The story arc can take several forms. It can be linear, a straight shot from the inciting incident to the conclusion. This kind of story takes our protagonist through a series of events that all lead to one ending, a point well away from where it began. The protagonist has left his roots behind and is transformed into a hero.

Another arc takes the protagonist on a journey that can end several different ways, all of them taking our characters down a winding path with many choices, roads not taken. They also are altered by their experiences for good or ill.

Another arc takes the protagonist on a journey that can end several different ways, all of them taking our characters down a winding path with many choices, roads not taken. They also are altered by their experiences for good or ill.

Yet another arc takes the protagonist back to their beginnings, transformed and ready to face their future.

My favorite arc to play with is the double circular arc, also known as the infinity arc. The majority of this post appeared here in November 2023, so if you have read it already, thank you for stopping by. The infinity arc is on my mind as it’s a method I am employing in a current short work-in-progress.

When I plan a story, I divide the outline into 3 acts. In a 2,000-word story, act 1 has 500 words, act 2 has 1,000, and act 3 has 500 more words to wind up the events. No matter the length of any story, if you know the intended word count, you can divide the plot outline that way.

Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc.

Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc.

In any story, the words we use to show the setting, combined with a strong theme, will convey atmosphere and mood, so fewer words are needed.

The story I’m using for today’s example is the Iron Dragon, a 1,025-word story I wrote during NaNoWriMo 2015. That was the year I focused on experimental writing, putting out at least one short story every day and sometimes two.

This is a story of the web of time glitching and the perceptions of the characters who experienced it.

Some speculative fiction stories work well as a double circular arc—something like an infinity sign, a figure-eight lying on its side: ∞

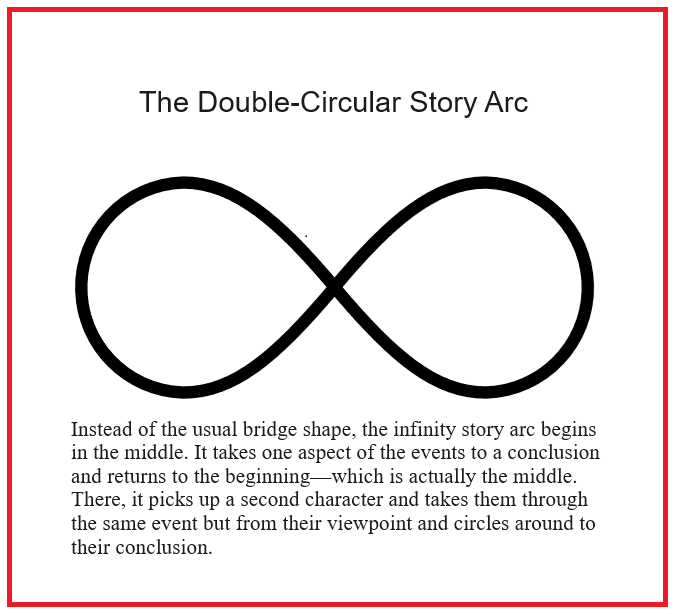

In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

The infinity arc presents one story from two different viewpoints. The story begins with character 1, takes them through the events, and brings them back. At that point, the story takes up character 2 and retells the events through their point of view, bringing them back to where they began. (Two circular story arcs joined by one event.)

Both characters begin at the same place, experience the event(s) concurrently but separately, and arrive back at the same place. The worldview of both is challenged by what they have lived through.

The two characters may not meet. In the Iron Dragon, my characters physically don’t meet in person. However, they briefly occupy the same patch of ground during a glitch in the space-time continuum.

This story ends where it began but with the two sets of characters having seemingly experienced two different events. Their perception of the meeting is colored by the knowledge and superstitions of their respective eras.

The first paragraph of the Iron Dragon begins in the middle of a story—the center of the infinity sign. Those opening sentences establish the world, set the scene, and introduce the first protagonist. The following three paragraphs show the situation and establish the mood. They also introduce the antagonist—what appears to be an immense dragon made of iron.

At this point, our first protagonist knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people, which he does. There is more to his side of the story, of course. But this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story.

Again, I had to set the scene and establish the mood and characters. Here, we meet the second protagonist, an engine driver named Owen. He has the same needs as Aeddan and also resolves the problem. Neither character would have understood the strange physics of what just occurred had Michio Kaku been around to explain it to them. Both do what they must to protect their people.

The final paragraphs wind it up. They also contribute to the overall atmosphere and setting of the second part of the story. As a practice piece, this story has good bones. I didn’t feel it was the right kind of story for submission to a magazine or contest, as it’s not a commercially viable piece. So, I posted it here on this blog on November 4th, 2016. #flashfictionfriday: The Iron Dragon

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch).

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch).

But I also wanted to use the double circular story arc, seeing it as a way to tell one story as lived by two protagonists separated by twelve centuries and a multitude of legends. That meant I had 1000 words to tell two stories.

Short fiction allows us to experiment with both style and genre. It challenges us to build a world in only a few words and still tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The act of writing something different, a little outside my comfort zone, forces me to be more imaginative in how I tell my stories. It makes me a better reader as well as a better writer.

Credits and Attributions:

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Flag of Wales.svg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flag_of_Wales.svg&oldid=808619174 (accessed November 19, 2023).

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be.

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be. Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it.

So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it. Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice.

Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice. Tad Williams

Tad Williams Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning. I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending. Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals. Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

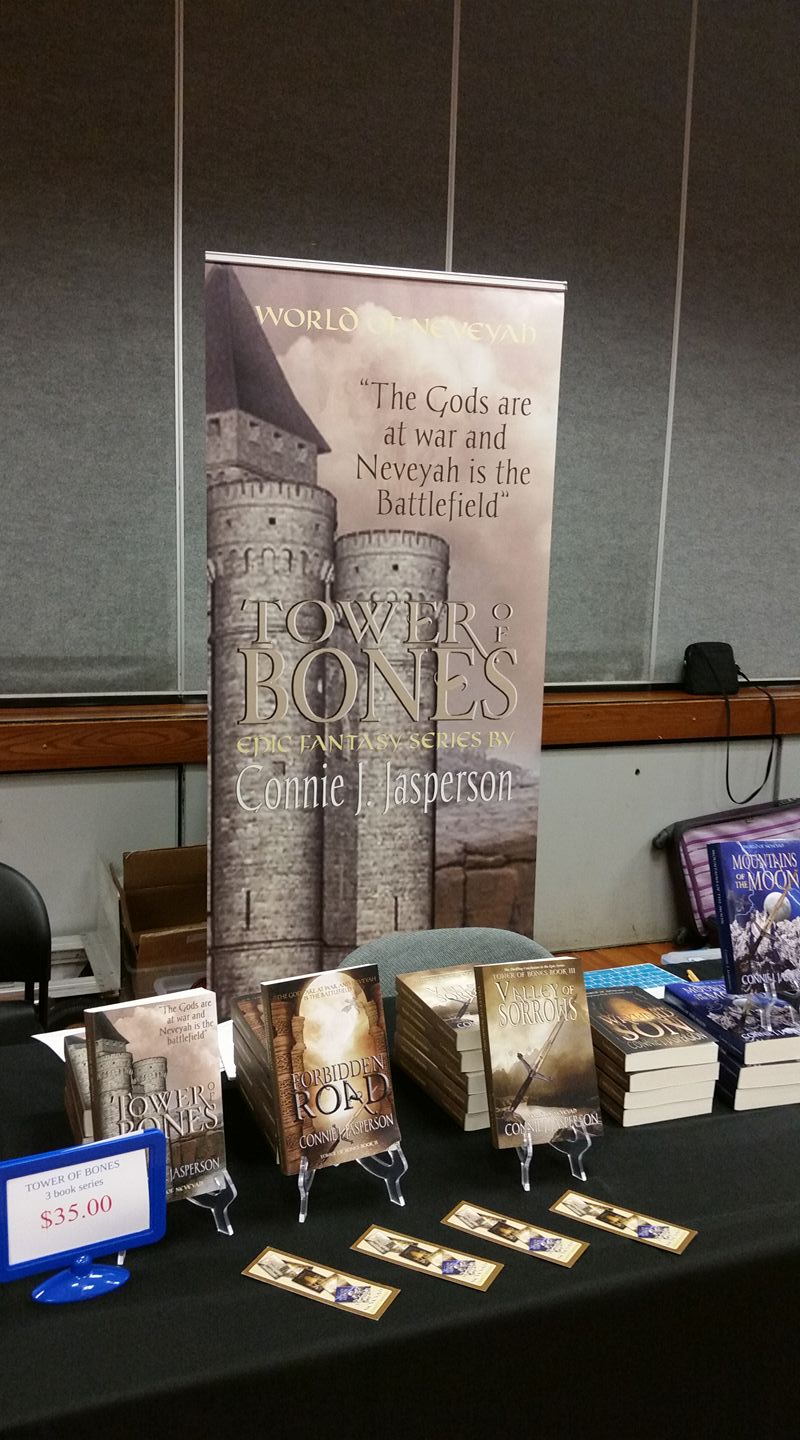

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you.

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you. The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins.

Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins. Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.

I think of poetry and language as coming into existence as conjoined twins. I can remember anything I can set to a rhyme or make into a song.

I’m not educated as an art historian and would never claim to be one. I’m just a woman who loves the paintings of great artists because they tell a story. Thanks to Wikimedia Commons, an online museum of sorts, anyone with access to the internet can see the great art and photography of the past and the present.

I’m not educated as an art historian and would never claim to be one. I’m just a woman who loves the paintings of great artists because they tell a story. Thanks to Wikimedia Commons, an online museum of sorts, anyone with access to the internet can see the great art and photography of the past and the present.

I love the chaos in this painting. Is this a New Year’s party? Whatever they are celebrating, they’re having a great time.

I love the chaos in this painting. Is this a New Year’s party? Whatever they are celebrating, they’re having a great time. Perhaps so. But take the time to write those thoughts down. Your notes could become a storyboard, which could become a novel.

Perhaps so. But take the time to write those thoughts down. Your notes could become a storyboard, which could become a novel. Artist: John Constable (1776–1837)

Artist: John Constable (1776–1837) The posts I wrote for that first attempt at blogging were pathetic attempts to write about current affairs and politics as a journalist, which is something that has never interested me. I was lucky if I managed to post one piece a month and had no readers or followers.

The posts I wrote for that first attempt at blogging were pathetic attempts to write about current affairs and politics as a journalist, which is something that has never interested me. I was lucky if I managed to post one piece a month and had no readers or followers. Books.

Books. I’ve made many friends through this writing adventure. I now know people from all over the world who I may never meet in person but who I am fond of, nevertheless.

I’ve made many friends through this writing adventure. I now know people from all over the world who I may never meet in person but who I am fond of, nevertheless. Life in the Realm of Fantasy has evolved over the years because I have changed and matured as an author.

Life in the Realm of Fantasy has evolved over the years because I have changed and matured as an author. Artist: Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904)

Artist: Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904)