Scope creep (aka project creep, requirement creep, or kitchen sink syndrome) in project management refers to ongoing changes and continuous (or uncontrolled) growth of a project. This can occur at any point after the project commences.

In writing, this happens when the narrative keeps expanding, and expanding, and expanding … and what was canon in chapter 4 is contradicted in chapter 44. The story grows as we write it.

In writing, this happens when the narrative keeps expanding, and expanding, and expanding … and what was canon in chapter 4 is contradicted in chapter 44. The story grows as we write it.

I love the name kitchen sink syndrome. It means we begin adding everything but the kitchen sink to the project—one of my fatal flaws. This becomes a problem when building science fiction and fantasy worlds because they emerge from our imaginations and grow and evolve with every new idea we have.

Scope creep is built into the early drafts. Readers remember the smallest details and use them to visualize the world they are reading about. They notice contradictions.

We fantasy and sci-fi authors can inadvertently build flaws into the geography as we lay the story down on paper and expand on scenes and interactions. This is why you need some idea of distances and how long it takes to travel using the common mode of transportation.

We don’t want to build contradictions into our narrative, but we all want a way to speed up the process of finishing the first draft. I find a small, hand-scribbled map is the best way to do this. I begin with the opening location.

Also, and this is important–when I get stuck and can’t think of what to write, creating a map helps jog things loose.

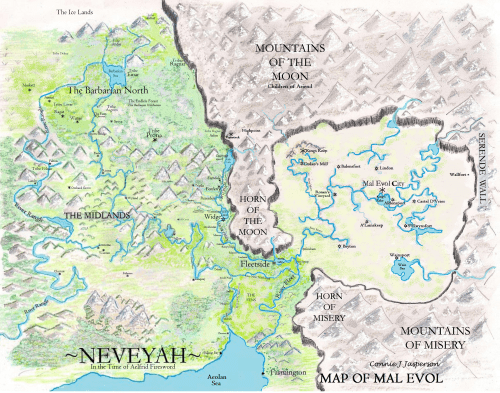

Much of my work takes place in the world of Neveyah. This alien environment is familiar to me because I based the plants and topography on the Pacific Northwest, where I live. Other than the Escarpment, the visible scar left behind by the Sundering of the Worlds, the plants and geography are directly pulled from Southern Puget Sound’s forested hills and the farmlands of Western Washington State.

Conversely, the Valley of Mal Evol is a reflection of the eastern half of our geographically divided state.

In 2008, when I first began writing in this world, I went to science to see how long it takes for an environment to recover from cataclysmic events. I took my information from the Channeled Scablands of Washington State, a two-hour drive from my home. This vast desert area is formed by the scars of a series of natural disasters occurring around 13,000 years ago.

From Wikipedia: The Cordilleran Ice Sheet dammed up Glacial Lake Missoula at the Purcell Trench Lobe. A series of floods occurring over the period of 18,000 to 13,000 years ago swept over the landscape when the ice dam broke. The eroded channels also show an anastomosing, or braided, appearance. [1]

But what if we’re writing a historical novel. No matter when or where your book is set, a certain amount of worldbuilding will be required. But even though your book may explore a real woman’s experiences, researched through newsreels, her diary, and the interviews you had with her just before her death at the age of 103, you are still writing a fantasy.

This is because, in reality, the world of any book exists only in three places: it begins in the author’s imagination, lands on the pages of the book, and then flows into the reader’s experience through the written word.

We can only view history through the stained glass of time. History, even recent events, assumes a mythical quality when we attempt to record it. Even a documentary movie that shows events filmed by the news camera may not be portrayed as it was truly experienced. The facts are filtered through the photographer’s eye and the historian’s pen.

Any story set in prehistorical times is a fantasy.

- Historical eras are those where we have written records.

- Any story set in a society without written records must be considered a fantasy. Although mythology, conjecture, and theorizing abound, few scientific facts exist until an archeological expedition can investigate any artifacts and ruins they left behind. And even then, there will be a certain literary license to the archaeologist’s conclusions.

