Artist: Anders Zorn (1860–1920)

Artist: Anders Zorn (1860–1920)

Title: (Swedish: Sommarnöje) (English: Summer Fun)

Genre: marine art

Date: 1886

Medium: watercolor paint on paper

Dimensions: height: 76 cm (29.9 in)

Collection: Private collection

Place of creation: Dalarö, Sweden

Inscriptions: Signature and date bottom left: Zorn -86

What I love about this painting:

This image, the way the lake is shown, took me back to my childhood. I grew up in a house that faced directly onto a large lake, with a wide beach for swimming, a wooden dock, and few neighbors. The southern Puget Sound area experiences more overcast days in June than most people like. Many days, the waters and the sky looked exactly as Anders Zorn has depicted them here.

Zorn’s brushwork is so meticulous, it is nearly photographic. He captures the feeling of the day, of the breeze, slightly sharp but not too cold, and the anticipation of going out on the water.

About this painting, via Wikipedia:

Zorn painted Sommarnöje in Dalarö in the early summer of 1886, after the couple had returned from honeymoon but before they settled in Mora. He made a smaller sketch first, which measures 30.2 by 18.8 centimeters (11.9 in × 7.4 in), now held by the Zorn Museum in Mora.

The completed watercolor captures a fleeting moment and shows influence from the works of the French Impressionists that Zorn had seen while in Paris, but with a distinctively austere Scandinavian palette.

The painting depicts the artist’s wife Emma Zorn standing in a white dress and hat, waiting on the edge of a wooden pier beside the water, as their friend Carl Gustav Dahlström approaches in a rowing boat.

The reflective glassy surface of the water is rippling in a breeze, under cloudy grey skies. The figures, pier, boat and sea are finely rendered, almost as if the work was made in oil paint, showing Zorn’s skill as a watercolorist. Less attention is paid to the other side of the lake, sketched roughly in the background. It is signed and dated in the lower left corner, “Zorn 86”.

It was acquired by Edvard Levisson of Gothenburg, and then descended through the Schollin-Borg family. The painting was sold at the Stockholms Auktionsverk in June 2010 for SEK 26 million, setting a record for a Swedish painting.

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

Zorn was born in Mora, Sweden, between the lakes of Siljan and Orsasjön. He studied at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts in Stockholm from 1875 to 1880, and then spent time travelling in Europe, painting watercolours and society portraits in London, Paris and Madrid.

He returned to Sweden in 1885, and on 16 October, he married Emma Zorn (née Lamm) (1860 – 1942). After spending their honeymoon abroad, in eastern Europe and Turkey, they returned to Sweden in 1886, spending time with Emma’s family at Dalarö, before settling near Mora, where their house, which is now the home of the Zorn Collections, is located.

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Sommarnöje (1886), akvarell av Anders Zorn.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sommarn%C3%B6je_(1886),_akvarell_av_Anders_Zorn.jpg&oldid=842907051 (accessed February 29, 2024).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Sommarnöje,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Sommarn%C3%B6je&oldid=1149795747 (accessed February 29, 2024).

Then, there’s hunting down and killing the trash and recycling so that we don’t live in a slum, alongside the unlovely side-quest for a clean bathroom. I do these tasks, but they don’t “bring me joy.” I do them so I can get to the good stuff, the best part of the day—which is writing.

Then, there’s hunting down and killing the trash and recycling so that we don’t live in a slum, alongside the unlovely side-quest for a clean bathroom. I do these tasks, but they don’t “bring me joy.” I do them so I can get to the good stuff, the best part of the day—which is writing. Motivations drive emotions, and emotions drive the plot. People have reasons for their actions, and I needed to give my bad guy a good one. Now I know why he must go there.

Motivations drive emotions, and emotions drive the plot. People have reasons for their actions, and I needed to give my bad guy a good one. Now I know why he must go there. Sometimes, the story demands a death, and 99% of the time, it can’t be the protagonist. But death must mean something, wring emotion from us as we write it. Since the characters we have invested most of our time into are the antagonist and protagonist, we must allow a beloved side character to die.

Sometimes, the story demands a death, and 99% of the time, it can’t be the protagonist. But death must mean something, wring emotion from us as we write it. Since the characters we have invested most of our time into are the antagonist and protagonist, we must allow a beloved side character to die. Motivations add fuel to emotions. Emotions drive the scene forward.

