Passive writing occurs when, as storytellers, we are separated from the moment by words that block our intimacy with the action. Beginning writers often choose stative verbs, the passive voice, and heavily depend on weak verb forms in their writing.

One step on the slippery slope of passive prose is the overuse of stative verbs. Stative verbs express a state rather than an action.

One step on the slippery slope of passive prose is the overuse of stative verbs. Stative verbs express a state rather than an action.

They are “telling” words.

A few Stative Verbs as listed by Ginger Software:

adore

agree

appear (seem)

appreciate

be (exist)

believe

belong to

For a more comprehensive list of stative verbs, go to this article: Stative Verbs – List of Stative Verbs & Exercises | Ginger (gingersoftware.com). [1]

Let’s get real—at times, stative verbs are necessary to a balanced prose. We want a narrative that expresses the human condition, and how we feel at a given moment is often part of that story. But we must balance a little telling with far more showing.

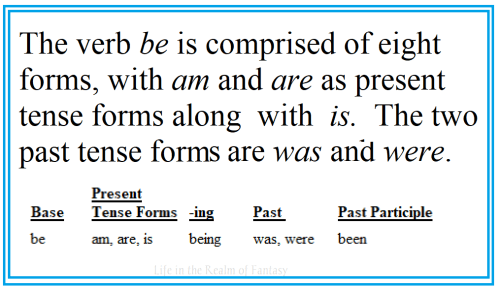

When we are first starting in the craft, we lean heavily on subjunctives and the irrealis forms of mood words. Subjunctive verbs and all forms of the verb be are hard to spot in our own work.

I think the habit of using one of the eight forms of the word be is more one of nurture, not nature. When we first start out in this craft, we tend to write weak sentences. This is because we are trained as children to tell what happened.

I think the habit of using one of the eight forms of the word be is more one of nurture, not nature. When we first start out in this craft, we tend to write weak sentences. This is because we are trained as children to tell what happened.

Writers often find the words and rules we use to describe existence convoluted and hard to understand.

The subjunctive (in the English language) is used to form sentences that do not describe known objective facts. These are words noting or pertaining to a mood or mode of a verb.

In grammar, mood and mode refer to verb forms. That mood or mode depends on how the clause the verbs are contained in relates to the speaker’s or writer’s wishes, intention, or claims about reality.

These verbs may be used for subjective, doubtful, hypothetical, or grammatically subordinate statements or questions. An example is the mood of the verb ‘be’ in ‘if this be treason.’

In other words, subjunctives describe unknown intangible possibilities.

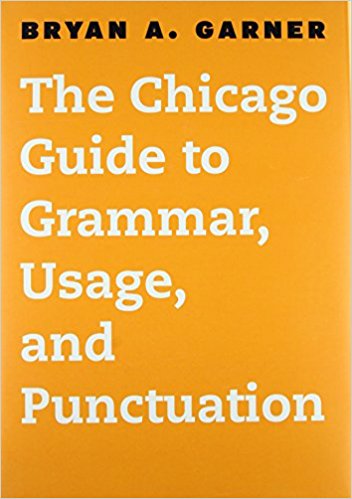

The whole thing looks quite complicated on the surface, but it doesn’t have to be. We must begin assembling our writers’ toolbox. One important tool is Bryan Garner’s The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation (Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing).

The whole thing looks quite complicated on the surface, but it doesn’t have to be. We must begin assembling our writers’ toolbox. One important tool is Bryan Garner’s The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation (Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing).

This is the book that will show you how to write a properly punctuated and formed sentence. It explains what a paragraph is and shows how to connect those sentences into understandable chunks of prose. The book also shows how to write and punctuate dialogue so that our work looks professional.

Soon, we have written a story and other people enjoy reading it.

In our first draft, we tell the story as if it were an event that we witnessed only a few moments before. Everything in our mind occurs in real-time, but once visualized, it becomes a memory. We tend to express our scenes and events as having a state of being, but we are looking back at them from a few moments in the future. So, the narrative is rife with they were, or it was.

