olympia. My fellow writers are a never-ending source of support and information about both the craft and the industry. We write in various genres and gladly help each other bring new books into the world. But more than that, we are good, close friends. Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level.

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they are fictionalized accounts. They detail an incident or event and talk about how the experience affected the author on a personal level. Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values.

Wallace went to the fair thinking it would be a boring event featuring farm animals, which might be beneath him. But it was his first official assignment for Harpers, and he didn’t want to screw it up. What he found there, the people he met, their various crafts, and how they loved their lives profoundly affected him, altering his view of himself and his values. Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights.

Literary magazines want well-written essays on a wide range of topics and life experiences presented with a fresh point of view. Some publications will pay well for first rights. Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language.

Don’t be afraid to write with a wide vocabulary, as people who read these publications have a broad command of language. If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business.

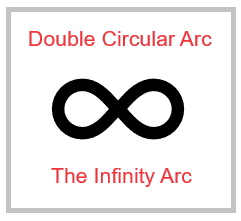

If the editor wants changes, they will make clear what they want you to do. Editors know what their intended audience wants. Trust that the editor knows their business. Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc.

Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc. In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events. At this point, our first protagonist knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people, which he does. There is more to his side of the story, of course. But this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story.

At this point, our first protagonist knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people, which he does. There is more to his side of the story, of course. But this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story. Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch).

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch). We all know the best stories have an arc of rising action flowing smoothly from scene to scene. Those changes are called transitions and are little connecting scenes. Conversations and indirect speech (thoughts, ruminations, contemplations) often make good transitions when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right.

We all know the best stories have an arc of rising action flowing smoothly from scene to scene. Those changes are called transitions and are little connecting scenes. Conversations and indirect speech (thoughts, ruminations, contemplations) often make good transitions when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. We know dialogue must have a purpose and move toward a conclusion of some sort. This means conversations or ruminations should provide a sense of moving the story forward. These are moments of regrouping and processing what has just occurred. Dialogue and introspection are also where the protagonist and the reader learn more about the mysterious backstory.

We know dialogue must have a purpose and move toward a conclusion of some sort. This means conversations or ruminations should provide a sense of moving the story forward. These are moments of regrouping and processing what has just occurred. Dialogue and introspection are also where the protagonist and the reader learn more about the mysterious backstory. So now that we know what must be conveyed and why, we find ourselves walking through the Minefield of Too Much Exposition.

So now that we know what must be conveyed and why, we find ourselves walking through the Minefield of Too Much Exposition. When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves to express what was happening inside them.

When I began writing seriously, I was in the habit of using italicized thoughts and characters talking to themselves to express what was happening inside them. If you aren’t careful, you can slip into “head-hopping,” which is incredibly confusing for the reader. First, you’re in one person’s thoughts, and then another—like watching a tennis match.

If you aren’t careful, you can slip into “head-hopping,” which is incredibly confusing for the reader. First, you’re in one person’s thoughts, and then another—like watching a tennis match. Crockpot soups are high on the menu here at Casa del Jasperson. I do most of the work for dinner in the morning and get it out of the way along with the other housework, and then I can write and whine about writing.

Crockpot soups are high on the menu here at Casa del Jasperson. I do most of the work for dinner in the morning and get it out of the way along with the other housework, and then I can write and whine about writing. The work inspired by a visual prompt often has nothing to do with the image. But it has everything to do with the nature of storytelling. The ability to explain the world through stories and allegory emerges strongly in artists of all mediums—painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, and dancers.

The work inspired by a visual prompt often has nothing to do with the image. But it has everything to do with the nature of storytelling. The ability to explain the world through stories and allegory emerges strongly in artists of all mediums—painters, sculptors, writers, musicians, and dancers. These jolly rogues have such vivid personalities that the viewer immediately feels a kinship. Who were they? Did they keep their day jobs? Or were they charming moochers living off the kindness of friends?

