When I sit down to write a scene, my mind sees it as if through a camera, as if my narrative were a movie. The character and their actions are framed by the setting and environment. In so many ways, a writer’s imagination is like a camera, and as they write that first draft, the narrative unfolds like a movie.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Directors will tell you they focus the scenery (set dressing) so it frames the action. The composition of props in that scene is finely focused world-building, and it draws the viewer’s attention to the subtext the director wants to convey.

Subtext is what lies below the surface. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning that shapes the narrative. It’s conveyed by the composition of the images we place in the environment and how they affect our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

As I work my way through revisions, I struggle to find the right set dressing to underscore the drama. Each item mentioned in the scene must emphasize the characters’ moods and the overall atmosphere of that part of the story.

Subtext supports the dialogue and gives purpose to the personal events. What furnishings, sounds, and odors are the visual necessities to support that scene? How can I best frame the interactions so that the most information is conveyed with the fewest words? And how do we chain our scenes together to create a smooth flow to our narrative?

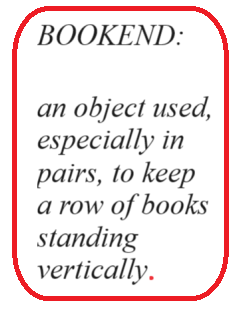

We all struggle with transitions, and one helpful tool is this: we can bookend our scenes. But how does bookending work?

Last week, we talked about transitions and how they affect pacing, but we didn’t have time to expand on the mechanics. We want the events to unfold naturally so the plot flows logically.

Perhaps we have the plot all laid out in the right order. We know what must happen in this event so that the next event makes sense. But how do we move from this event to the next in such a way that the reader doesn’t notice the transitions?

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

We can bookend the event with “doorway” scenes. These scenes determine the narrative’s pacing, which is created by the rise and fall of action.

Pacing consists of doing and showing linked together with a little telling. An example of an opening paragraph (from a short story) that conveys visual information is this:

Olin Erikson gazed at the remains of his barn. He turned back to Aeril, his nine-year-old son. “I know you didn’t shake our barn down intentionally, but it happened. I sense that you have a strong earth-gift, and you’ve been trying to hide it.”

In that particular short story, the opening paragraph consists of 44 words. It introduces the characters and tells you they have the ability to use magic. It also introduces the inciting incident. But bookends come in pairs, so what does a final paragraph do?

Another example is one I have used before. This next scene is the last paragraph of an opening chapter. Page one of the narrative opens with a short paragraph introducing the character—the hook. This is followed by a confrontation scene that introduces the inciting incident. Finally, we need to keep the reader hooked. The paragraph that follows here is the final paragraph of that introductory chapter:

I picked up my kit and looked around. No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance. I’d hit bottom, so things could only get better. Right?

While that particular narrative is told from the first-person point of view, any POV would work.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The opening paragraph of a chapter and the ending paragraph are miniature scenes that bookend the central action scene. They are doors that lead us into the event and guide us on to the next hurdle the character must overcome.

The objects my protagonists observe in each mini-scene allow the reader to infer a great deal of information about them and their actions. This is world-building and is crucial to how the reader visualizes the events.

Transition scenes are your opportunity to convey a lot of information with only a few words.

The character in the above transition scene performs an action and moves on to the next event. It reveals his mood and some of his history in 56 words of free indirect speech and propels him into the next chapter.

He does something: I picked up my kit and looked around. He performs an action in only 8 words, and that action gives us a great deal of information. It tells us that he is preparing to leave on an extended journey.

He shows us something: No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. In 26 words, he shows us a barren existence and offers us his self-evaluation as a failure.

He tells us something: The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance. I’d hit bottom, so things could only get better. Right? 22 words show us his state of mind. The door has closed on an episode in his life, and he has no intention of going back.

This paragraph ends the chapter.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

When the next chapter opens, he steps into an opening paragraph that leads into the next action sequence. We find out who and what new misery is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

Small bookend scenes should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They don’t take up a lot of space, and they lay the groundwork for what comes next, subtly moving us forward.

One way to ensure the events of your story occur in a plausible way is to open a new document and list the sequence of events in the order in which they have to happen. That way, you can view the story as a whole and move events forward or back along the timeline to ensure a logical sequence.

