When we put the first words of a story on paper, the images and events we imagine as we write have the power to move us. Because we see each scene fully formed in our minds, we are under the illusion that what we have written conveys to a reader the same power that moved us. Once we’ve written “the end” it requires no further effort, right?

I don’t know about your work, but usually, at that stage my manuscript reads like a laundry list.

The trick is to understand that, while the first draft has many passages that shine, more of what we have written is only promising. The first draft contains the seeds of what we believe we have written. Like a sculptor, we must work to shave away the detritus and reveal the truth of the narrative.

The trick is to understand that, while the first draft has many passages that shine, more of what we have written is only promising. The first draft contains the seeds of what we believe we have written. Like a sculptor, we must work to shave away the detritus and reveal the truth of the narrative.

One way we do this is by injecting subtly descriptive prose into our narrative. Properly deployed, power words can be subtle and serve as descriptors, yet don’t tell the reader what to feel.

Think of them like falling leaves in autumn. On their own, they weigh nothing, feel like nothing. Put those leaves in a pile, and they have weight. When we incorporate subtle descriptors into the narrative, they come together to convey a sense of depth.

These are words that convey an emotional barrage in a succinct packet.

Let’s consider a story where we want to convey a sense of danger, without saying “it was dangerous.” What we must do is find words that shade the atmosphere toward fear.

Power words can be found beginning with every letter of the alphabet. What are some “B” words that convey a hint of danger, but aren’t “telling” words?

Backlash

Blinded

Blood

Blunder

When you incorporate any of the above “B” words into your prose, you are posting a road sign for the reader, a notice that “ahead lies danger.” Mingle them with other power words, and you have an air of danger.

As authors, it is our job to convey a picture of events.

But words sometimes fail us.

The best resource you can have in your personal library is a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms. Your word processing program may offer you some synonyms when you right click on a word. However, to develop a wide vocabulary of commonly understood words, you should try to find a book like the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms.

The best resource you can have in your personal library is a dictionary of synonyms and antonyms. Your word processing program may offer you some synonyms when you right click on a word. However, to develop a wide vocabulary of commonly understood words, you should try to find a book like the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms.

It’s important to keep your word choices recognizable, not too obscure. When a reader must stop and look up words too frequently, they will feel like you are talking over their head.

Even so, readers like it when you assume they are intelligent and aren’t afraid to use a variety of words. Yes, sometimes one must use technical terms, but I appreciate authors who assume the reader is new to the terminology and offer us a meaning.

Sprinkling your prose with obscure, technical, or pretentious words is not a good idea. As a reader, I find it frustrating to have to stop and look up big words too frequently.

Let’s look at the emotion of discontent. How can it affect the mood of a piece? What words can we incorporate to shape the mood of the narrative to reinforce a character’s growing dissatisfaction? A few words that most people know might be:

Aggression

Awkward

Corrupt

Denigrate

Disparage

Disgust

Irritate

Obnoxious

Pollute

Pompous

Pretentious

Revile

How we incorporate words of all varieties into our prose is up to each of us. We all sound different when we speak aloud, and the same is true for our writing voice. We can tell the story using any mode we choose but the first line of any piece must let the reader know what they are in for.

I meant to run away today.

If that were the opening line of a short story, I would continue reading. Two words, run away, hit hard in this context, feeling a little shocking as an opener. The protagonist is the narrator and is speaking directly to us, which is a bold choice. Right away, you hope you are in for something out of the ordinary.

That line shows intention, implies a situation that is unbearable, and offers us a hint of the personality of the narrator. Who are they, and what is so unbearable?

Here are lines from a different type of story, one told from a third person point of view:

The battered chair creaked as Aengus sat back. “So, what’s your plan then? Are we going to walk up to his front door and say, ‘Hello. We’re here to kill you’?”

This is a conversation, but it shows intention, environment, and personality. Battered is a power word, and so is creaked.

