This week we are in Cannon Beach, Oregon, for our annual family pilgrimage. It is the place where sand and sea meet grandchildren and dogs. This year, no toddlers, but one of the older grandchildren is here with his friend.

We booked in January, so we got our favorite condo on the beach. Some years we don’t get it, but we always have fun. My sister-in-law and her husband are in a small house a bit further toward the other end of town. The daughter with the teenagers is staying in the neighboring town of Seaside, which is more oriented to teenagers and caters to their idea of fun.

We booked in January, so we got our favorite condo on the beach. Some years we don’t get it, but we always have fun. My sister-in-law and her husband are in a small house a bit further toward the other end of town. The daughter with the teenagers is staying in the neighboring town of Seaside, which is more oriented to teenagers and caters to their idea of fun.

Cannon Beach is a pleasant village, with flowers in every public place, gardens that are maintained by the city. It’s an attractive tourist town, easily walkable, and with a free transit system.

There is a brewery, several coffee roasters, numerous art galleries, and bookstores. On the main street we find a fabulous wine shop, my all-time favorite bakery, and an old-fashioned candy factory that is to die for.

Most important of all, on the corner near our condo is the grandchildren’s favorite toy store of all time, Geppetto’s. No one can walk past it without stopping in. (Shh – don’t tell anyone, but I’m getting the youngest ones their Christmas presents today.) This store has the most amazing variety of board games and puzzles.

Our condo is in the thick of things, so pizza night is easy to arrange, and a great pub is just around the corner.

We usually stay at the north end of town in the same area every year. I have a full kitchen, essential for the vegan on the road, and can walk out my door to where Ecola Creek enters the sea. The creek is wide here at the estuary but so shallow we can wade across.

The best part of this condo is the lovely gas fireplace for when the teenagers come in dripping seawater and sand, with blue lips and chilled to the bone.

They never listen to Grandma. “Come in before you get hypothermia!”

Just sayin’.

The view from our condo is one that never fails to soothe me. Tillamook Head is just off to the north. A mile out to sea, resting atop a sea stack of basalt, the notorious Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, nicknamed “Terrible Tilly,” has had a long history of strife and tragedy. Although long closed to the public, she still stands today, battered and bruised. Her continued existence is a testament to the quality of construction, as she is much stouter than the rock she was built upon.

About Terrible Tilly, from Wikipedia:

In September 1879, a third survey was ordered, this time headed by John Trewavas, whose experience included the Wolf Rock lighthouse in England. Trewavas was overtaken by large swells and was swept into the sea while attempting a landing, and his body was never recovered. His replacement, Charles A. Ballantyne, had a difficult assignment recruiting workers due to the widespread negative reaction to Trewavas’ death, and a general desire by the public to end the project. Ballantyne was eventually able to secure a group of quarrymen who knew nothing of the tragedy, and was able to resume work on the rock. Transportation to and from the rock involved the use of a derrick line attached with a breeches buoy, and in May 1880, they were able to completely blast the top of the rock to allow the construction of the lighthouse’s foundation.

On October 21, 1934, the original lens was destroyed by a large storm that also leveled parts of the tower railing and greatly damaged the landing platform. Winds had reached 109 miles per hour (175 km/h), launching boulders and debris into the tower, damaging the lantern room and destroying the lens. The derrick and phone lines were destroyed as well. After the storm subsided, communication with the lighthouse was severed until keeper Henry Jenkins built a makeshift radio from the damaged foghorn and telephone to alert officials.

The lighthouse was decommissioned in 1957 and replaced with a whistle buoy, having become the most expensive U.S. lighthouse to operate. During the next twenty years, the lighthouse changed ownership several times; in 1980 a group of realtors purchased the lighthouse and created the Eternity at Sea Columbarium, which opened in June of that year. After interring about 30 urns, the columbarium‘s license was revoked in 1999 by the Oregon Mortuary and Cemetery Board and was rejected upon reapplication in 2005.

Access to the lighthouse is severely limited, with a helicopter landing the only practical way to access the rock, and it is off-limits even to the owners during the seabird nesting season. The structure was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981 and is part of the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge. [1]

I spend a lot of time on the porch, looking out to sea at Terrible Tilly. The view is soothing, although the Northern Pacific waters are wild and untamed.

The lighthouse that I think of as a friend stubbornly clings to life, providing a home for seabirds. I watch it, sitting in solitude and letting my mind go free, and then I write.

When I feel need to clear my mind, I go to the water’s edge and fly my kite. While I do that, my husband roams the beach, watching the seabirds nesting on the God-rock of Cannon Beach, Haystack Rock.

When I feel need to clear my mind, I go to the water’s edge and fly my kite. While I do that, my husband roams the beach, watching the seabirds nesting on the God-rock of Cannon Beach, Haystack Rock.

