I have been accused of using too many words to say what I mean—and my critics were right. For the last four years, I have been on a quest to learn how to convey a story and keep my reader involved. I’ve had some successes and also failures. The successes keep me going, and every failure inspires me to figure out what went wrong.

I have been accused of using too many words to say what I mean—and my critics were right. For the last four years, I have been on a quest to learn how to convey a story and keep my reader involved. I’ve had some successes and also failures. The successes keep me going, and every failure inspires me to figure out what went wrong.

Most of the time it was my love of playing with words that derailed my story. Today’s example is a passage from an early work of mine. I will be rewriting this book over the course of the next few years, once the three books I am currently working on are published.

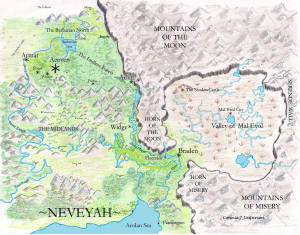

When I rewrite this book, I will eliminate the verbosity. I won’t change the basic story, only pare down the wordiness. This book was written for my first NaNoWriMo and was completely unplanned. I had no idea of what I was going to write until 12:01 a.m. on Nov. 1st, when I began writing it. In the back of my mind lurked Fritz Lieber’s great character, Fafhrd, although he’s not represented in this tale. Yet, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser influenced this tale.

It still shocks me that over the course of 21 days, a 92,000 word story about a group of mercenaries in a medieval Alternate Earth emerged from my subconscious mind.

The original manuscript is a great example of everything that is both wrong and right about a stream-of-consciousness first draft.

- Positive: It has a great, original plot,

- Positive: It has wonderful characters,

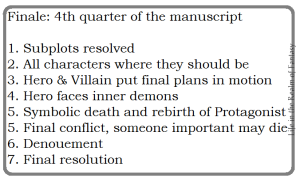

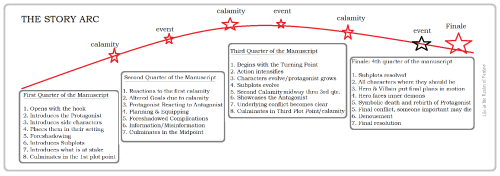

- Positive: It (surprisingly to me) has a basically good story arc.

- Positive: It ends well.

- Negative: I led off with an info dump.

- Negative: I used no contractions (Doh!)

- Negative: I made way too free with my adverbs and modifiers. This fluffed up the word-count by about 15,000 unnecessary words.

- Doubly negative: I used hokey phrasing, because I was trying to write well.

- Negative: Oh, and another info dump was inserted toward the end.

The example:

“I’ve brought along something so that we shall not have to boil the water to drink it,” ventured Lackland as he uncorked a bottle of wine. “Chicken Mickey was right about the trots you know, but I will never tell him that; the old thing enjoys mothering us so. It would take away the joy of nagging us to death if he thought we were able to care for ourselves.”

What? We shall not? From what hell hath this beast arisen? Still, once the hokey crap is pared away, something worth reading can be found.

SO, let’s take that unwieldy, 70-word behemoth of a paragraph apart and trim it down.

“I brought something so we won’t have to boil water to drink.” Lackland uncorked a bottle of wine. “Mick was right about the trots you know, but I’ll never tell him. It would take away the joy of nagging us to death.”

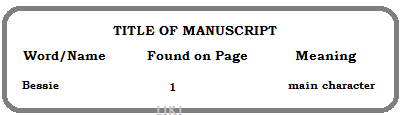

I trimmed it from 70 words to 42, and made it stronger without changing the meaning or intention. I changed the way Lackland refers to an absent friend, Chicken Mickey, the Rowdies’ supply-master. By this point in the ms, there is no need to use his full mercenary nickname every time he’s mentioned. Everyone knows Mick’s nickname and why he has it (he retired from the Rowdies to be a chicken farmer for a while, but that didn’t work out) so going with the short version of his given name, “Mick,” immediately helps that paragraph.

I trimmed it from 70 words to 42, and made it stronger without changing the meaning or intention. I changed the way Lackland refers to an absent friend, Chicken Mickey, the Rowdies’ supply-master. By this point in the ms, there is no need to use his full mercenary nickname every time he’s mentioned. Everyone knows Mick’s nickname and why he has it (he retired from the Rowdies to be a chicken farmer for a while, but that didn’t work out) so going with the short version of his given name, “Mick,” immediately helps that paragraph.

In the process, I axed one of my favorite sentences: “The old thing enjoys mothering us so.” It’s redundant as the sentiment is expressed in the sentence that follows, which also shows Mick’s character despite his absence.

Also of great benefit is the cutting away of unneeded words: along, to drink, ventured, as—these are words that can “go without saying” in the context of that paragraph. The reader understands they are there as silent partners: unwritten but understood. At this point, I feel that no dialogue tag is needed because Lackland has an action to perform, showing both who speaks and setting the scene.

Using contractions makes dialogue more natural. Some people would go even further than I did, and make “It would” a contraction. I don’t like the way “It’d” looks or sounds so I won’t do that—and that is part of what I think of as my voice. It is a deliberate usage choice, one that I prefer.

When I wrote the first draft of this manuscript, I was at a different stage in my writing development than I am at now. I had never been involved with a writing group, and I had never studied the mechanics of writing. The rudimentary skills I had were developed from trying to copy the styles of my favorite authors, but I had a limited understanding of the mechanics of writing fantasy fiction. The only writing I had done was for myself and my children, although I had done a lot of that.

While I had a standard high-school education and some college and had done a bit of writing in the course of my work, I realized I was woefully uneducated about the craft of writing. I made it my business to get an education, via the internet. It’s free and available to anyone who wants to learn. You just have to want to learn.

I began attending seminars, and writer’s conventions. I scavenged garage sales for books on the craft of writing and I joined local writing groups. I found other writers and made life-long friends, learning a great deal from them.

Nowadays, I have my own voice and my own style. I write far leaner prose in my first draft than I did in those days, and the editing process is not nearly such an ordeal as it was the first time I had one of my manuscripts edited professionally. I continue trying to learn the craft, updating my education constantly.

Choose your words carefully, so they express what you want to say clearly, and in as few words as is possible, while still conveying the atmosphere and mood.

Choose your words carefully, so they express what you want to say clearly, and in as few words as is possible, while still conveying the atmosphere and mood.

- Nothing can be included that does not advance the plot.

- There can be no idle conversations “just to show they’re human”: conversations must advance the story.

- We don’t need a chapter detailing the history behind the core conflict. Let that emerge as needed.

- Never use three words when one suffices.

- If you’re in love with a passage you wrote because it’s “great writing,” it probably should be cut.

- Ax all redundancies. It only has to be said once, unless the character has forgotten it, and that “forgetting” is a core part of the plot.

- Adverbs are important. They need to to be chosen carefully and used sparingly.

- If you occasionally love to wax poetic, go ahead and write poetry—just not in the middle of your political thriller. You have permission to love action-oriented genre fiction written with lean, mean prose, and still appreciate (and write) poetry.

What I didn’t know when I first began this journey is this: deleting the excess verbiage will add up to large gains, reducing the overall length of the book, increasing readability and (hopefully) the reader’s enjoyment.

Misplaced modifiers (frequently adverbs) make our work unclear, or “ambiguous.” The best way to avoid that ambiguity is to move the modifier so that your meaning is clear, or completely reword the sentence.

Misplaced modifiers (frequently adverbs) make our work unclear, or “ambiguous.” The best way to avoid that ambiguity is to move the modifier so that your meaning is clear, or completely reword the sentence.