When I have an idea for a new writing project, I ask myself, “What genre will be best for this story?” This is important because how I incorporate certain expected tropes will determine what kind of reader will be interested in this novel.

I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction.

I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction.

I think of a novel as if it were a painting created from words. The story is the picture, and the genre is the frame. When selecting the frame for a picture, what are my choices? Perhaps a heavily carved and gilded frame (literary fiction), or maybe simple polished wood (fiction that appeals to a broader range) … or should we go with sleek polished steel (sci-fi)? I’ll usually opt for the simple wooden frame.

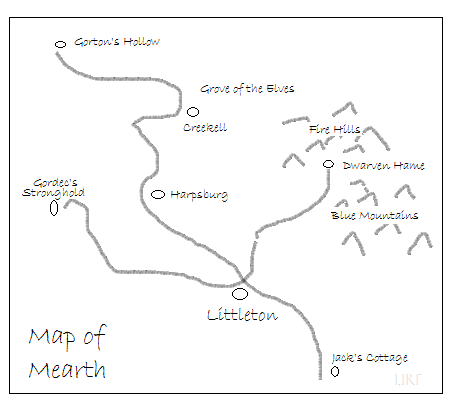

The many subgenres of fantasy usually incorporate aspects of magic, mythical beasts, vampires, or other races, such as elves or dwarves, into the story. These tropes are often used as the set-dressing part of worldbuilding, even when they are characters in that story.

But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters.

But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters.

- Who are the players?

- Who is the POV character?

- At what point in their drama does the story open?

- What does the protagonist have to say about their story?

- How did they arrive at the point of no return?

- What do they want, and what will they do to get it?

- What stands in their way, and how will they get around it?

- How does their story end? Is there more than one way this could go?

So, now we discover who the players are. My stories always begin with the characters, but the ideas for them come to me out of nowhere.

Characters usually arrive in my imagination as new acquaintances inhabiting a specific environment. That world determines the genre.

The idea-seed that became the three Billy’s Revenge novels came about in 2010 when I was challenged to participate in something called NaNoWriMo. It wasn’t really a challenge—it was more of a dare, and I can’t pass one of those up.

Anyway, I had been working on several writing projects for the previous two years and didn’t want to begin something new. But one autumn evening, a random thought occurred to me. What happens when a Hero gets too old to do the job? How does a Hero gracefully retire from the business of saving the world?

Then I thought, perhaps he doesn’t.

Maybe there are so few Heroes that there is no graceful retirement. And then I wondered, how did he find himself in that position in the first place? He had been young and strong once. He must have had companions. Why did he not quit when he was ahead? At that point, I had my story.

And thus Julian Lackland and Lady Mags were born, and Huw the Bard and Golden Beau. But they needed a place to live, so along came Billy Ninefingers, captain of the Rowdies, and his inn, Billy’s Revenge. When I first met Billy and his colorful crew of mercenaries, I was hooked. I had to write the tale that became three novels: Julian Lackland, Billy Ninefingers, and Huw the Bard.

And thus Julian Lackland and Lady Mags were born, and Huw the Bard and Golden Beau. But they needed a place to live, so along came Billy Ninefingers, captain of the Rowdies, and his inn, Billy’s Revenge. When I first met Billy and his colorful crew of mercenaries, I was hooked. I had to write the tale that became three novels: Julian Lackland, Billy Ninefingers, and Huw the Bard.

The fantasy subgenre for that series is “alternate medieval world” because the characters live in a low-tech society with elements of feudalism. Waldeyn is an alternate world because I imagined it as a mashup of 16th-century Wales, Venice, and Amsterdam with a touch of modern plumbing. I gave women the right to become mercenary knights as a way of escaping the bonds of society.

It’s never mentioned in the books, but I have always seen Waldeyn as a human-colonized world. Magic occurs in that world as a component of nature, and it affects the flora and fauna. It spawns creatures like dragons, but the dangerous environment and creatures aren’t the point of those books. I see it as a colony cut off from its home world, one that nearly lost the battle to survive but found a way to make it work. Now, a millennium later, they no longer remember their origin and don’t care.

Once I have an idea for a protagonist, I imagine them as people who begin sharing some of their stories the way strangers on a long bus ride might.

I sit and write one or two paragraphs about them as if meeting them for a job interview. They tell me some things about themselves. At first, I only see the image they want the world to see. As strangers always do, they keep most of their secrets close and don’t reveal all the dirt.

However, that little word picture of the face they show the world is all I need to get my story off the ground when the real writing begins.

Excalibur London_Film_Museum_ via Wikipedia

The unspoken bits of human error and hidden truths they wish to conceal are still mysteries. But those secrets will be pried from them over the course of writing the narrative’s first draft.