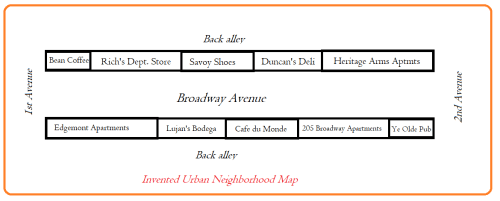

If you are setting your novel in a real-world city as it currently exists, make good use of Google Earth. Bookmark it now, even if you live in that town, as the maps you will generate will help you stay on track.

If you are writing a tale set in a fantasy or sci-fi setting, you are creating that world.

If you are writing a tale set in a fantasy or sci-fi setting, you are creating that world.

The first map of my world of Neveyah series was scribbled with a pencil on graph paper. Over time it evolved into a full-color relief map of the world as it exists in my mind.

I love maps. My own maps start out in a rudimentary form, just a way to keep my story straight. I use pencil and graph paper at this stage because:

- As the rough draft evolves, sometimes towns must be renamed.

- They may have to be moved to more logical places.

- Whole mountain ranges may have to be moved or reshaped so our characters encounter forests and savannas where they are supposed to be in the story.

What should go on a map? Truthfully, not a whole lot.

- Where your people are.

- Where the places they will go are in relation to their starting point (north, south, east, or west).

- Where the story ends.

Yep, that’s it unless you want to draw maps—my hobby. All you need for now is the jumping-off point and the essential places. When the mighty heroine leaves home with her trusty sword or phaser, she will always know where she is. She won’t inadvertently transport an entire town from the north to the south of that mountain range.

Original Map of Neveyah from 2008 ©Connie J. Jasperson

As your story evolves, you will add all the details as they occur to you and believe me—they will come. In the meantime, your map page will be ready and waiting for you to note the particulars. When you are spilling words, the details will emerge, and you will have towns, geological features, and names firmly in your mind.

What if you are only beginning to write your story? Why should you be worried about mapping it out now?

When traveling great distances, your characters may pass through villages on their way. Perhaps the environment will impede them, or better yet, create an obstacle that must be overcome. The map will grow and shrink as you add or delete places from it.

Suppose environmental or geographical obstacles are pertinent to the story. In that case, taking a moment to note their location on your map will be easy. This way, you won’t interrupt the momentum of your writing and won’t contradict yourself if your party must return the way they came.

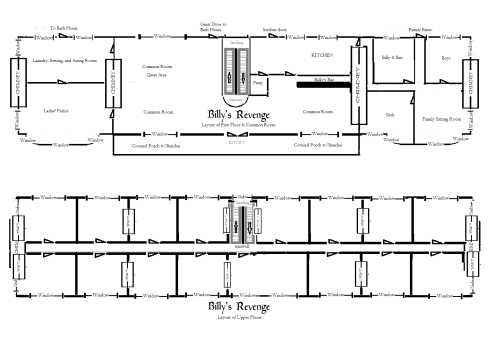

If your work is sci-fi, consider making a map of where the action happens, even though no one will see it but you. It could be a pencil-drawn floor plan of a space station/ship or a line drawing of part of an alien world. I drew the floorplan of the inn, Billy’s Revenge, for my reference as most of the novel Billy Ninefingers takes place there.

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Use a pencil to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. You want to know:

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Use a pencil to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. You want to know:

- Where your people are.

- Where the places they will go are in relation to their starting point (north, south, east, or west)

- Where the story ends

- Names of places and their proper spelling

Maybe you feel you aren’t artistic but know you’ll want a nice map later. Your scribbled map will enable a map artist to provide you with a beautiful and accurate product. You will have a map that contains the information needed for readers to enjoy your book.

Credits and Attributions:

Map of Neveyah © 2012 Connie J. Jasperson all rights reserved.

Floorplan of Billy’s Revenge © Connie J. Jasperson all rights reserved.

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Channeled Scablands,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Channeled_Scablands&oldid=963105167 (accessed June 4, 2023).

No matter the level of our education or the dialect we speak, we use these rules and don’t realize we are doing so.

