I always think that in some ways, books are like machines. They’re comprised of many essential components, and if one element fails, the book won’t work the way the author envisions it.

Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation).

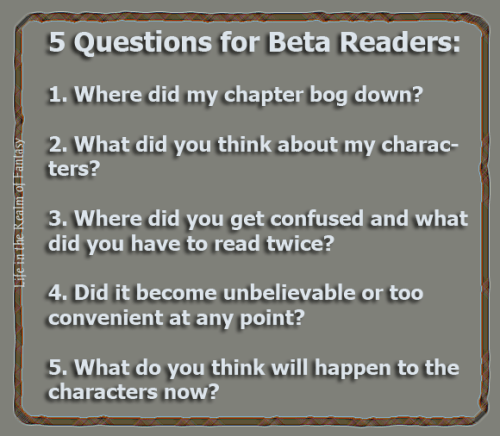

As an editor, I’ve seen every kind of mistake you can imagine, and I have written some travesties myself. I need my writing group, people with a critical eye who see my work first and give me good advice when I’ve gone astray.

I don’t want to waste my editor’s time, so once I have completed the revisions suggested by my beta readers, I begin a self-edit.

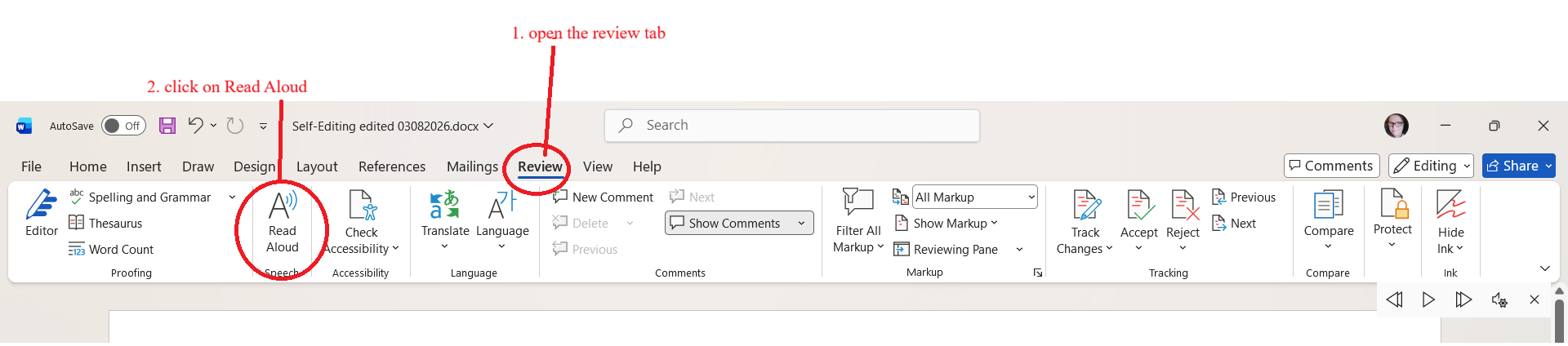

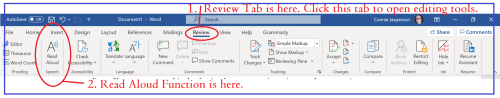

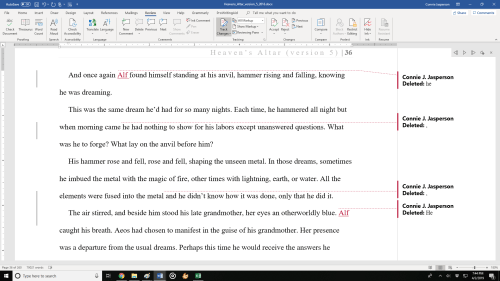

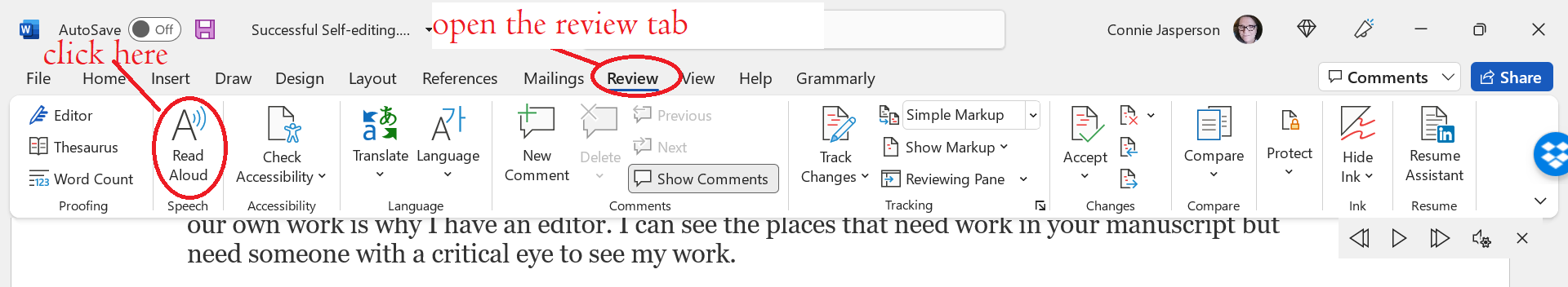

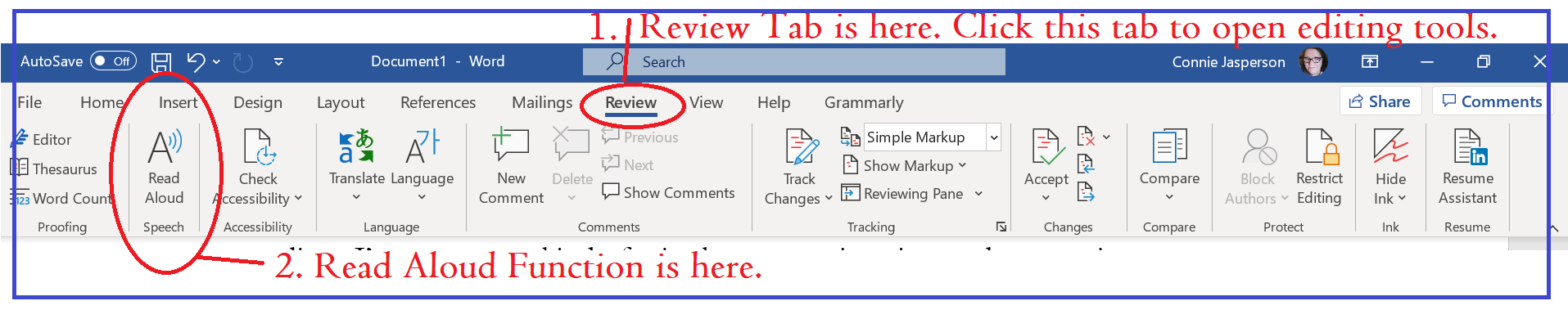

I use Microsoft Word, but most word processing programs have a read-aloud function. I place the cursor where I want to begin and open the Review Tab. Then, I click on Read Aloud and begin reading along with the mechanical voice. Yes, the AI voice can be annoying and doesn’t always pronounce things right, but this first tool shows me a wide variety of places that need rewriting.

I habitually type ‘though’ when I mean ‘through,’ and ‘lighting’ when I mean ‘lightning.’ These are two widely different words but are only one letter apart. Most misspelled words will leap out when you hear them read aloud.

I habitually type ‘though’ when I mean ‘through,’ and ‘lighting’ when I mean ‘lightning.’ These are two widely different words but are only one letter apart. Most misspelled words will leap out when you hear them read aloud.

- Run-on sentences stand out.

- Inadvertent repetitions also stand out.

- Hokey phrasing doesn’t sound as good as you thought it was.

- You notice where words like “the” or “a” before a noun were skipped.

This process involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through the entire 90,000-word manuscript. At the end, I will have trimmed about 3,000 words.