Knowing who your characters might be, having an idea of their story, and seeing them in their world is a good first step. Write those thoughts down so you don’t lose them. Keep writing as the ideas come to you, and soon, you’ll have the seeds of a novel.

And I will be here to read it.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

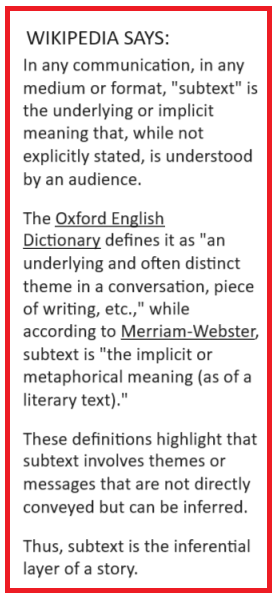

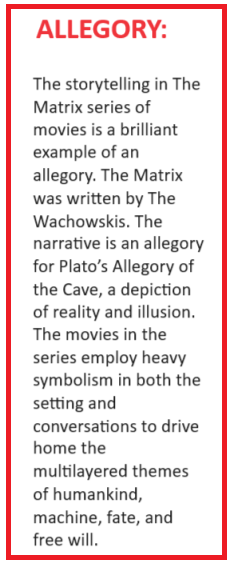

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions. Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere. We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood. When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

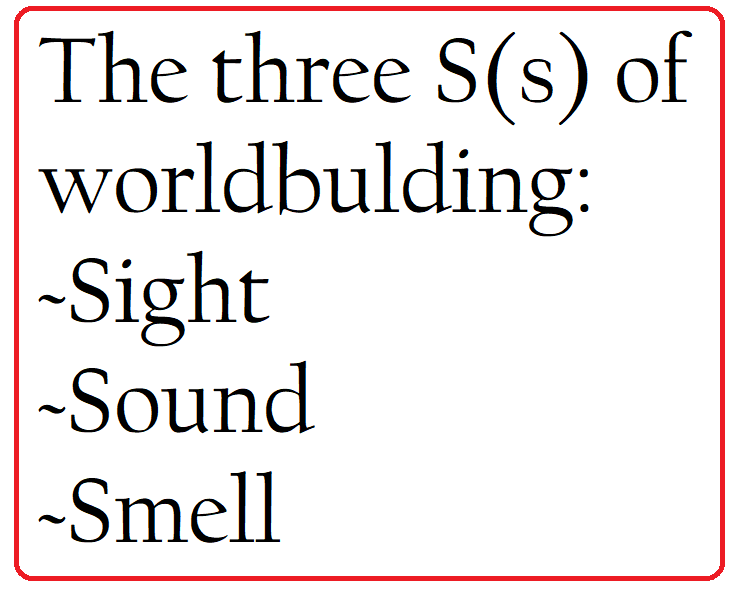

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood. We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene. Artist: Elin Danielson-Gambogi (1861–1919)

Artist: Elin Danielson-Gambogi (1861–1919) Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies.

Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies. We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government.

We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government. Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions.

Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions. Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress.

Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress. First, is this character someone the reader should remember? Even if they offer information the protagonist and reader must know, it doesn’t necessarily mean they must be named. Walk-through characters provide clues to help our protagonist complete their quest, but we never see them again. They can show us something about the protagonist and give hints about their personality or past—but when they are gone, they are forgotten.

First, is this character someone the reader should remember? Even if they offer information the protagonist and reader must know, it doesn’t necessarily mean they must be named. Walk-through characters provide clues to help our protagonist complete their quest, but we never see them again. They can show us something about the protagonist and give hints about their personality or past—but when they are gone, they are forgotten. Novelists can learn a lot from screenwriters about writing good, concise scenes. An excellent book on crafting scenes is

Novelists can learn a lot from screenwriters about writing good, concise scenes. An excellent book on crafting scenes is  I took this absurdity to an extreme in

I took this absurdity to an extreme in  One final thing to consider is this: how will that name be pronounced when read aloud? You may not think this matters, but it does. Audiobooks are becoming more popular than ever. You want to write it so a narrator can easily read that name aloud.

One final thing to consider is this: how will that name be pronounced when read aloud? You may not think this matters, but it does. Audiobooks are becoming more popular than ever. You want to write it so a narrator can easily read that name aloud. Despite my experience of reading fantasy books aloud to my children, it didn’t occur to me that the names were unpronounceable as they were written. We ironed that out, but that hiccup taught me to spell names the way they’re pronounced whenever possible.

Despite my experience of reading fantasy books aloud to my children, it didn’t occur to me that the names were unpronounceable as they were written. We ironed that out, but that hiccup taught me to spell names the way they’re pronounced whenever possible. Use common sense and if a beta reader runs amok in your manuscript telling you to remove “this and that,” examine each instance of what has their undies in a twist and try to see why they are pointing it out.