No matter the level of our education or the dialect we speak, we use these rules and don’t realize we are doing so. Muddled phrasings often slip by when I revise my work because my mind sees the words as if they were in the correct order. This is the writer’s curse—the internal editor knows what should be there, and the eye skips over what we actually wrote.

Muddled phrasings often slip by when I revise my work because my mind sees the words as if they were in the correct order. This is the writer’s curse—the internal editor knows what should be there, and the eye skips over what we actually wrote. I adore mishmash words. They’re poetic and musical and roll off the tongue with a satisfying rhythm. Sadly, while I regularly bore my grandchildren with them, I hardly ever get to write them. Mishmash. Hip-hop.

I adore mishmash words. They’re poetic and musical and roll off the tongue with a satisfying rhythm. Sadly, while I regularly bore my grandchildren with them, I hardly ever get to write them. Mishmash. Hip-hop. “Ing” words are a terrible temptation to those of us raised on Tolkien. He was writing a century ago, but that style of lush prose has fallen out of fashion. We open the gate to all sorts of verbal mayhem when we lead off with an “ing” word at the front of a sentence.

“Ing” words are a terrible temptation to those of us raised on Tolkien. He was writing a century ago, but that style of lush prose has fallen out of fashion. We open the gate to all sorts of verbal mayhem when we lead off with an “ing” word at the front of a sentence. It’s been over ten years since I first started writing my series about the adventures of a professional monster hunter. With the release of

It’s been over ten years since I first started writing my series about the adventures of a professional monster hunter. With the release of  One of my most treasured experiences in writing The Adventures of Keltin Moore has been meeting the fantastic subject experts in the course of my research. I already mentioned panning for gold, but there have been so many more generous, enthusiastic people I’ve spoken to on subjects ranging from big game hunters to horse-pulled wagons. In particular, I feel blessed to have known Gordon and Nancy Frye. The Fryes are a fantastic wealth of historical information, particularly regarding the development and implementation of firearms over the centuries. If you ever read something in my stories and thought that something involving guns was particularly cool, you can probably thank the Fryes for contributing to it!

One of my most treasured experiences in writing The Adventures of Keltin Moore has been meeting the fantastic subject experts in the course of my research. I already mentioned panning for gold, but there have been so many more generous, enthusiastic people I’ve spoken to on subjects ranging from big game hunters to horse-pulled wagons. In particular, I feel blessed to have known Gordon and Nancy Frye. The Fryes are a fantastic wealth of historical information, particularly regarding the development and implementation of firearms over the centuries. If you ever read something in my stories and thought that something involving guns was particularly cool, you can probably thank the Fryes for contributing to it! Lindsay Schopfer is the award-winning author of The Adventures of Keltin Moore, a series of steampunk-flavored fantasy novels about a professional monster hunter. He also wrote the sci-fi survivalist novel Lost Under Two Moons and the fantasy short story collection Magic, Mystery and Mirth. Lindsay’s workshops and seminars on the craft of writing have been featured in a variety of Cons and writing conferences across the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

Lindsay Schopfer is the award-winning author of The Adventures of Keltin Moore, a series of steampunk-flavored fantasy novels about a professional monster hunter. He also wrote the sci-fi survivalist novel Lost Under Two Moons and the fantasy short story collection Magic, Mystery and Mirth. Lindsay’s workshops and seminars on the craft of writing have been featured in a variety of Cons and writing conferences across the Pacific Northwest and beyond. The movers came on Friday to take what furniture we could gracefully fit into the new apartment. They loaded the van far more quickly than I thought they would. The main hiccup in that day came in the form of the elevator in our building. We are in building C but must go in through the main lobby in building B, take the elevator to our floor, and cross to our building via the sky bridge. It’s a long trek.

The movers came on Friday to take what furniture we could gracefully fit into the new apartment. They loaded the van far more quickly than I thought they would. The main hiccup in that day came in the form of the elevator in our building. We are in building C but must go in through the main lobby in building B, take the elevator to our floor, and cross to our building via the sky bridge. It’s a long trek. Over the next week, we have to donate as much as possible to be reused, and the rest will be hauled away by the junk removal company. They will not only take the junk but also clean the garage floor. (!!!)

