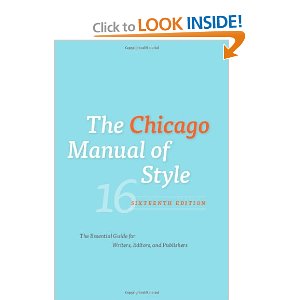

I use the internet for researching many things on a daily basis. However, in my office, some reference books must be in their hardcopy forms, such as The Chicago Manual of Style. I (and most other editors) rely on the CMOS, as it’s the most comprehensive style guide, and is geared for writers of essays and novels, fiction, and nonfiction.

I use the internet for researching many things on a daily basis. However, in my office, some reference books must be in their hardcopy forms, such as The Chicago Manual of Style. I (and most other editors) rely on the CMOS, as it’s the most comprehensive style guide, and is geared for writers of essays and novels, fiction, and nonfiction.

Strunk and White’s Elements of Style is an acceptable beginner style guide, but is presented in an arbitrary, arrogant fashion and sometimes runs contrary to commonly accepted practice. Strunk and White’s Elements of Style is still the same book it was when it was originally conceived, as it has not changed or evolved, despite the way our modern language has changed and evolved. Because the Elements of Style is somewhat antiquated in the rules it forces upon the writer, I no longer even own a copy of it.

Instead, I refer to my copy of The Chicago Manual of Style. If you are an author writing fiction you someday hope to publish, and have questions about sentence construction and word usage, this is the book for you. The researchers at CMOS realize that English is a living changing language, and when generally accepted practices within the publishing industry evolve, they evolve too.

Writing is not a one-size-fits-all kind of occupation. No one style guide will fit every purpose. Each kind of essay and type of book may be meant for a different reader, and each should be written with the style that meets the expectations of the intended readers.

The Chicago Manual of Style is written specifically for writers, editors and publishers of literary and genre fiction and is the publishing industry standard. The editors at the major publishing houses own copies and refer to this book when they have questions.

What is the best style guide for writing technical user manuals?

- Chicago Manual of Style (The Chicago Manual of Style Online)

- Microsoft Style for Technical Publication (Microsoft® Manual of Style, Fourth Edition)

Are you writing for a newspaper? AP style was developed for expediency in the newspaper industry and is not suitable for novels or for business correspondence, no matter how strenuously journalism majors try to push it forward. If you are using AP style, you are writing for the newspaper, not for literature. These are two widely different mediums with radically different requirements.

For business correspondence, you want to use the Gregg Reference Manual.

If you develop a passion for the words and ways in which we bend them, as I have done, you could soon find your bookshelf bowing under the weight of your reference books.

We’re driven to look at what we just wrote the day after we committed it to paper, despite our intent to let it rest. Did it say what I meant? How many times did I use the word “sword” in that paragraph and where am I going to find six different alternatives for such a unique weapon? Sword? Blade? Steel? After all, an epee is not a claymore, nor is it a saber.

Many readers have a little knowledge about weapons and will know more than other readers. If I mislabel a blade, they could note my lack of knowledge with an uncomplimentary review, so I have done my research and continue to study medieval weaponry. My characters swing a claymore-style of sword which is rarely referred to as ‘steel,’ so I never refer to it that way. In literature, ‘steel’ is more commonly used for epees and rapiers, which are radically different weapons from the claymore.

Sometimes we get stuck on a word and can’t think of any alternatives. For that reason, I have the Oxford American Writers’ Thesaurus on my desk, and I refer to it regularly. This book is far more comprehensive than Roget’s’ Thesaurus, even more so than the online version. I have found it saves time to use the hardcopy book rather than the internet because I am not so easily distracted and led down rabbit trails.

Sometimes we get stuck on a word and can’t think of any alternatives. For that reason, I have the Oxford American Writers’ Thesaurus on my desk, and I refer to it regularly. This book is far more comprehensive than Roget’s’ Thesaurus, even more so than the online version. I have found it saves time to use the hardcopy book rather than the internet because I am not so easily distracted and led down rabbit trails.

If you only have two books on your desk, one should be the Chicago Manual of Style, and the other should be the Oxford American Writers’ Thesaurus. Besides those two books, these are a few of the books I keep in hardcopy and refer to regularly:

Story, by Robert McKee

Dialogue, by Robert McKee

The Writer’s Journey, by Christopher Vogler

The Sound on the Page, by Ben Yagoda

Rhetorical Grammar, by Martha Kolin and Loretta Gray

You may not be able to afford to take writing classes or have the time to go to college and get that degree. But you may be able to afford to buy a few books on the craft, and it’s to your advantage to try to build your reference library with books that speak to you and your style. You will gravitate to books that may be different than mine, and that is good. But some aspects of our craft are absolute, nearly engraved in stone, and these are the basic concepts you will find explained in these manuals.

Education comes in many forms, and it’s up to you to take advantage of every opportunity to learn and grow as an author.