I will admit, we overindulge in treats reserved only for holidays. On days when we have no grandchildren, we visit our favorite restaurants and pubs. Often we go to a play at the community theater.

Each year, when we return home, my thoughts are clearer for having come to this place of wildness and beauty. I feel invigorated for having spent a week in the company of our loved ones.

Winters on this coast are notoriously awful, as witness the battering of Terrible Tilly, but August is peaceful, with mists rising at dawn, sun all afternoon, and stars falling over the vast ocean.

Every year, the moment we arrive back in our inland valley, I long for this place, my spiritual home. In the days and months to come, this week will shine in my memories, a sliver of paradise outside of the pandemic, a quiet time of rest and rejuvenation.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Tillamook Rock Light,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tillamook_Rock_Light&oldid=1026355176 (accessed August 14, 2021).

All images used in this post are the author’s own work and are copyrighted.

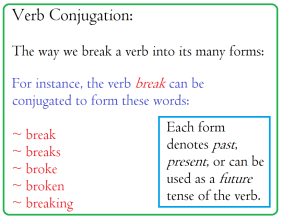

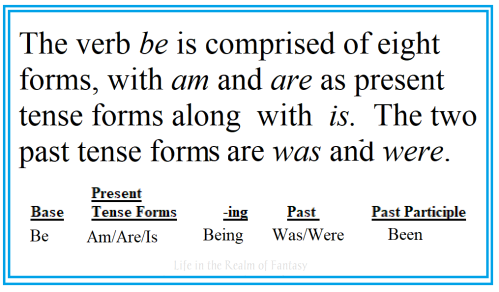

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In  In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go.

In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go. Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view.

Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view. Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.

Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view. Today, we’re focusing on the narrative point of view, discussing who can tell the story most effectively, a protagonist, a sidekick, or an unseen witness.

Today, we’re focusing on the narrative point of view, discussing who can tell the story most effectively, a protagonist, a sidekick, or an unseen witness. Some third-person omniscient modes are also classifiable as “third-person subjective,” modes that switch between the thoughts, feelings, etc. of all the characters.

Some third-person omniscient modes are also classifiable as “third-person subjective,” modes that switch between the thoughts, feelings, etc. of all the characters. The flâneur is the nameless external observer, the interested bystander who reports what they see and overhear about a particular person’s story. They garner their information from the sidewalk, window, garden, or any public place where they commonly observe the protagonists. They are an unreliable narrator, as their biases color their observations. In many of the most famous novels told by the flâneur, the reader comes to care about the unnamed narrator because their prejudices and commentary about the protagonists are endearing.

The flâneur is the nameless external observer, the interested bystander who reports what they see and overhear about a particular person’s story. They garner their information from the sidewalk, window, garden, or any public place where they commonly observe the protagonists. They are an unreliable narrator, as their biases color their observations. In many of the most famous novels told by the flâneur, the reader comes to care about the unnamed narrator because their prejudices and commentary about the protagonists are endearing. Second-person point of view is commonly used in guidebooks and self-help books. It’s also common for do-it-yourself manuals, interactive fiction, role-playing games, gamebooks such as the Choose Your Own Adventure series, musical lyrics, and advertisements.

Second-person point of view is commonly used in guidebooks and self-help books. It’s also common for do-it-yourself manuals, interactive fiction, role-playing games, gamebooks such as the Choose Your Own Adventure series, musical lyrics, and advertisements. I had no intention of writing book one either, but there it is. These characters won’t let go of me, so now I’m storyboarding a new plot.

I had no intention of writing book one either, but there it is. These characters won’t let go of me, so now I’m storyboarding a new plot. Several years ago, I read “

Several years ago, I read “ I had a reaffirmation of sorts; the reassurance that no writer can follow every writing group rule and no book that does would be worth reading.

I had a reaffirmation of sorts; the reassurance that no writer can follow every writing group rule and no book that does would be worth reading. Every successful writer has habits that are technical wrongs, habits that don’t fly when offered to a critique group. Yet, these patterns persist in their work over their career because they are part of that author’s creative process.

Every successful writer has habits that are technical wrongs, habits that don’t fly when offered to a critique group. Yet, these patterns persist in their work over their career because they are part of that author’s creative process. Happiness, anger, spite – all the emotions get a description. Eyebrows raise or draw together; foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble. Lips turn up, lips curve down, and eyes spark – and so on and so on.