The brief transition scene does the heavy lifting when it comes to conveying information. It is the best opportunity for clues about the characters and their history to emerge without an info dump.

A “thinking scene” opens a window for the reader to see how the characters see themselves.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

When you begin making revisions, take a look at the opening paragraph of each chapter. Ask yourself how it could be rewritten to convey information and lead the reader into the action. Then, look at the final paragraph and ask yourself the same question.

Finding the right words to hook a reader, land them, and keep them hooked is a lot of work, but it will be worth it.

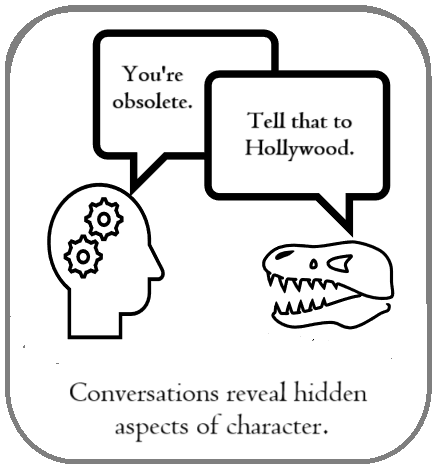

These transitions are often small moments of conversation, italicized thoughts (internal dialogues), or contemplations written as free indirect speech. These moments are a form of action that can work well when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. The reader and the characters receive information simultaneously, but only when they need it.

These transitions are often small moments of conversation, italicized thoughts (internal dialogues), or contemplations written as free indirect speech. These moments are a form of action that can work well when a hard break, such as a new chapter, doesn’t feel right. The reader and the characters receive information simultaneously, but only when they need it. A character’s personal mood can be shown in many ways. A moment of

A character’s personal mood can be shown in many ways. A moment of  Trim that back to

Trim that back to  The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a scene is to stay only in one person’s head. You can show different characters’ internal workings, provided you have a hard scene or chapter break between each character’s dialogue.

The main thing to watch for when employing indirect speech in a scene is to stay only in one person’s head. You can show different characters’ internal workings, provided you have a hard scene or chapter break between each character’s dialogue.

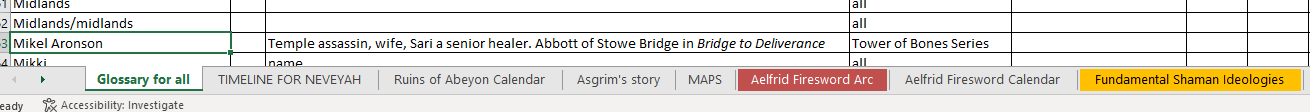

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun.

As stories unfold on paper, new characters enter. They bring their dramas and the story goes in a different direction than was planned. When I meet these imaginary people, I assign their personalities a verb and a noun. Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau.

Julian’s noun is chivalry (Gallantry, Bravery, Daring, Courtliness, Valor, Love). He sees himself as a good knight and puts all his effort into being that person. He is in love with both Mags and Beau. Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms:

Next, we assign a verb that describes their gut reactions, which will guide how they react to every situation. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Again, we also look at sub-verbs and synonyms: Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was:

Have you thought about the two words that describe the primary weaknesses of your characters, the thing that could be their ultimate ruin? In the case of Julian’s story, it was: Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books

Julian Lackland took ten years to get from the 2010 NaNoWriMo novel to the finished product. He spawned the books

I hate it when I find myself at the point where I am fighting the story, forcing it onto paper. It feels like admitting defeat to confess that my story has taken a wrong turn so early on, and I hate that feeling. Fortunately, I knew by the 40,000-word point that last year’s story arc had gone so far off the rails that there was no rescuing it.

I hate it when I find myself at the point where I am fighting the story, forcing it onto paper. It feels like admitting defeat to confess that my story has taken a wrong turn so early on, and I hate that feeling. Fortunately, I knew by the 40,000-word point that last year’s story arc had gone so far off the rails that there was no rescuing it. The sections I cut weren’t a waste, they were a detour. In so many ways, that sort of thing is why it takes me so long to write a book—each story contains the seeds of more stories.