The next phase of this process is where I find and correct punctuation and find more places that need improvement. Sometimes I trim away entire sections, riffs on ideas that have already been presented. Often, they are outright repetitions that don’t leap out on the computer screen. (Those are often cut-and-paste errors.)

The next phase of this process is where I find and correct punctuation and find more places that need improvement. Sometimes I trim away entire sections, riffs on ideas that have already been presented. Often, they are outright repetitions that don’t leap out on the computer screen. (Those are often cut-and-paste errors.)

Open your manuscript. Break it into separate chapters, and make sure each is clearly and consistently labeled. Make certain the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence and that they don’t skip a number. For a work in progress, Baron’s Hollow, I would title the chapter files this way:

- BH_ch_1

- BH_ch_2

- and so on until the end.

Print out the first chapter. Everything looks different printed out, and you will see many things you don’t notice on the computer screen or hear when the AI voice reads it aloud.

- Turn to the last page. Cover the page with another sheet of paper, leaving only the last paragraph visible.

- Starting with the last paragraph on the last page, begin reading, working your way forward.

- Use a yellow highlighter to mark each place that needs correction.

- Put the corrected chapter on a recipe stand next to your computer. Open your document and begin making revisions as noted on your hard copy.

Repeat this process with each chapter.

This is the phase where I look for what I think of as code words. I look at words like “went.” In my personal writing habits, “went” is a code word that tells me when a scene ends and transitions to another stage. The characters or their circumstances are undergoing a change. One scene is ending, and another is beginning.

Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals that tell me what I intend the scene to be. In the rewrite, I must expand on those ideas and ensure the prose is active. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals that tell me what I intend the scene to be. In the rewrite, I must expand on those ideas and ensure the prose is active. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

Let’s look at the word “went.” When I see it, I immediately know someone is going somewhere.

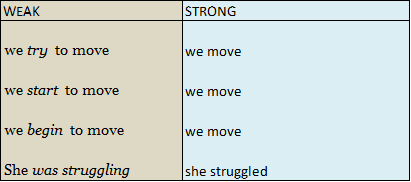

But in many contexts, “went” is a telling word and can lead to passive phrasing.

Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the author’s part, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.

I ask myself, “How do they go?” Went can always be shown as a brief, one-sentence scene. James opened the door and strode out.

Confusing passages stand out when you see them printed. Maybe it’s the opposite of an info dump. Maybe the lead-up to the scene wasn’t shown well enough and leaves the reader wondering how such a thing happened.

The most confusing places are often sections where I cut a sentence or paragraph and moved it to a different place. These really stand out if they create a garbled scene.

HINT: If your eye wants to skip over a section of the printout, STOP. Read that section aloud and discover why your mind wants to skip it. Was it too wordy? Was it muddled? Something made your eye want to skip it and you need to discover why.

HINT: If your eye wants to skip over a section of the printout, STOP. Read that section aloud and discover why your mind wants to skip it. Was it too wordy? Was it muddled? Something made your eye want to skip it and you need to discover why.

By the end of phase two, I will have trimmed about 3,000 more words from my manuscript.

At this point, the manuscript might look finished, but it has only just begun the journey. Now it is as ready as I can make it, and it goes to my editor, Irene, who gives it the final polish.

