In life we often find ourselves boxed into a corner, frantically dealing with things we could have avoided if only we had paid attention and not ignored the metaphoric “turn back now” signs.

In life we often find ourselves boxed into a corner, frantically dealing with things we could have avoided if only we had paid attention and not ignored the metaphoric “turn back now” signs.

Imagine a road trip where you are sent off on a detour in a city you’re unfamiliar with. Imagine what would happen if some of the signs were missing, detour signs telling you the correct way to go, and also a one-way street warning sign.

At some point before you realized the signs had been removed, there was a place you could have turned back. Unaware of the danger, you passed that stopping point by and turned left when you should have turned right, and found yourself driving into oncoming traffic on a one-way street.

That safe place where you could have turned around before you entered the danger zone was the point of no return for your adventure. Fortunately, in our hypothetical road-trip no one was harmed, although you were honked at and verbally abused by the people who were endangered by your wrong turn. You made it safely out danger, but you’ll never take a detour again without fearing the worst.

In literature what is the point of no return? Scott Driscoll, on his blog, says, “This event or act represents the point of maximum risk and exposure for the main character (and precedes the crisis moment and climax).”

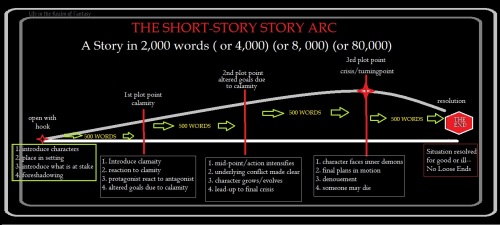

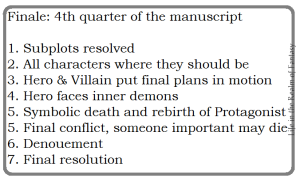

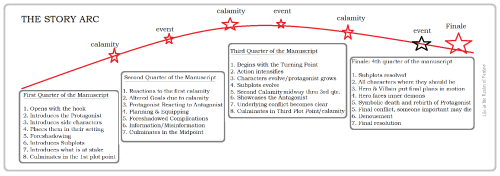

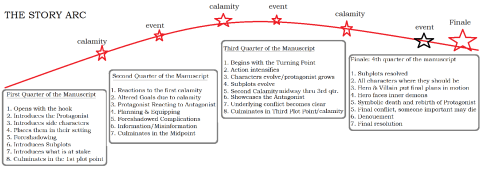

Epic fantasy, which is what the novels in my Tower of Bones series are, generally features a plot driven by a chain of events, small points of no return, each one progressively forcing the protagonist and his/her companions to their meeting with destiny. These scenes of action form arcs that rise to the Third Plot Point: the event that is either an actual death or a symbolic death, but which forces the hero/heroine to be greater than they believed they could be.

For me, in a gripping story, the struggle may have been fraught with hardship, but the actual point of no return is the event that forces the ultimate showdown and face-to-face confrontation with the enemy.

What if you aren’t writing epic fantasy? This series of “arcs of action” driving the plot comes into play in every novel to some degree—the protagonists are in danger of losing everything because they didn’t recognize the warning signs, and they are pushed to the final confrontation whether they are ready for it or not.

During the build-up to the point of no return, you must develop your characters’ strengths. Identify the protagonist’s goals early on, and clarify why he/she must struggle to achieve them.

- How does the hero react to being thwarted in his efforts?

- How does the villain currently control the situation?

- How does the hero react to pressure from the villain?

- How does the struggle deepen the relationships between the hero and his cohorts/romantic interest?

- What complications (for the hero) arise from a lack of information regarding the conflict, and how will he/she acquire that necessary information?

Calamity and struggle create opportunities for your character to grow, so it is your task to litter your protagonist’s path with obstacles that stretch his/her abilities and which are believable. Each time he/she overcomes a hair-raising obstruction, the reader is rewarded with a feeling of satisfaction.

Calamity and struggle create opportunities for your character to grow, so it is your task to litter your protagonist’s path with obstacles that stretch his/her abilities and which are believable. Each time he/she overcomes a hair-raising obstruction, the reader is rewarded with a feeling of satisfaction.

It doesn’t matter what genre you are writing in: you could be writing romances, thrillers, paranormal fantasy, or contemporary women’s lit—for all fiction, obstacles in the protagonist’s path make for satisfying conclusions. I say this because the books I love to read the most are crafted in such a way that we get to know the characters, see them in their environment, and …uh ohh…. Calamity happens, thrusting the hero down the road to divorce court, or trying to head off a nuclear melt-down. Sometimes our hero finds himself walking to Naglimund, or to the Misty Mountains with nothing but the clothes on his back.

Calamity is the fertile ground from which adventure springs, and most calamities are preceded by a point of no return. Identify this plot point, and make it subtly clear to the reader, even if only in hindsight.

![Claude Monet Painting in his Garden, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/pierre-auguste-renoir-claude-monet-painting-in-his-garden.jpg?w=300&h=244)