The sections I cut weren’t a waste, they were a detour. In so many ways, that sort of thing is why it takes me so long to write a book—each story contains the seeds of more stories. Sometimes, something different happens. In 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist and is what I am currently working on. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so for the paperback version, I will break it into two novels. That will keep my costs down.

Sometimes, something different happens. In 2019, I realized the novel I was writing is actually two books worth of story. The first half is the protagonist’s personal quest and is finished. The second half resolves the unfinished thread of what happened to the antagonist and is what I am currently working on. Both halves of the story have finite endings, so for the paperback version, I will break it into two novels. That will keep my costs down. For those of you who are curious—I have the attention span of a sack full of squirrels. Proof of that can be found in the 4 novels currently in progress that are set in that world, each at different eras of the 3000-year timeline, each in various stages of completion.

For those of you who are curious—I have the attention span of a sack full of squirrels. Proof of that can be found in the 4 novels currently in progress that are set in that world, each at different eras of the 3000-year timeline, each in various stages of completion. think of

think of  In 1953’s

In 1953’s  Neil Gaiman’s

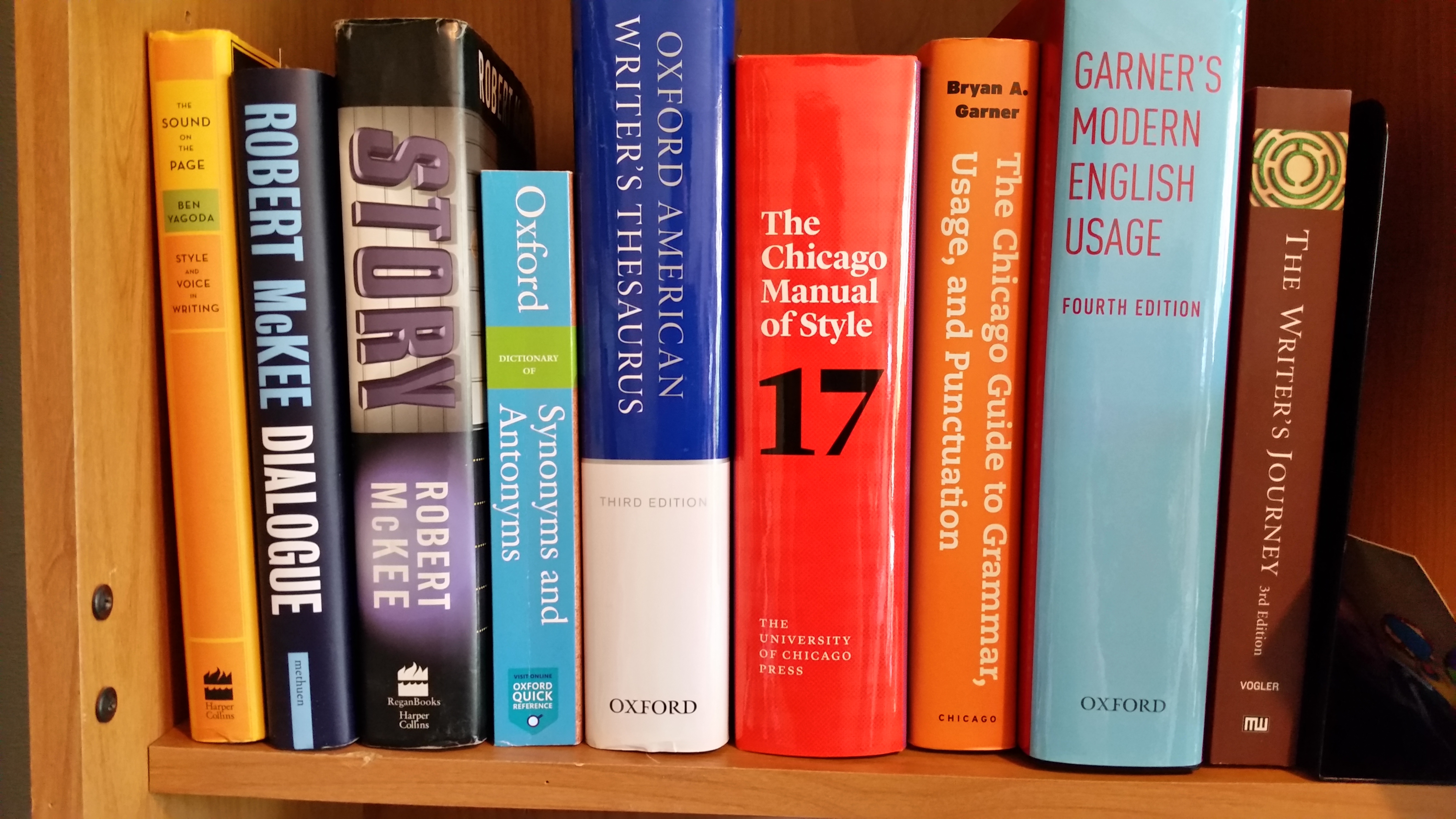

Neil Gaiman’s  Dedicated authors are driven to learn the craft of writing, and it is a quest that can take a lifetime. It is a journey that involves more than just reading “How to Write This or That Aspect of a Novel” manuals. Those are important and my library is full of them. But how-to manuals only offer up a part of the picture. The rest of the education is within each of us, an amalgamation of our life experiences and what we have learned along the way.

Dedicated authors are driven to learn the craft of writing, and it is a quest that can take a lifetime. It is a journey that involves more than just reading “How to Write This or That Aspect of a Novel” manuals. Those are important and my library is full of them. But how-to manuals only offer up a part of the picture. The rest of the education is within each of us, an amalgamation of our life experiences and what we have learned along the way. Authors write because we have a story to tell, one that might also embrace morality and the meaning of life. To that end, every word we put to the final product must count if our ideas are to be conveyed.