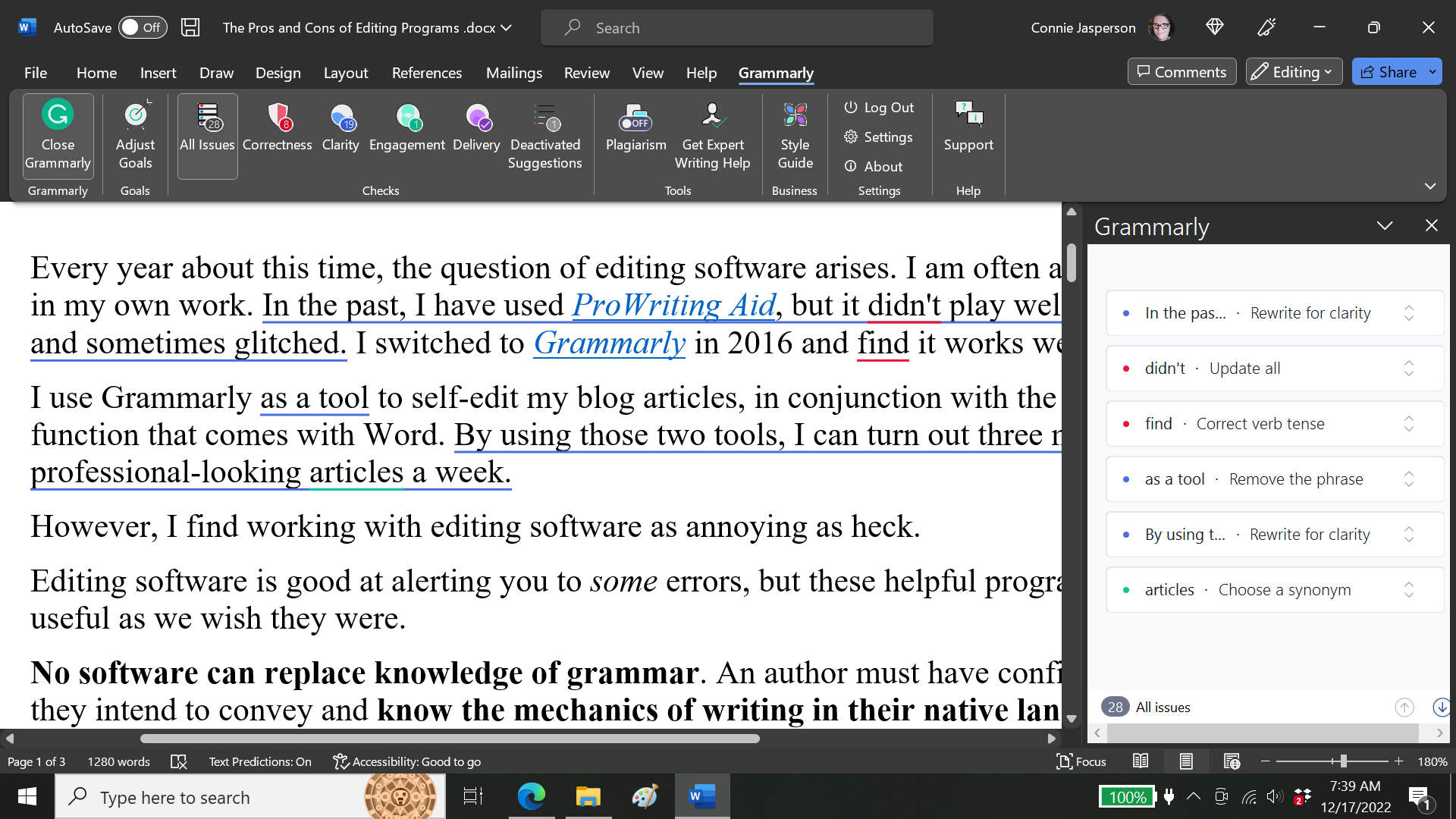

Context is everything. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible comma and spelling malfunctions.

If you don’t know anything about punctuation, don’t feel alone. Most of us don’t when we’re first starting out, but we learn by looking things up and practicing.

If you are looking for a simple guide to commas that will cost you nothing, check out my post, Fundamentals of Grammar: 7 basic rules of punctuation, published here July 7, 2021.

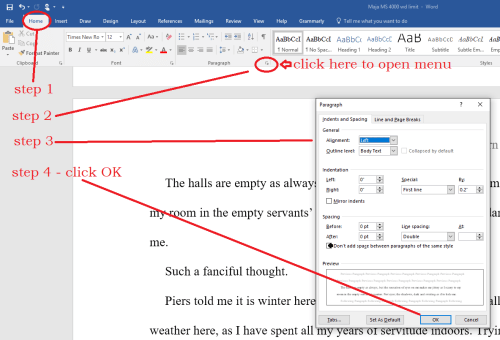

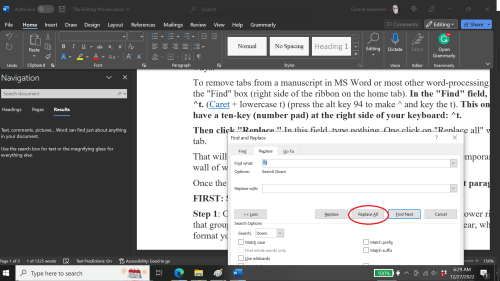

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used.