Over the next week, we have to donate as much as possible to be reused, and the rest will be hauled away by the junk removal company. They will not only take the junk but also clean the garage floor. (!!!) On the good side, it is easy to write here. I have been writing bits and bobs here and there on old unfinished manuscripts between bursts of unpacking, writing whenever I sit down to rest my back. It keeps me from fidgeting.

On the good side, it is easy to write here. I have been writing bits and bobs here and there on old unfinished manuscripts between bursts of unpacking, writing whenever I sit down to rest my back. It keeps me from fidgeting. In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world.

In literary terms, this uneven distribution of knowledge is called asymmetric information. We see this all the time in the corporate world. Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him.

Jared is hilarious, charming, naïve, a bit cocky, and completely unaware that he’s an arrogant jackass. He is a young man who is exceptionally good at everything and is happy to tell you about it. Jared has no clue that his boasting holds him back, as no one wants to work with him. When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility.

When I started writing this story, I had the core conflict: Jared’s misguided desire to be important. I had the surface quest: rescuing the kidnapped kid. I had the true quest: Jared learning to laugh at himself and developing a little humility. Calendar time is a layer of world-building. It sets the story in a particular era and shows the passage of time.

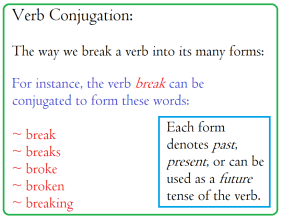

Calendar time is a layer of world-building. It sets the story in a particular era and shows the passage of time. Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.”

Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.” Every story is unique; some work best in the past tense, while others must be set in the present.

Every story is unique; some work best in the past tense, while others must be set in the present. If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia.

If I were writing a story starring me as the main character, I would open it in the year 2005 with a couple of empty-nesters buying a house in a bedroom community twenty miles south of Olympia. The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here.

The city center is isolated, twelve miles from the freeway and twenty miles away from every other town in the south county. If a fictional story were set in this town, it would feature the same political and religious schisms that divide the rest of our country. There are other tensions. Some families have been here for generations, and a few don’t appreciate the influx of low-paid state workers buying cookie-cutter tract homes (like mine) here. Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure.