Authors write because we have a story to tell, one that might also embrace morality and the meaning of life. To that end, every word we put to the final product must count if our ideas are to be conveyed.

The second piece of wisdom is a little more challenging but is a continuation of the first point: Write something new every day, even if it is only one line. Your aptitude for writing grows in strength and skill when you exercise it daily. This is where blogging comes in for me—it’s my daily exercise. If you only have ten minutes free, use them to write whatever enters your head, stream-of-consciousness.

The second piece of wisdom is a little more challenging but is a continuation of the first point: Write something new every day, even if it is only one line. Your aptitude for writing grows in strength and skill when you exercise it daily. This is where blogging comes in for me—it’s my daily exercise. If you only have ten minutes free, use them to write whatever enters your head, stream-of-consciousness. The story is the goal; everything else is a bonus.

The story is the goal; everything else is a bonus. The well of inspiration runs dry and they quit. Many will never attempt to write again, although they will always consider themselves secretly a writer.

The well of inspiration runs dry and they quit. Many will never attempt to write again, although they will always consider themselves secretly a writer. The first one is one I developed when working in corporate America. Frequently, my best ideas came to me while I was at my job. If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. To work around that, keep a pocket-sized notebook and pen to write those ideas down as they come to you.

The first one is one I developed when working in corporate America. Frequently, my best ideas came to me while I was at my job. If your employment isn’t a work-from-home job, using the note-taking app on your cellphone to take notes during business hours will be frowned upon. To work around that, keep a pocket-sized notebook and pen to write those ideas down as they come to you.