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used. Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey.

Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey. The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

I am wary of relying on

I am wary of relying on  If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file. I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them. If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in  Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

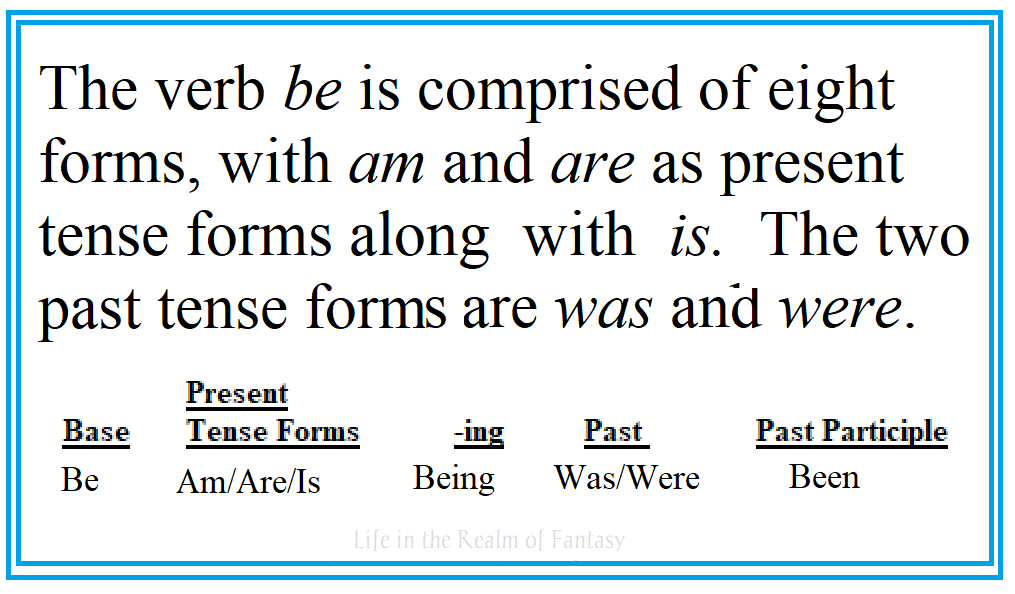

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice. Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals. So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like

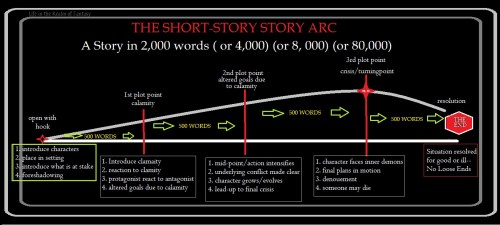

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like  The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it?

The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it? Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen.

Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen. Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year. This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions.

This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions. When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t.

When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t. Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first.

Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first. Here are a few things that stand out when I do this:

Here are a few things that stand out when I do this: If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be.

If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be. The publishing world is a rough playground. Editors for traditional publishing companies and small presses have a landslide of work to pick from and are chronically short-staffed. They can’t accept unprofessional work regardless of how good the story is.

The publishing world is a rough playground. Editors for traditional publishing companies and small presses have a landslide of work to pick from and are chronically short-staffed. They can’t accept unprofessional work regardless of how good the story is. Before you hire an editor, check their qualifications and references.

Before you hire an editor, check their qualifications and references.

If you’re a member of a writers’ group, you have a resource of people who will beta read for you at no cost. As a critique group member, you will read for them too.