Motivations add fuel to emotions. Emotions drive the scene forward. Characters aren’t fully formed when you first lay pen to paper. They evolve as you go, growing out of the experiences you write for them. Sometimes, these changes take the story in an entirely different direction than was planned, which involves a great deal of rewriting. It helps me remain consistent if I note those changes on my outline because then I don’t forget them.

Characters aren’t fully formed when you first lay pen to paper. They evolve as you go, growing out of the experiences you write for them. Sometimes, these changes take the story in an entirely different direction than was planned, which involves a great deal of rewriting. It helps me remain consistent if I note those changes on my outline because then I don’t forget them. I highly recommend the

I highly recommend the  At any gathering of authors, a determined group will proclaim that thoughts should not be italicized under any circumstances. While I disagree with that view, I do see their point.

At any gathering of authors, a determined group will proclaim that thoughts should not be italicized under any circumstances. While I disagree with that view, I do see their point. In a good story, bad things have happened, pushing the characters out of their comfortable rut. They must become creative and work hard to acquire or accomplish their desired goals.

In a good story, bad things have happened, pushing the characters out of their comfortable rut. They must become creative and work hard to acquire or accomplish their desired goals. Artist: Jakub Schikaneder (1855–1924)

Artist: Jakub Schikaneder (1855–1924) Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

Mood is long-term, a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story. Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.

Robert McKee tells us that emotion is the experience of transition, of the characters moving between a state of positivity and negativity.  These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story:

These visuals can easily be shown. Grief manifests in many ways and can become a thread running through the entire narrative. That theme of intense, subliminal emotion is the underlying mood and it shapes the story: This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level.

This is part of the inferential layer, as the audience must infer (deduce) the experience. You can’t tell a reader how to feel. They must experience and understand (infer) what drives the character on a human level. As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere

As we read, the atmosphere that is shown within the pages colors and intensifies our emotions, and at that point, they feel organic. Think about a genuinely gothic tale: the mood and atmosphere  However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

However, there is an accessible viewpoint just at the entrance, and we can go there and just absorb the peace. Several years ago, I shot this photo from that platform.

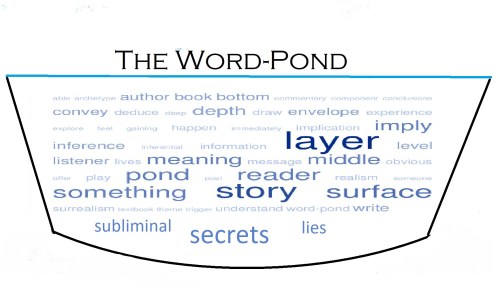

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc.

Action and interaction – we know how the surface of a pond is affected by the breeze that stirs it. In the case of our novel, the breeze that stirs things up is made of motion and emotion. These two elements shape and affect the structural events that form the plot arc. So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world?

So, how can we use the surface elements to convey a message or to poke fun at a social norm? In other words, how can we get our books banned in some parts of this fractured world? Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

Creating depth in our story requires thought and rewriting. The first draft of our novel gives us the surface, the world that is the backdrop.

![Slindebirken, Vinter by Johan Christian Dahl 1838 [Public domain] via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Slindebirken_Vinter_I.C._Dahl.jpg?w=500)

Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. The first reading by an unbiased eye is meant to give the author a view of their story’s overall strengths and weaknesses so that the revision process will go smoothly. This phase should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor. It’s best when the reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel. Also, look for a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. If you are asked to be a beta reader, you should ask several questions of this first draft.

Beta Reading is the first look at a manuscript by someone other than the author. The first reading by an unbiased eye is meant to give the author a view of their story’s overall strengths and weaknesses so that the revision process will go smoothly. This phase should be done before you submit the manuscript to an editor. It’s best when the reader is a person who reads for pleasure and can gently express what they think about a story or novel. Also, look for a person who enjoys the genre of that particular story. If you are asked to be a beta reader, you should ask several questions of this first draft. Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript. A good proofreader understands that the author has already been through the editing gauntlet with that book and is satisfied with it in its current form. A proofreader will not try to hijack the process and derail an author’s launch date by nitpicking their genre, style, and phrasing.