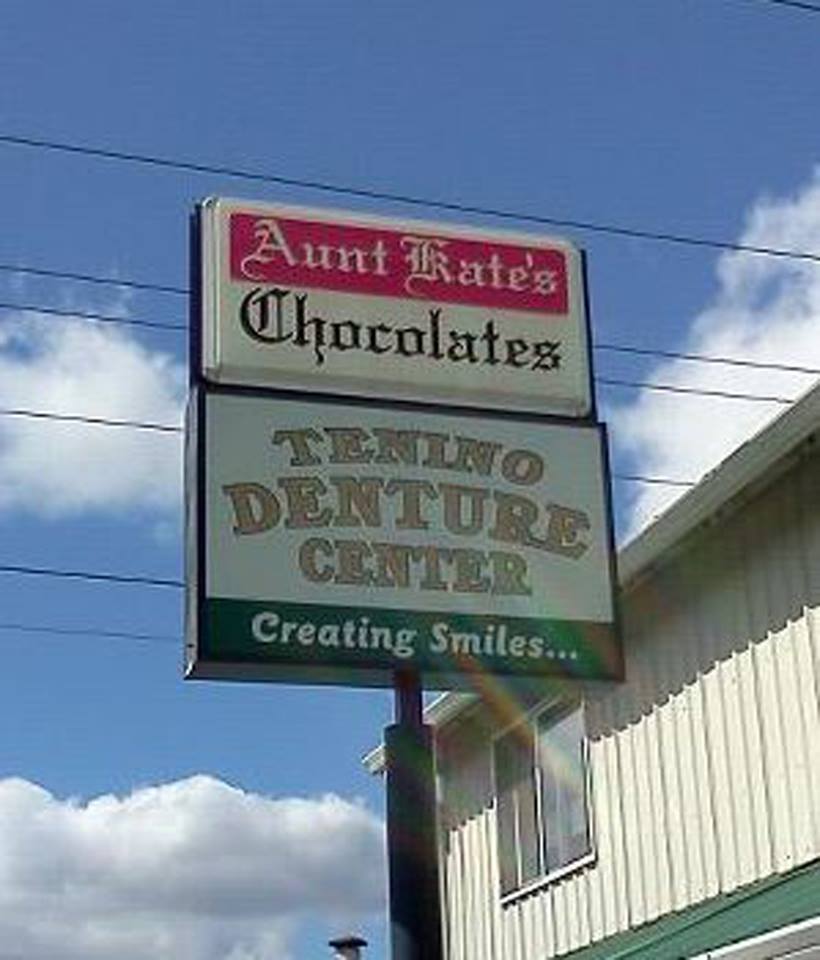

Two inches of rain fell the day we moved into our brand-new home in 2005, making moving our furniture into this house a misery. Our new house had no landscaping and rose from a sea of mud and rocks. With a lot of effort, we made a pleasant yard. When the housing bubble burst in 2008, many people on my side of the street lost their jobs, and some homes went into foreclosure. Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

Our main street, Sussex, passes through a historic district. The buildings are all built from sandstone quarried at the old quarries. Many of the old buildings are home to antique stores. The masonic lodge is made of Tenino sandstone.