If you’re a member of a writers’ group, you have a resource of people who will beta read for you at no cost. As a critique group member, you will read for them too. Clearly and consistently label each chapter. Ensure the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence, and don’t skip a number. I would label my individual chapter files this way:

Clearly and consistently label each chapter. Ensure the chapter numbers are in the proper sequence, and don’t skip a number. I would label my individual chapter files this way: If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

I understand that slight incompatibility has been resolved. In my opinion, both programs are good, and both have pros and cons.

I understand that slight incompatibility has been resolved. In my opinion, both programs are good, and both have pros and cons. Most word processing programs have some form of spellcheck and some minor editing assists. Spellcheck is notorious for both helping and hindering you.

Most word processing programs have some form of spellcheck and some minor editing assists. Spellcheck is notorious for both helping and hindering you. You might disagree with the program’s suggestions. You, the author, have control and can disregard suggested changes if they make no sense. I regularly reject weird suggestions.

You might disagree with the program’s suggestions. You, the author, have control and can disregard suggested changes if they make no sense. I regularly reject weird suggestions. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. Also, it never hurts to have a book of synonyms on hand. We all tend to inadvertently repeat ourselves, and the Read Aloud function will shed light on those crutch words. A dictionary of synonyms and antonyms can help us find good alternatives.

Also, it never hurts to have a book of synonyms on hand. We all tend to inadvertently repeat ourselves, and the Read Aloud function will shed light on those crutch words. A dictionary of synonyms and antonyms can help us find good alternatives.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it.

In some ways, novels are machines. Internally, each book is comprised of many essential components. If one element fails, the story won’t work the way I envision it. So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection.

So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection. I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

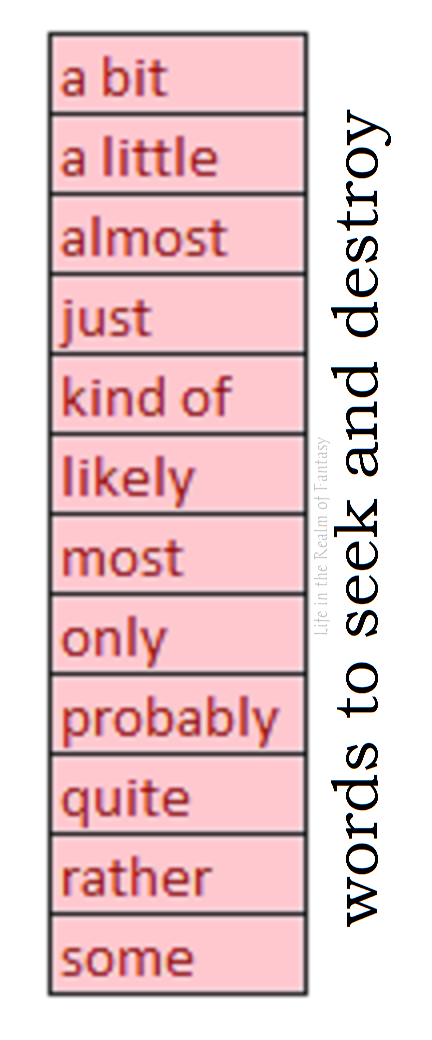

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination. Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error.

Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error. Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later.

Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later. Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation).

Prose, plot, transitions, pacing, theme, characterization, dialogue, and mechanics (grammar/punctuation). I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This phase is where I find my punctuation errors most often. I look for and correct punctuation and make notes for any other improvements that must be made. Usually, I cut entire sections, as they are riffs on ideas that have been presented before. Sometimes they are outright repetitions, which don’t leap out when viewed on the computer screen.

This phase is where I find my punctuation errors most often. I look for and correct punctuation and make notes for any other improvements that must be made. Usually, I cut entire sections, as they are riffs on ideas that have been presented before. Sometimes they are outright repetitions, which don’t leap out when viewed on the computer screen. Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the part of the author, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.

Passive phrasing does the job with little effort on the part of the author, which is why the first drafts of my work are littered with it. Active phrasing takes more effort because it involves visualizing a scene and showing it to the reader.