No matter the genre, from sci-fi to romance, a mentor shows up to offer needed information that helps the protagonist succeed in their quest. I write fantasy, so certain themes figure prominently in my work. Often, the theme that shapes the main character’s arc is the hero’s journey or, possibly, coming-of-age. These are strong themes, and in stories where the character arc is shaped by them, one of the side characters can serve as a mentor.

The mentor can take many forms. Creating a mentor with depth and a sense of history without going off on a tangent is tricky. This is where my writing group is so helpful. Their thoughts and opinions enable me to narrow the focus, helping me create a character who empowers my intended plot arc, but doesn’t take over the story.

The mentor can take many forms. Creating a mentor with depth and a sense of history without going off on a tangent is tricky. This is where my writing group is so helpful. Their thoughts and opinions enable me to narrow the focus, helping me create a character who empowers my intended plot arc, but doesn’t take over the story.

I often think about the people who guided me when I was young. In my case, my father encouraged me to never stop learning. But the person who had the most influence on my view of family was my maternal grandmother. She was an amazing woman, and I aspire to be the kind of person she was.

She never lectured or preached, but she knew things, and I learned by observing her. She had an Edwardian childhood and a Roaring Twenties adulthood. Family was the most important thing to her.

She never lectured or preached, but she knew things, and I learned by observing her. She had an Edwardian childhood and a Roaring Twenties adulthood. Family was the most important thing to her.

She understood that life is a series of learning from our mistakes but expected us to do what was right. Watching her taught me that true wisdom is not about having all the answers. It is about doing the best you can with what you have and finding joy in the small things.

Wisdom is a word that symbolizes a myriad of ideas. In a mentor, it can signify knowledge of fundamental human truths. Perhaps their naïve enjoyment of life has long gone, but in its place is the ability to enjoy the now, to be truly present in life.

The story will tell you what sort of mentor it requires. Some mentors can provide food and shelter, momentary comfort, and an opportunity to heal and regroup. Through their actions and conversation, these mentors can dispense needed wisdom.

Others are more formal: a leader who trains the protagonist in a craft, such as weaponry or magic, something needed to fulfil the quest.

Experience makes a person wiser and can change the personalities of our characters. Perhaps one becomes hardened as a form of self-preservation. That person can become the Han Solo kind of mentor.

Conversely, life experiences can make a mentor more understanding of human frailty.

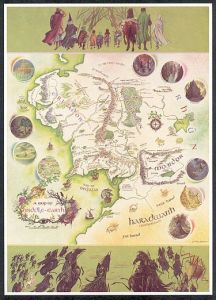

Let’s look at Aragorn, from the Lord of the Rings Trilogy.

Tolkien was crafty. The scene where Aragorn is first introduced makes us wary. The man we meet is mysterious and seems a little dangerous. Yet there is more to him than we see in the dark, smoky taproom of the Prancing Pony, and we wonder about him. At that point, he is only known as Strider, and in that role, he offers them the information they need.

Tolkien was crafty. The scene where Aragorn is first introduced makes us wary. The man we meet is mysterious and seems a little dangerous. Yet there is more to him than we see in the dark, smoky taproom of the Prancing Pony, and we wonder about him. At that point, he is only known as Strider, and in that role, he offers them the information they need.

In the chapter titled “Strider,” Frodo reads Gandalf’s letter. Having read it, Frodo says, “I think one of his (Sauron’s) spies would – well, seem fairer and feel fouler, if you understand.”

“I see,” laughed Strider. “I look foul and feel fair. Is that it? All that is gold does not glitter, not all those who wander are lost.” [1]

In the scene, Aragorn is quoting a poem that is later revealed to reference him and his birthright. These are wise words from a poem-within-the-story, a signature literary device Tolkien used regularly.

“All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.”

With that quote, he cautions Frodo to look beyond the surface and see the strength that lies beneath. He suggests that the converse can be true, that beauty can disguise what is evil.

In Aragorn, we have a mentor who is wise from life experience and somewhat hardened to the discomforts of his exile. But he is also kind, a person who cares about even the smallest people. He is later revealed to be the heir of Isildur, the sole remaining scion of the fabled last King of Gondor.

Yet, at this stage, he is approaching middle age and may as well be heir of nothing. The respectable landlord of the Prancing Pony looks down on him, seeing Aragorn as little more than a vagrant. Here, he is only known as Strider, leader of the Rangers. These soldiers are not merely mercenaries; they are the Dúnedain of the North, the descendants of his ancestor’s knights.

In the guise of Strider, Aragorn is a good mentor from the first moment we meet him. The reader understands this because he is shown to have a history. Tolkien does this perfectly as the backstory is only hinted at.

Frodo knows nothing about him, other than he is a friend of Gandalf. But Frodo has a good sense about people, and something tells him Strider can be trusted. Our protagonist listens to his counsel even when he disagrees with it.

When we create a mentor character, we must give the reader reasons to believe they have the wisdom our protagonist needs.

At the outset, when we find Strider in the Prancing Pony observing Frodo making the worst possible blunder, we know instantly that there is more to this man than is seen on the surface.

“Well? Why did you do that? Worse than anything your friends could have said! You have put your foot in it! Or should I say your finger?” ~ Strider, The Fellowship of the Ring. [1]

In that scene, we meet a person who knows about the secret Frodo carries. Despite Frodo’s error, Tolkien’s portrayal of him makes us believe that he won’t try to steal it, that he is honorable. Here is a person who genuinely wants to help Frodo escape the Black Riders.

In that scene, we meet a person who knows about the secret Frodo carries. Despite Frodo’s error, Tolkien’s portrayal of him makes us believe that he won’t try to steal it, that he is honorable. Here is a person who genuinely wants to help Frodo escape the Black Riders.

We hope that Frodo will listen to him despite his (justifiable) paranoia and Sam’s misgivings.

When I create a mentor in a story, I hope to convey a sense of history without beating the reader over the head with it. I want to evoke a feeling of rightness, that this person knows things we don’t, that this person has knowledge our protagonist must gain.

Hopefully, the insights of my own mentors (my writing group) will guide me to write memorable narratives filled with characters who leave an impact.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Quote from The Fellowship of the Ring, by J.R.R. Tolkien, Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; Illustrated edition, published 29 July 1954. (accessed December 28, 2025) Fair Use.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring theatrical release poster. Wikipedia contributors, “The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring,”Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Lord_of_the_Rings:_The_Fellowship_of_the_Ring&oldid=1329784385(accessed December 28, 2025).

Wikipedia contributors, “The Fellowship of the Ring,”Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Fellowship_of_the_Ring&oldid=1329646864(accessed December 28, 2025).