And here is one final scene, one told from a close third person point of view and showing yet another way to incorporate subtle power words into the prose:

Sera saw the vine-covered ruins of Barlow as an allegory of her past. A part of her past had been burned away. She’d been destroyed but was coming back to life in ways she’d never foreseen.

The power words are: ruins, burned away, destroyed. The stories we write come from deep within us. Words sometimes fail us and we lean too heavily on one word that says what we mean. This is hard for us to spot in our own work, but if you set it aside, you may notice repetitious prose.

A friend of mine uses word clouds to show her crutch words. In a word cloud, the larger the word, the more often it appears in the text. Since I am notoriously short on words, let’s see how this post looks as a word cloud.

It came out surprisingly colorful!

One of the best ways to learn about the craft of writing is to talk with other authors. We all have different ways of creating our work, so hearing how another author works always gives me new ideas.

One of the best ways to learn about the craft of writing is to talk with other authors. We all have different ways of creating our work, so hearing how another author works always gives me new ideas. EKR: Mitchell and Mark are a gay couple, but I didn’t want to write them as caricatures. I spent a great deal of time trying out descriptions to come up with two men who are individuals in their own right but collectively a pair who would rattle the conservative county commissioner.

EKR: Mitchell and Mark are a gay couple, but I didn’t want to write them as caricatures. I spent a great deal of time trying out descriptions to come up with two men who are individuals in their own right but collectively a pair who would rattle the conservative county commissioner. CJJ:

CJJ:

Some scenes have no dialogue, are comprised of the actions that propel the plot forward. But often, conversations are the core of the passage, propelling the story onward to the launching point for the next act.

Some scenes have no dialogue, are comprised of the actions that propel the plot forward. But often, conversations are the core of the passage, propelling the story onward to the launching point for the next act. This pertains to the thoughts of your characters too.

This pertains to the thoughts of your characters too. I have said this before, but it bears mentioning again: Never resort to writing foreign languages using Google Translate (or any other translation app). Also, please don’t go nuts writing out foreign accents. It’s frustrating for readers to try to untangle garbled dialogue. A word or two, used consistently, is all that is needed to convey foreignness.

I have said this before, but it bears mentioning again: Never resort to writing foreign languages using Google Translate (or any other translation app). Also, please don’t go nuts writing out foreign accents. It’s frustrating for readers to try to untangle garbled dialogue. A word or two, used consistently, is all that is needed to convey foreignness. To achieve a sense of depth, we begin with simplicity. Each character’s sub-story must be built upon who these characters think they are.

To achieve a sense of depth, we begin with simplicity. Each character’s sub-story must be built upon who these characters think they are. They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth.

They might think one thing about themselves, but this verb is the truth. Knowing the verb (action word) and the noun (object of the action) that best represented my characters made writing

Knowing the verb (action word) and the noun (object of the action) that best represented my characters made writing  STOP! If you value your reputation, you won’t rush to publish that mess just yet.

STOP! If you value your reputation, you won’t rush to publish that mess just yet. Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different.

Now you must set it aside, as you must gain a little distance from it to see it with a clear eye. This is where I seek an outside opinion on the strengths and weaknesses of my proto-novel. I am fortunate to have a local writing group of highly talented published authors. I also trade services with several editors. When the first draft of my manuscript is finished, I send it to a reader. While they are reading it, I work on something completely different. At this point, an amateur decides the beta reader missed the point and chooses to ignore their comments. Our unrealistic belief that our work is perfect as it falls from our minds is a failing that we must overcome if we want to engage readers.

At this point, an amateur decides the beta reader missed the point and chooses to ignore their comments. Our unrealistic belief that our work is perfect as it falls from our minds is a failing that we must overcome if we want to engage readers. In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot.

In my current work, the thoughts and motives of the characters are critical to the midpoint event and subsequent crisis of faith. Yes, who these people are, and their place in the story at the point where we meet them is crucial to the plot. Then there is the marketing of the finished product, but that is NOT my area strength, so I won’t offer any advice on that score.