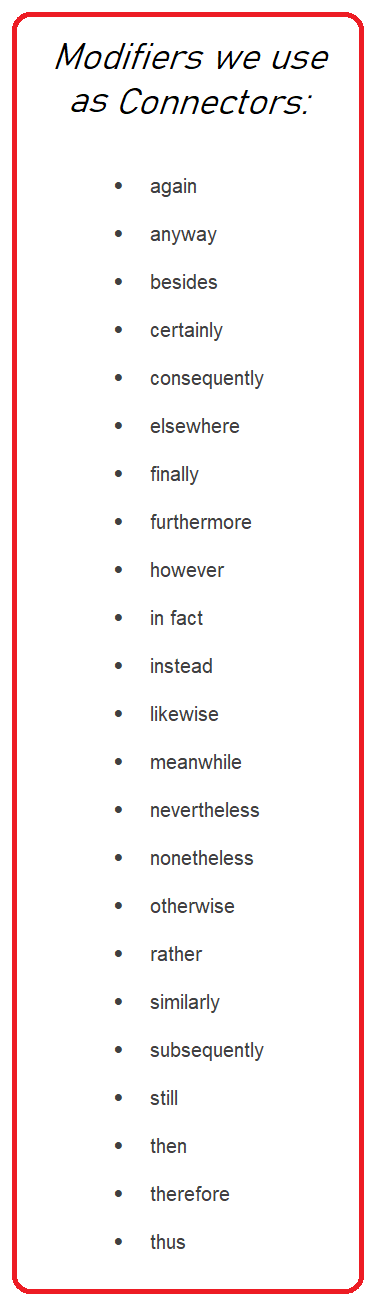

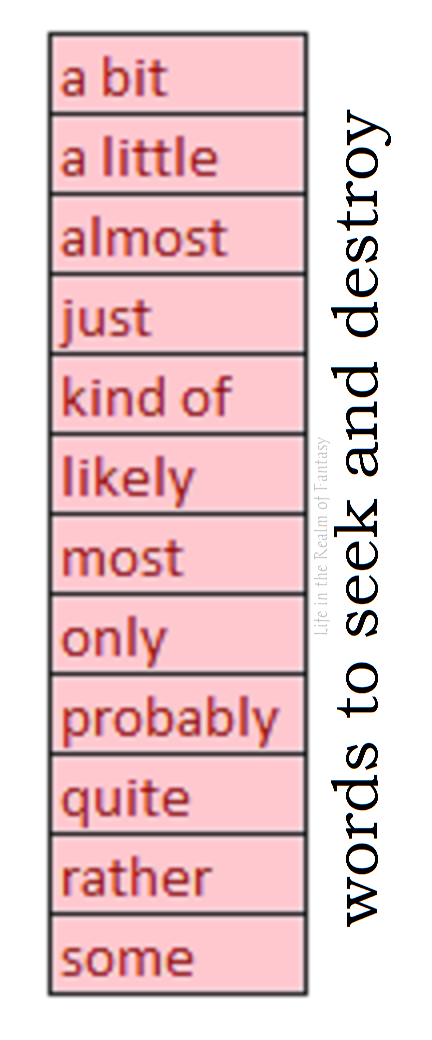

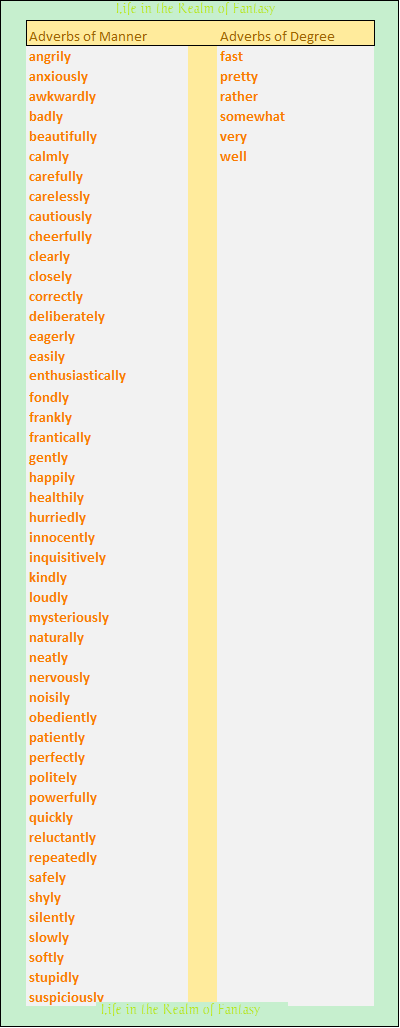

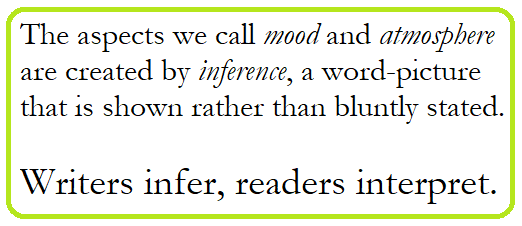

In writing, we add depth and contour to our prose by how we choose and use our words. We “paint” a scene using words to show what the point-of-view character is seeing or experiencing. Yes, we do need to use some modifiers and descriptors.

In writing, we add depth and contour to our prose by how we choose and use our words. We “paint” a scene using words to show what the point-of-view character is seeing or experiencing. Yes, we do need to use some modifiers and descriptors. One of the cautions those of us new to the craft frequently hear are criticisms about the number of modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) we habitually use. This can hurt, especially if we don’t understand what the members of our writing group are trying to tell us.

One of the cautions those of us new to the craft frequently hear are criticisms about the number of modifiers (adjectives and adverbs) we habitually use. This can hurt, especially if we don’t understand what the members of our writing group are trying to tell us. In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb-article-noun (burned the eyes). Lead with the action or noun, follow with a strong modifier, and the sentence conveys what is intended but isn’t weakened by the modifiers.

In the above sentence, the essential parts are structured this way: noun – verb (sunlight glared), adjective – noun (cold fire), verb – adjective – noun (cast no warmth), and finally, verb-article-noun (burned the eyes). Lead with the action or noun, follow with a strong modifier, and the sentence conveys what is intended but isn’t weakened by the modifiers.