Use common sense and if a beta reader runs amok in your manuscript telling you to remove “this and that,” examine each instance of what has their undies in a twist and try to see why they are pointing it out. Many writers have beta readers look at their work before it is submitted. I would also suggest hiring a freelance editor. Besides having a person pointing out where you need to insert or delete a comma, hiring a freelance editor is a good way to discover many other things you don’t want to include in your manuscript, things you are unaware are in there:

Many writers have beta readers look at their work before it is submitted. I would also suggest hiring a freelance editor. Besides having a person pointing out where you need to insert or delete a comma, hiring a freelance editor is a good way to discover many other things you don’t want to include in your manuscript, things you are unaware are in there: Freelance editors will point out these all things. We don’t like it when certain flaws in our work are pointed out, but we are better off knowing what needs addressing. When an editor guides you away from detrimental writing habits, they aren’t trying to change your voice. They’ve seen something good in your work, and they’re pointing out places where you can tighten it up and grow as a writer.

Freelance editors will point out these all things. We don’t like it when certain flaws in our work are pointed out, but we are better off knowing what needs addressing. When an editor guides you away from detrimental writing habits, they aren’t trying to change your voice. They’ve seen something good in your work, and they’re pointing out places where you can tighten it up and grow as a writer. In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.

In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English. Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

I have a lot of words to choose from, and

I have a lot of words to choose from, and  Writing groups can be quite different in their areas of focus. Some are critique groups, and some are more support groups. No matter what the group focuses on in its meetings, the anthology is meant to showcase that group’s professionalism.

Writing groups can be quite different in their areas of focus. Some are critique groups, and some are more support groups. No matter what the group focuses on in its meetings, the anthology is meant to showcase that group’s professionalism. “Your best work” gets off to a great start when the story is written with the central theme of the anthology in mind, a central facet of the story.

“Your best work” gets off to a great start when the story is written with the central theme of the anthology in mind, a central facet of the story. The editors have said that one can face the reality of the past, present, or future—it’s up to each author to write their story. We must find ways to layer that theme into the character arcs, plot, and world building.

The editors have said that one can face the reality of the past, present, or future—it’s up to each author to write their story. We must find ways to layer that theme into the character arcs, plot, and world building. Basically, his guidelines say you must use Times New Roman (or sometimes Courier) .12 font. You must also ensure your manuscript is formatted as follows:

Basically, his guidelines say you must use Times New Roman (or sometimes Courier) .12 font. You must also ensure your manuscript is formatted as follows: The editor of the anthology has posted a public call for the best work that authors can provide, and they will receive a landslide of submissions. They will receive far more stories than they will have room for, and the majority of them will be memorable, wonderful stories.

The editor of the anthology has posted a public call for the best work that authors can provide, and they will receive a landslide of submissions. They will receive far more stories than they will have room for, and the majority of them will be memorable, wonderful stories. When your spouse has Parkinson’s, problems tend to arrive en masse, like an unstoppable horde of lemmings. Dealing with life’s lemmings requires a bit more creativity than merely making a cool, relaxing drink. While you may never gain control of the migrating mob, you must somehow steer them in the right direction.

When your spouse has Parkinson’s, problems tend to arrive en masse, like an unstoppable horde of lemmings. Dealing with life’s lemmings requires a bit more creativity than merely making a cool, relaxing drink. While you may never gain control of the migrating mob, you must somehow steer them in the right direction. Wikipedia says:

Wikipedia says: But back to the lemmings. We know how mob mentality works in humans, and it seems to happen in other creatures.

But back to the lemmings. We know how mob mentality works in humans, and it seems to happen in other creatures. Two weeks ago, my husband fell, sustaining a minor injury. Two days later, he was fighting off an infection, and we spent last Saturday in Urgent Care from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm. Rather than put him in the hospital, we were given the chance to participate in the

Two weeks ago, my husband fell, sustaining a minor injury. Two days later, he was fighting off an infection, and we spent last Saturday in Urgent Care from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm. Rather than put him in the hospital, we were given the chance to participate in the  No one is perfect, but I like to do my best work. I’ll admit that publishing a post discussing a picture but with no image of that art piece is a humorous blooper. We did get a laugh out of it.

No one is perfect, but I like to do my best work. I’ll admit that publishing a post discussing a picture but with no image of that art piece is a humorous blooper. We did get a laugh out of it. I try to write my posts on Saturdays and proof them on Sundays, so having only two to deal with will allow me time to proofread them and work on my other creative writing projects.

I try to write my posts on Saturdays and proof them on Sundays, so having only two to deal with will allow me time to proofread them and work on my other creative writing projects.