These jolly rogues have such vivid personalities that the viewer immediately feels a kinship. Who were they? Did they keep their day jobs? Or were they charming moochers living off the kindness of friends? And what other symbolism was incorporated in this painting that art patrons in the 17th century would know but we who view it through 21st-century eyes wouldn’t? Eelko Kappe’s article on this painting,

And what other symbolism was incorporated in this painting that art patrons in the 17th century would know but we who view it through 21st-century eyes wouldn’t? Eelko Kappe’s article on this painting,  The well of inspiration has gone dry.

The well of inspiration has gone dry. Arcs of action drive plots. Every reader knows this, and every writer tries to incorporate that knowledge into their work. Unfortunately, when I’m tired, random, disconnected events that have no value will seem like good ideas.

Arcs of action drive plots. Every reader knows this, and every writer tries to incorporate that knowledge into their work. Unfortunately, when I’m tired, random, disconnected events that have no value will seem like good ideas. As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come.

As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come.

On Monday, I had to drive to Seattle to take the hubby for a consult with a neurosurgeon. Getting to the doctor was fine. It was a matter of spending one hour sitting in traffic trying to leave Olympia and another hour of actually rolling forward once we made it past the Nisqually River. I had planned ahead for that, so we were on time. The upshot is no back surgery for him unless there is no other option, as Parkinson’s patients do very poorly after surgeries.

On Monday, I had to drive to Seattle to take the hubby for a consult with a neurosurgeon. Getting to the doctor was fine. It was a matter of spending one hour sitting in traffic trying to leave Olympia and another hour of actually rolling forward once we made it past the Nisqually River. I had planned ahead for that, so we were on time. The upshot is no back surgery for him unless there is no other option, as Parkinson’s patients do very poorly after surgeries. So, what am I writing today? I’m working on the second half of a novel I began writing seven years ago, so all the world-building and character creation has happened. The plot for this half is evolving. I know the ending, and over the next thirty days, my characters will take me from this high point in the middle, through several hurdles yet to be determined, to that final victory.

So, what am I writing today? I’m working on the second half of a novel I began writing seven years ago, so all the world-building and character creation has happened. The plot for this half is evolving. I know the ending, and over the next thirty days, my characters will take me from this high point in the middle, through several hurdles yet to be determined, to that final victory. I’m settling into the new office. In my old house, my ramshackle desk was in the Room of Shame, a jumbled mess of a storeroom. My new desk is not duct taped together and has the right amount of storage for what I need.

I’m settling into the new office. In my old house, my ramshackle desk was in the Room of Shame, a jumbled mess of a storeroom. My new desk is not duct taped together and has the right amount of storage for what I need. Today, the office/guestroom walls are barren, but I hope to have all the family pictures hung by the end of this week. The hide-a-bed sofa and side chair make a pleasant conversation area or guest room, whichever is needed. All I lack is my new desk chair, which is on its way here from Norway. (Yes, I splurged on a Stressless desk chair since I spend most of my time sitting in front of my computer.) It should be here in a week or two, and I can hardly wait as my current desk chair loses its appeal after an hour or so.

Today, the office/guestroom walls are barren, but I hope to have all the family pictures hung by the end of this week. The hide-a-bed sofa and side chair make a pleasant conversation area or guest room, whichever is needed. All I lack is my new desk chair, which is on its way here from Norway. (Yes, I splurged on a Stressless desk chair since I spend most of my time sitting in front of my computer.) It should be here in a week or two, and I can hardly wait as my current desk chair loses its appeal after an hour or so. What are some of my planned treats? Cranberry and walnut shortbread, for one thing. Shortbread is so easy and affordable to make that it always surprises me when people don’t. I have veganized all of my old traditional recipes, so everyone can sneak a treat now and then.

What are some of my planned treats? Cranberry and walnut shortbread, for one thing. Shortbread is so easy and affordable to make that it always surprises me when people don’t. I have veganized all of my old traditional recipes, so everyone can sneak a treat now and then.