A good proofreader understands that the author has already been through the editing gauntlet with that book and is satisfied with it in its current form. A proofreader will not try to hijack the process and derail an author’s launch date by nitpicking their genre, style, and phrasing.  The problem that frequently rears its head among the Indie community occurs when an author who writes in one genre agrees to proofread the finished product of an author who writes in a different genre. People who write sci-fi or mystery often don’t understand or enjoy paranormal romances, epic fantasy, or YA fantasy.

The problem that frequently rears its head among the Indie community occurs when an author who writes in one genre agrees to proofread the finished product of an author who writes in a different genre. People who write sci-fi or mystery often don’t understand or enjoy paranormal romances, epic fantasy, or YA fantasy. Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These are sneaky and dreadfully difficult to spot. Spell-checker won’t always find them. To you, the author, they make sense because you see what you intended to see. For the reader, they appear as unusually garbled sentences.

Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These are sneaky and dreadfully difficult to spot. Spell-checker won’t always find them. To you, the author, they make sense because you see what you intended to see. For the reader, they appear as unusually garbled sentences. At some point, your manuscript is finished. Your beta readers pointed out areas that needed work. The line editor has beaten you senseless with the

At some point, your manuscript is finished. Your beta readers pointed out areas that needed work. The line editor has beaten you senseless with the  Also, the two combine to help in deciding how long it will take to complete a task.

Also, the two combine to help in deciding how long it will take to complete a task. While I had finished the RPG game’s plot and the synopsis, I didn’t have some details of the universe and the world figured out. So, in a burst of creative predictability, I went astrological in naming the months. I thought it would give the player a feeling of familiarity.

While I had finished the RPG game’s plot and the synopsis, I didn’t have some details of the universe and the world figured out. So, in a burst of creative predictability, I went astrological in naming the months. I thought it would give the player a feeling of familiarity. Time has a tendency to be elastic when we are writing the first draft of a story where many events must occur. Sometimes, many things are accomplished in too short a period for a reader to suspend their disbelief.

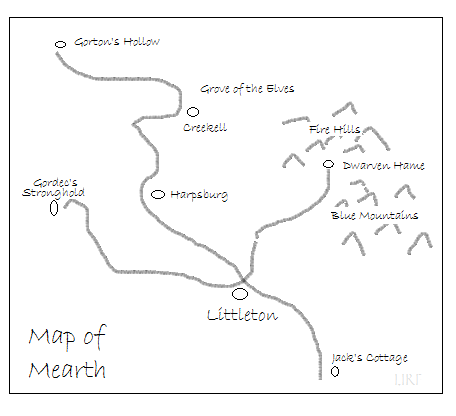

Time has a tendency to be elastic when we are writing the first draft of a story where many events must occur. Sometimes, many things are accomplished in too short a period for a reader to suspend their disbelief. What if your fantasy world uses leagues as a measure of distance? A league is 3.452 miles or 5.556 kilometers. Generally speaking, a horse can walk 32 miles or 51.5 K in a day.

What if your fantasy world uses leagues as a measure of distance? A league is 3.452 miles or 5.556 kilometers. Generally speaking, a horse can walk 32 miles or 51.5 K in a day. Many readers have a route they walk or run daily to maintain their health. These readers will know how long it takes to walk ten blocks. They will also know how far a healthy person can walk in one hour on a good road.

Many readers have a route they walk or run daily to maintain their health. These readers will know how long it takes to walk ten blocks. They will also know how far a healthy person can walk in one hour on a good road. The part of the world where I live has large tracts of forests, many wide rivers, and is mountainous, with numerous volcanos. Our roads are often winding and sometimes travel in switchbacks up and over many of these obstacles. It takes time to go places even though the original road-builders plotted the roads through the most accessible paths.

The part of the world where I live has large tracts of forests, many wide rivers, and is mountainous, with numerous volcanos. Our roads are often winding and sometimes travel in switchbacks up and over many of these obstacles. It takes time to go places even though the original road-builders plotted the roads through the most accessible paths. Travel and events take time. A calendar, either fantasy or the standard Gregorian calendar we use today, and a simple hand-drawn map will help you maintain the logic of your plot.

Travel and events take time. A calendar, either fantasy or the standard Gregorian calendar we use today, and a simple hand-drawn map will help you maintain the logic of your plot.

Author: László Mednyánszky (1852–1919)

Author: László Mednyánszky (1852–1919)