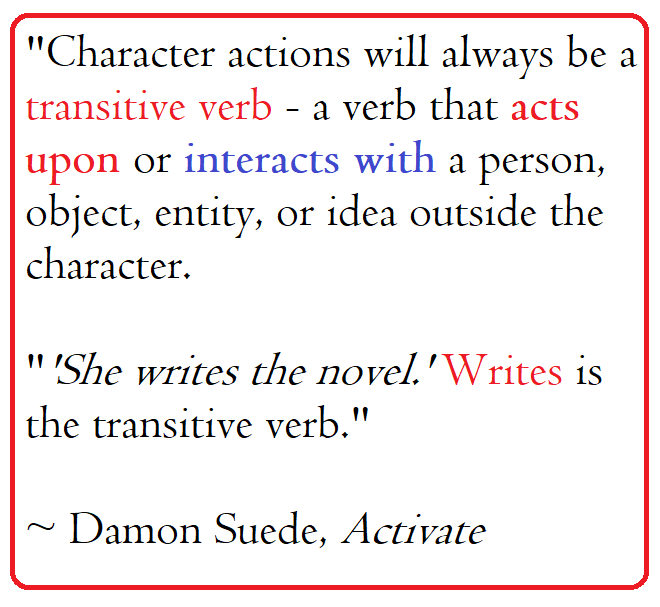

In his book,

In his book,  Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation.

Truthfully, I find detailed descriptions of facial expressions to be boring and sometimes off-putting. Every author armed with a little knowledge writes characters with curving lips, stretching lips, and lips doing many things over, and over, and over … with little variation. Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful.

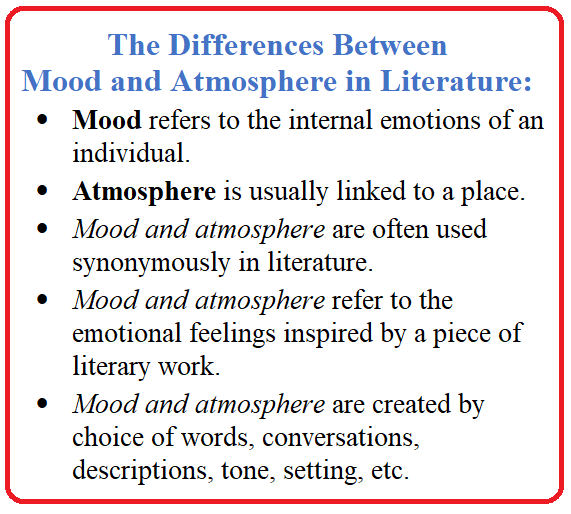

Simplicity has an impact, but I struggle to achieve balance. When looking for words with visceral and emotional power, consonants are your friend. Verbs that begin with consonants are powerful. Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story.