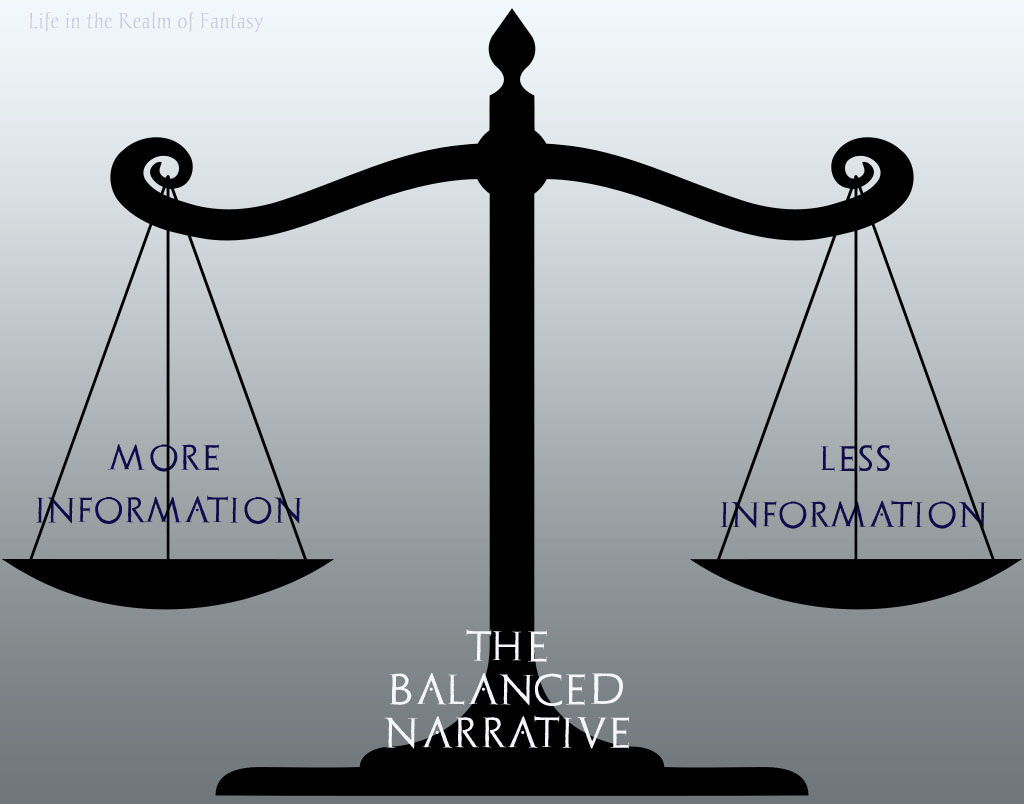

Happiness, anger, spite – all the emotions get a description. Eyebrows raise or draw together; foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble. Lips turn up, lips curve down, and eyes spark – and so on and so on. For me, the most challenging part of writing the final draft of any novel is balancing the visual indicators of emotion with the more profound, internal clues.

For me, the most challenging part of writing the final draft of any novel is balancing the visual indicators of emotion with the more profound, internal clues. I have mentioned

I have mentioned  Open the thesaurus and find words that carry visual impact in your narrative, and you won’t have to resort to a great deal of description.

Open the thesaurus and find words that carry visual impact in your narrative, and you won’t have to resort to a great deal of description. The setting is a coffee shop.

The setting is a coffee shop. First, we want to get to know who we’re writing about.

First, we want to get to know who we’re writing about. Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as stronger than one whose name begins with a soft sound. It’s a little thing but is something to consider when trying to convey personalities.