Then there is the marketing of the finished product, but that is NOT my area strength, so I won’t offer any advice on that score. If you are writing in US English, I can highly recommend getting a copy of

If you are writing in US English, I can highly recommend getting a copy of  Creating a

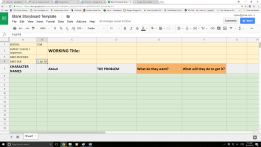

Creating a  Write the basic story. Take your characters all the way from the beginning through the middle and see that they make it to the end. If you have completed the story and have it written from beginning to end, you can concentrate on the next level of the construction phase: adding depth.

Write the basic story. Take your characters all the way from the beginning through the middle and see that they make it to the end. If you have completed the story and have it written from beginning to end, you can concentrate on the next level of the construction phase: adding depth. Sturm und Drang, as a literary form, evolved during the time of the American Revolutionary War. This was an era of global unrest and great hardship, especially in Europe. The main feature of Sturm und Drang is the expression of high emotions, strong reactions to events, and rebellion against rationalism. It is characterized by intense individualism and complex reactions.

Sturm und Drang, as a literary form, evolved during the time of the American Revolutionary War. This was an era of global unrest and great hardship, especially in Europe. The main feature of Sturm und Drang is the expression of high emotions, strong reactions to events, and rebellion against rationalism. It is characterized by intense individualism and complex reactions. So, this brings me to the subgenre of cyberpunk. One of the earliest science fiction short stories to feature a dystopian society was

So, this brings me to the subgenre of cyberpunk. One of the earliest science fiction short stories to feature a dystopian society was  Many authors whose works appeared in the early days of cyberpunk were indies hoping to go mainstream. Their short stories appeared in popular sci-fi magazines because visionary editors risked their jobs and reputations by accepting and publishing work that their readers could have rejected.

Many authors whose works appeared in the early days of cyberpunk were indies hoping to go mainstream. Their short stories appeared in popular sci-fi magazines because visionary editors risked their jobs and reputations by accepting and publishing work that their readers could have rejected.

Tad Williams’s

Tad Williams’s No matter where we live, San Francisco, Seattle, or Middle Earth, these fundamental human experiences are personal to every reader. We have each experienced pain and loss, joy and love.

No matter where we live, San Francisco, Seattle, or Middle Earth, these fundamental human experiences are personal to every reader. We have each experienced pain and loss, joy and love. Plot, in my opinion, is driven by the highs and lows. You don’t need to pay for books you won’t like. Go to the library or to the secondhand bookstore and see what they have from the NYT bestseller list that you would be willing to examine.

Plot, in my opinion, is driven by the highs and lows. You don’t need to pay for books you won’t like. Go to the library or to the secondhand bookstore and see what they have from the NYT bestseller list that you would be willing to examine. The human body moves in many ways when fighting, some of which are effective, and others not so much. In the 1990s, I studied

The human body moves in many ways when fighting, some of which are effective, and others not so much. In the 1990s, I studied

Scenes that involve violence are difficult to write well unless you know how the action will affect your protagonist. Also, you must remember to give the protagonist and the reader a small break between incidents for regrouping.

Scenes that involve violence are difficult to write well unless you know how the action will affect your protagonist. Also, you must remember to give the protagonist and the reader a small break between incidents for regrouping. Most writers are hobbyists. This is because if one intends to be a full-time writer, one must have an income.

Most writers are hobbyists. This is because if one intends to be a full-time writer, one must have an income. Events occur, disturbing my writing schedule, but I usually forgive the perpetrators and allow them to live. At that point, I revert to writing whenever I have a free moment.

Events occur, disturbing my writing schedule, but I usually forgive the perpetrators and allow them to live. At that point, I revert to writing whenever I have a free moment. As I have said many times before, being a writer is to be supremely selfish about every aspect of life, including family time.

As I have said many times before, being a writer is to be supremely selfish about every aspect of life, including family time.