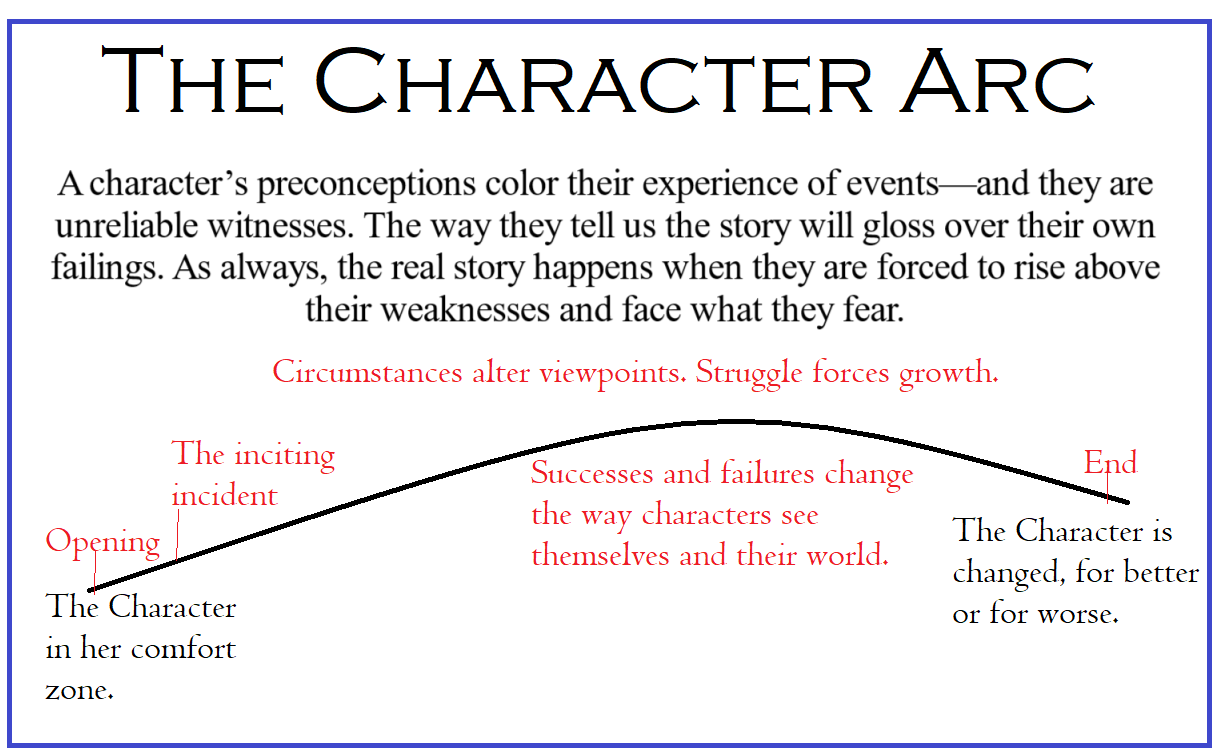

Every obstacle we throw in the path to happiness for the protagonists and their opposition shapes the narrative’s direction and alters the characters’ personal growth arcs. As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come.

Every obstacle we throw in the path to happiness for the protagonists and their opposition shapes the narrative’s direction and alters the characters’ personal growth arcs. As you clarify why the protagonist must struggle to achieve their goal, the words will come. Finally, let’s talk about murder as a way to kickstart your inspiration. Some people recommend it but I suggest you don’t resort to suddenly killing off characters just to get your mind working. You may need that character later, so plan your deaths accordingly.

Finally, let’s talk about murder as a way to kickstart your inspiration. Some people recommend it but I suggest you don’t resort to suddenly killing off characters just to get your mind working. You may need that character later, so plan your deaths accordingly.

The writer of true science fiction must know the difference, especially when creating possible weapons. Superweapons and superpowers are science-based. Think

The writer of true science fiction must know the difference, especially when creating possible weapons. Superweapons and superpowers are science-based. Think  Magic works best when the local population in that world accepts that it exists and has limitations. When you think about it, magic should only be possible if certain conditions have been met. It should follow a set of rules.

Magic works best when the local population in that world accepts that it exists and has limitations. When you think about it, magic should only be possible if certain conditions have been met. It should follow a set of rules. Conflict forces the characters out of their comfortable environment. The roadblocks you put up force the protagonist to be creative. Through that creativity, your characters become stronger than they believe they are.

Conflict forces the characters out of their comfortable environment. The roadblocks you put up force the protagonist to be creative. Through that creativity, your characters become stronger than they believe they are. However, neither science nor magic can support a poorly conceived novel. Science, the supernatural, and magic are just tropes, tools we use to help tell the story. Strong, charismatic characters, mighty struggles, and severe consequences for failure make a brilliant novel.

However, neither science nor magic can support a poorly conceived novel. Science, the supernatural, and magic are just tropes, tools we use to help tell the story. Strong, charismatic characters, mighty struggles, and severe consequences for failure make a brilliant novel.