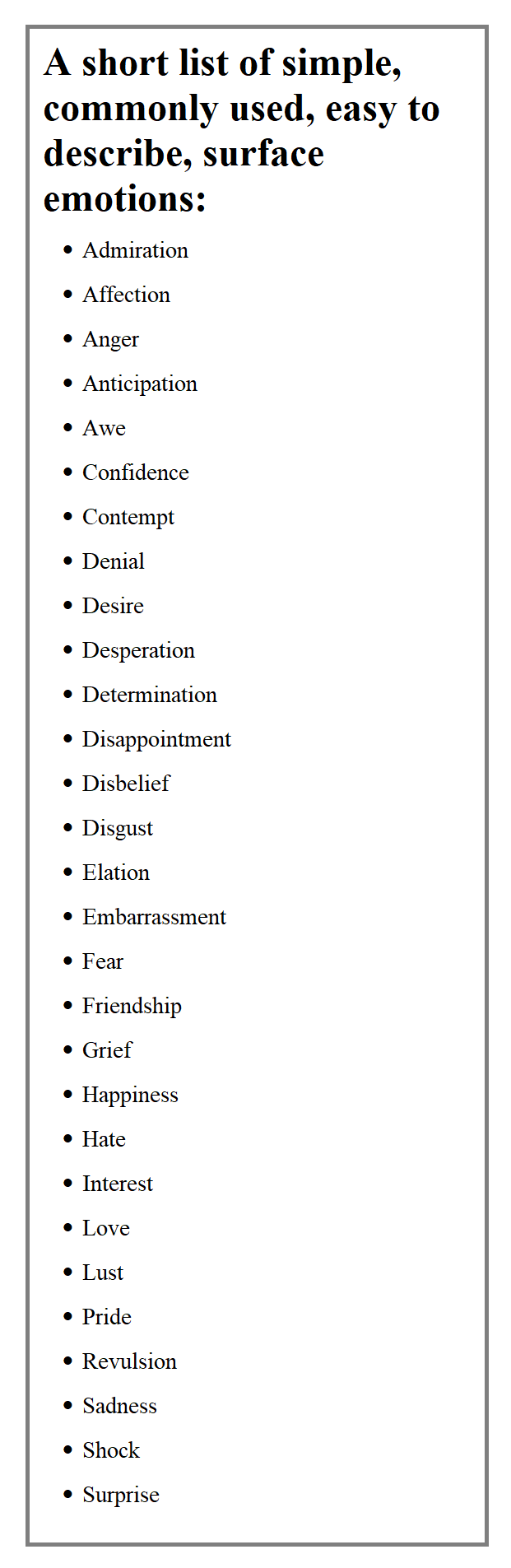

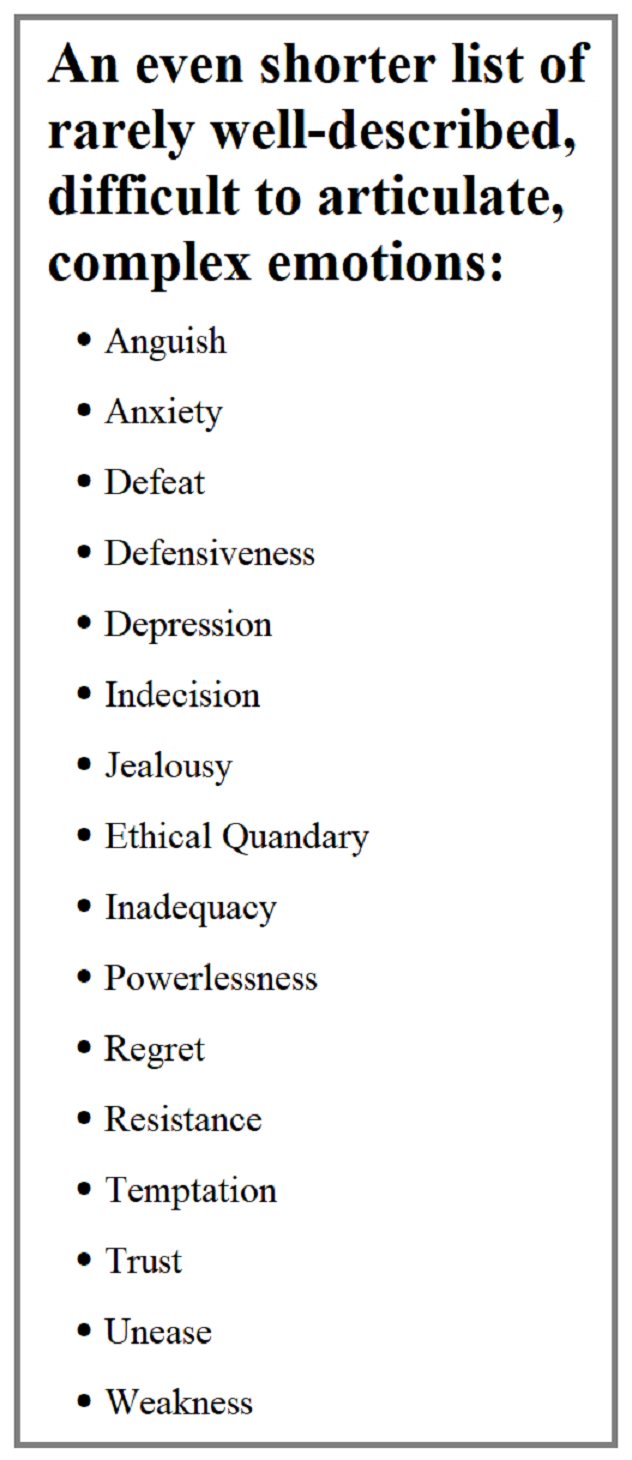

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood affects (and is affected by) the emotions evoked within the story. Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters.

Undermotivated emotions lack credibility and leave the reader feeling as if the story is flat. In real life, we have deep, personal reasons for our feelings, and so must our characters. Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere

Robert McKee tells us that the mood/dynamic of any story is there to make the emotional experience of our characters specific. It makes their emotions feel natural. After all, the mood and atmosphere