Over the years, I have learned many tricks to help people get their ideas out of their heads and onto paper.

Nearly everyone says they have an idea for a good story. What separates writers out from the crowd is this: as time passes and they think about it, they write those ideas down. Ninety five percent never get beyond this stage but for a few, thinking about it on paper ends and they dive straight into writing it.

Nearly everyone says they have an idea for a good story. What separates writers out from the crowd is this: as time passes and they think about it, they write those ideas down. Ninety five percent never get beyond this stage but for a few, thinking about it on paper ends and they dive straight into writing it.

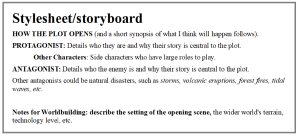

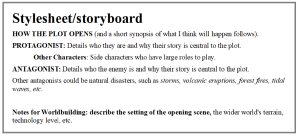

Most will begin without an outline. They are flying blind, or in author speak, “pantsing it.” I am a planner, but I’m also a pantser. I begin with a document that details what I think the story is, a loose outline. I sit somewhere noisy, like a coffee shop or my apartment balcony, and let my mind wander, taking notes as the story comes to me.

When I first began writing, I didn’t know how to construct a story. As time went on and I attended writing classes and seminars, I learned how arcs shape every story, plot arcs, and character arcs. My loose outlines became more detailed. Eventually I began making an Excel workbook as a permanent storyboard/stylesheet for each series.

ANY document or spreadsheet program will work. I think of outlining as pantsing it in advance—a visual aid for when the writing gets real. If I have an idea of how the story should go, I won’t run out of words before the first draft is done.

Once I have the bare bones of the story down on paper, I begin fleshing out each scene. The outline becomes my first draft, and I save it with a new name.

Once that first draft is finished and in revisions, some scenes will make more sense when placed in a different order than originally planned. So, I update the outline with each change. This allows me to view the arc of the story from a distance, so I can see where it might be flatlining.

Sometimes, an event no longer makes sense and no matter how much I love it, I have to cut it. (I always save my outtakes in a separate file for later use.)

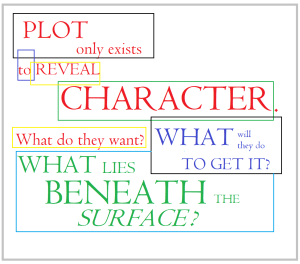

In last week’s post, I went over the questions I ask of each writing project before the words hit the paper. Two important questions are what genre do I think I’m writing in, and what is the underlying theme?

In last week’s post, I went over the questions I ask of each writing project before the words hit the paper. Two important questions are what genre do I think I’m writing in, and what is the underlying theme?

I love reading character-driven fantasy so that is what I write. A world emerges from my imagination along with the characters, and I make notes as bits and pieces of that environment occur to me.

Humor is crucial when you write fantasy that has some dark moments. I have a deep streak of gallows humor that often emerges inappropriately to my family’s regret. Humor in the face of disaster will be a theme. This theme comes out in most of my work.

Next, I create a brief personnel description, less than 100 words for each prominent character. I note the verbs, adjectives, and nouns that describe the character, as those give me all the necessary information. This is just a paragraph, but it contains the essential information.

Sometimes it takes a while to know what a character’s void is (a deep emotional wound), but it will emerge by the time the first draft is done.

The protagonist in the following example doesn’t have a story as she is just an illustration of what I do. But it would be easy to write one for her if I had a few other people figured out.

How I get a story out of my head and onto paper:

What is the core conflict? Is it the Quest for the Magic MacGuffin? Is it a coup followed by a struggle for power? It’s a fantasy, so a wide range of options are open to us.

Who are the players?

Excalibur London_Film_Museum_ via Wikipedia

Valentine (Protagonist) Hates her name and goes by Val. (Arms master, 36. Black hair, brown eyes, suntanned.) VOID: Deep sense of failure. A convergence of bad choices led to a stint in a dungeon. VERBS: Act, fight, build, protect. ADJECTIVES: wary, sarcastic, hopeful, dedicated, considerate. NOUNS: sorrow, guilt, purpose, compassion, wit.

Does Val have close friends? If not, will she gather companions? This question is important. If she doesn’t have friends at first, I will leave space on that page to add them when they emerge from my imagination. As I contemplate Val’s story, perhaps a love interest will show up later, or maybe not.

What happens to take Val out of her comfort zone? Sometimes I don’t have the answer to this for quite a while. Other times, it’s the spark that starts the story.

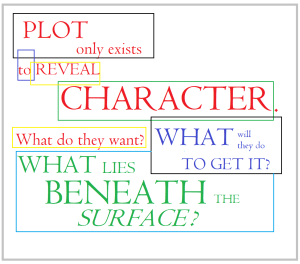

The entire arc of the story rests on how I answer the following question. What is Val’s goal, her deepest desire? Currently, it looks like she’s hoping to regain her self-respect. That will become a secondary quest when a more immediate problem presents itself.

What stands in her way? Who or what is the Enemy?

Let’s name the enemy Kai Voss. What is his deepest desire? How does Kai Voss control the situation at the outset? Once I know who the protagonist is and what they want, I give them the same personnel file I give all the other characters—I identify a void, verbs, adjectives, and nouns for him.

Once I have Kai Voss described in a paragraph, I can determine the quest. Kai Voss is the key to what Val must achieve. A believable villain is why Val’s story will be fun to write.

Later, after I have the characters figured out, I will work on the plot outline and try to shape the story’s arc. This is where roadblocks and obstacles do the heavy lifting, and my outline will contain ideas I can riff on. Val will have to work hard to achieve her goal, but so will Kai Voss.

Information and the lack of it drive the plot. Val can’t have all the information. Kai Voss must have more answers than Val and be ruthless in using that knowledge to achieve his goal. My outline will tell me when it’s time to dole out information. What complications arise from Val’s lack of information?

Information and the lack of it drive the plot. Val can’t have all the information. Kai Voss must have more answers than Val and be ruthless in using that knowledge to achieve his goal. My outline will tell me when it’s time to dole out information. What complications arise from Val’s lack of information?

With each chapter, Val and her companions acquire the necessary information, but each answer leads to more questions. Conflicts occur when Kai Voss sets traps, and by surviving those encounters, Val gains more information about Kai Voss’s capabilities. She must persevere and use that knowledge to win the final battle.

Having my characters in place and an outline helps keep me on track when I am pantsing it through the first draft of a manuscript. New flashes of brilliance will occur as I am writing and will make the struggle real. But two fundamental things will remain constant:

Val’s determination to block Kai Voss and wreck the enemy’s plans is the plot.

Val’s growth as a character as she works her way through the plot is the story.

Next week in part three of this series, we will take a closer look at Val and Kai Voss and see how their strengths and weaknesses drive and help create the overall arc of the plot.

Credits and Attributions:

Excalibur, London Film Museum via Wikipedia

Artist: George Henry Durrie (1820–1863)

Artist: George Henry Durrie (1820–1863)

Title: After the Rain Gloucester

Title: After the Rain Gloucester

![George Henry Durrie [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/george_henry_durrie_-_winter_scene_in_new_haven_connecticut_-_google_art_project.jpg)

![Detail from George Henry Durrie [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/detail_from_george_henry_durrie_-_winter_scene_in_new_haven_connecticut_-_google_art_project.jpg)