We all start out writing that way, but with practice and self-education, we learn to write active prose. We begin by paying attention to our verb forms in the revision process.

I don’t have an education in journalism, yet I choose to write. Most of my friends who are authors don’t have degrees in either journalism or literature. So, if we wish to gain strength as authors, we must educate ourselves.

Learning the craft of writing is like learning the craft of carpentry. If you want to craft beautiful work, you must own the proper tools for the job and learn how to use them. My toolbox contains:

- MS Word as my word-processing program. You may prefer a different program.

- The Chicago Manual of Style (for editing work in American English).

- The Oxford A-Z of Grammar & Punctuation (for editing work in UK English).

- Trusted, knowledgeable beta-readers for my own work.

- Books on how to craft a story/novel.

- Having my work edited by good, well-recommended editors.

- Taking free online writing classes.

- Regularly attending seminars (not free, but worth the money).

- Meeting with my weekly writing group (virtual meetings).

- Daily reading in ALL genres.

- Attending NaNoWriMo Write-Ins (virtual meetings).

What is in your toolbox? It takes a little effort, but you can educate yourself for free if you have the internet. You can learn how to express your ideas so that other people will enjoy them.

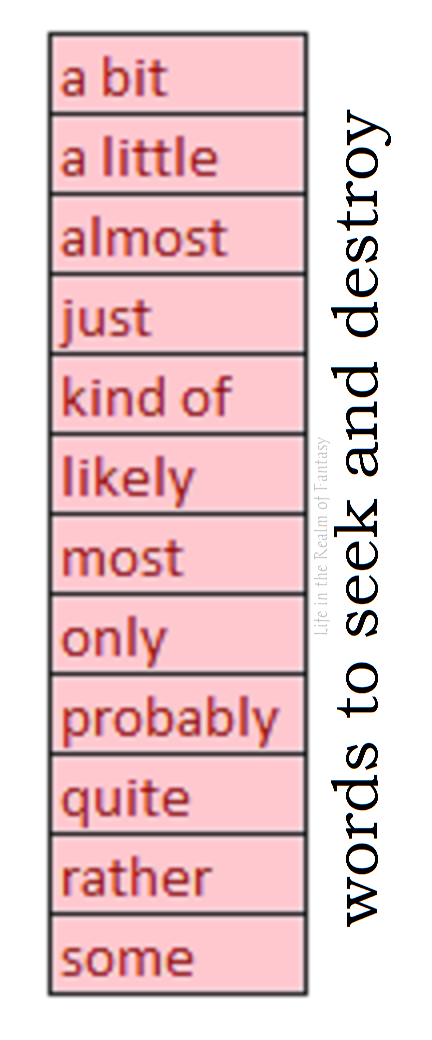

One step is to identify the habitual overuse of the Subjunctive Mood in your writing. Cut back on subjunctives and see how your prose improves.

I say cut back, not eliminate. Despite the misguided efforts of many gurus and Microsoft Word to erase all forms of ‘to be’ from the English language and replace it with ‘is,’ there are times when only a subjunctive will do the job.

I say cut back, not eliminate. Despite the misguided efforts of many gurus and Microsoft Word to erase all forms of ‘to be’ from the English language and replace it with ‘is,’ there are times when only a subjunctive will do the job.

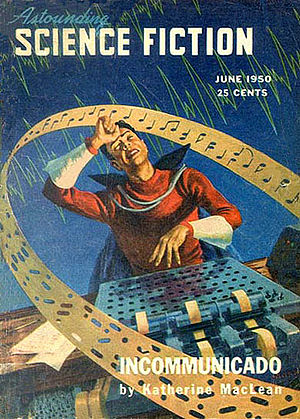

One of the best ways to grow in the craft is to write short stories and send them off. Sometimes they are rejected, and sometimes not. Some stories aren’t really novel material, but maybe they are novellas. Send them to publications and expect rejection because that is how it often is. I can’t tell you how many rejections I have received over the years.

The truth is, we learn more from the rejections than we do the acceptances.

Rejection happens because at first, we write with WAY too many words. But a good writing group will both teach and support you through kind but honest critiques. I find it comforting to know my fellow authors will not tell me my work is awesome if it stinks like Bubba’s socks.

A critique group may tear your work apart, which stings a wounded ego. But we grow from this experience. We learn that opinions are subjective, and writers are thin-skinned creatures. We develop a thicker skin and muck on.

A critique group may tear your work apart, which stings a wounded ego. But we grow from this experience. We learn that opinions are subjective, and writers are thin-skinned creatures. We develop a thicker skin and muck on.

In the revision process, we write mindfully, intentionally crafting lean, powerful prose.

It takes a lot of work to rise from apprentice to journeyman to master in any craft. I don’t know if I will ever achieve that status as an author, but I will keep working and learning. And above all, I will keep reading and will never stop writing.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Quote from Stative Verbs – List of Stative Verbs & Exercises | Ginger (gingersoftware.com) Copyright 2021 Ginger Software.

By creating small arcs in the form of scenes, we offer the reader the chance to experience the rise and fall of tension, the life-breath of the novel.

By creating small arcs in the form of scenes, we offer the reader the chance to experience the rise and fall of tension, the life-breath of the novel. Code words are the author’s first draft

Code words are the author’s first draft  Thought (Introspection):

Thought (Introspection): That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.

That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see. In my last post, I talked about the good and bad aspects of two editing programs that I am familiar with, the things they do and don’t help us identify in our work. One more thing these wonderful programs can’t help us with is identifying bloated backstory.

In my last post, I talked about the good and bad aspects of two editing programs that I am familiar with, the things they do and don’t help us identify in our work. One more thing these wonderful programs can’t help us with is identifying bloated backstory. Look at the first scene of your manuscript. Ask yourself three questions.

Look at the first scene of your manuscript. Ask yourself three questions. I look at each conversation and assess how many words are devoted to each character’s statement and response. Then, when I come to a passage that is inching toward a monologue, I ask myself, “what can be cut that won’t affect the flow of the story or gut the logic of the plot?”

I look at each conversation and assess how many words are devoted to each character’s statement and response. Then, when I come to a passage that is inching toward a monologue, I ask myself, “what can be cut that won’t affect the flow of the story or gut the logic of the plot?” I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t.

I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t. Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error.

Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error. New writers should invest in the

New writers should invest in the  Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later.

Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later. If you have decided something is a “crutch word,” examine the context. Inadvertent repetitions of certain words are easy to eliminate once we see them with a fresh eye.

If you have decided something is a “crutch word,” examine the context. Inadvertent repetitions of certain words are easy to eliminate once we see them with a fresh eye. From my earliest childhood, I always thought of myself as a writer. I just didn’t know how to write anything longer than a poem or a song in such a way that it was readable.

From my earliest childhood, I always thought of myself as a writer. I just didn’t know how to write anything longer than a poem or a song in such a way that it was readable. One day in 1990, I stumbled upon a book offered in the

One day in 1990, I stumbled upon a book offered in the  Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining The Pacific Northwest Writers Association and going to their conferences.

Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining The Pacific Northwest Writers Association and going to their conferences. Six: My final suggestion is this: even though you are writing that novel, keep writing short stories too.

Six: My final suggestion is this: even though you are writing that novel, keep writing short stories too. Events occur, disturbing my writing schedule, but I usually forgive the perpetrators and allow them to live. At that point, I revert to writing whenever I have a free moment.

Events occur, disturbing my writing schedule, but I usually forgive the perpetrators and allow them to live. At that point, I revert to writing whenever I have a free moment. As I have said many times before, being a writer is to be supremely selfish about every aspect of life, including family time.

As I have said many times before, being a writer is to be supremely selfish about every aspect of life, including family time.