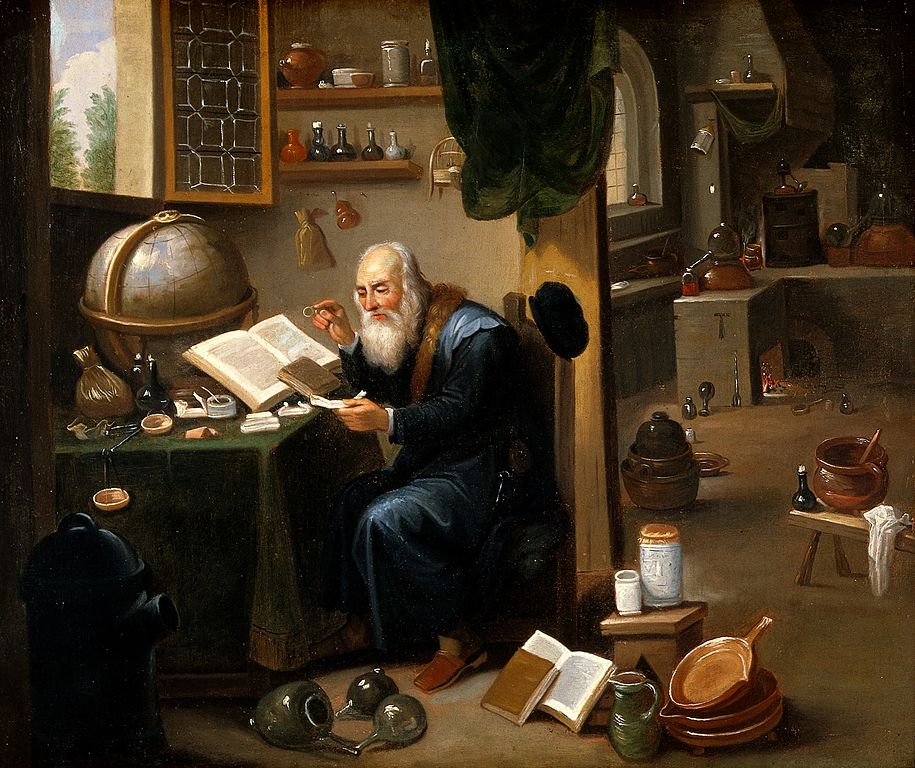

Names say a lot about characters. If you give a character a name that begins with a hard consonant, the reader will subconsciously see them as stronger than one whose name begins with a soft sound. It’s a little thing but is something to consider when trying to convey personalities. Magic and the ability to wield it confers power. Magical creatures, elves, mythical races, mythological gods and demigods – these are some of the many natural and supernatural components of fantasy.

Magic and the ability to wield it confers power. Magical creatures, elves, mythical races, mythological gods and demigods – these are some of the many natural and supernatural components of fantasy. Authors of sci-fi must do the research and understand the

Authors of sci-fi must do the research and understand the  The following is my list of places where the rules of believable magic and technology converge in genre fiction:

The following is my list of places where the rules of believable magic and technology converge in genre fiction: Science or magic is only an underpinning of the plot. They are foundational components of the backstory.

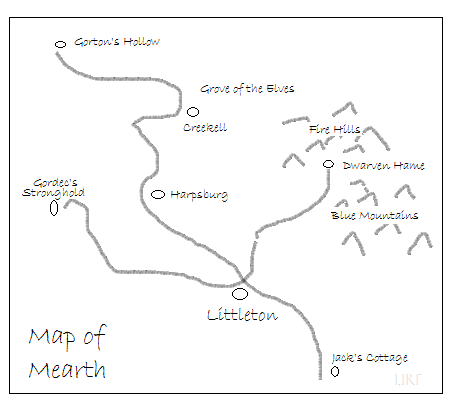

Science or magic is only an underpinning of the plot. They are foundational components of the backstory.  If you are writing a contemporary novel or historical work set in our real world, this is where you keep maps and maybe a link to Google Earth.

If you are writing a contemporary novel or historical work set in our real world, this is where you keep maps and maybe a link to Google Earth. The “three S’s” of worldbuilding are critical: sights, sounds, and smells. Those sensory elements create what we know of the world. Taste rarely comes into it, except when showing an odor.

The “three S’s” of worldbuilding are critical: sights, sounds, and smells. Those sensory elements create what we know of the world. Taste rarely comes into it, except when showing an odor. At this moment, inside your room and outside your door, you have all the elements you need to create an alien or alternate world.

At this moment, inside your room and outside your door, you have all the elements you need to create an alien or alternate world. On June 27th, within the space of days, we went from temperatures well below average, low to mid-60s, and pouring rain to suffering from temperatures well above 100 degrees—108 at my house, 111 at my sister’s house 10 miles away. We use Fahrenheit in the US, but for you in the UK and Europe, we topped out at around 44 degrees Celsius. For more on the week from H**l,

On June 27th, within the space of days, we went from temperatures well below average, low to mid-60s, and pouring rain to suffering from temperatures well above 100 degrees—108 at my house, 111 at my sister’s house 10 miles away. We use Fahrenheit in the US, but for you in the UK and Europe, we topped out at around 44 degrees Celsius. For more on the week from H**l,

The journey from our youngest daughter’s house to our home 60 miles south of there took 3 ½ hours, a trip that should take an hour. Unfortunately, traffic had ground to a halt in many places. At times, we would speed along at 5 miles an hour, sometimes as fast as ten. Many drivers couldn’t handle the 94-degree heat of that day, and their short tempers combined with several stalled vehicles made for a miserable journey down I5.

The journey from our youngest daughter’s house to our home 60 miles south of there took 3 ½ hours, a trip that should take an hour. Unfortunately, traffic had ground to a halt in many places. At times, we would speed along at 5 miles an hour, sometimes as fast as ten. Many drivers couldn’t handle the 94-degree heat of that day, and their short tempers combined with several stalled vehicles made for a miserable journey down I5. STOP! If you value your reputation, you won’t rush to publish that mess just yet.

STOP! If you value your reputation, you won’t rush to publish that mess just yet. Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different.

Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different. At this point, an amateur decides the beta reader missed the point and chooses to ignore their comments. Our unrealistic belief that our work is perfect as it falls from our minds is a failing that we must overcome if we want to engage readers.

At this point, an amateur decides the beta reader missed the point and chooses to ignore their comments. Our unrealistic belief that our work is perfect as it falls from our minds is a failing that we must overcome if we want to engage readers. In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot.

In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot.