Today we’re discussing narrative time, or what we call tense. Narrative tense subtly affects a reader’s perception of characters, an undercurrent that goes unnoticed after the first few paragraphs. Narrative time shapes the reader’s view of events on a subliminal level.

In grammar, the word tense indicates information about time. Tenses are usually shown by how we use the forms of verbs. The main tenses found in most languages include the past, present, and future.

In grammar, the word tense indicates information about time. Tenses are usually shown by how we use the forms of verbs. The main tenses found in most languages include the past, present, and future.

Consider the following sentences: “I eat,” “I am eating,” “I have eaten,” and “I have been eating.”

All are in the present tense, indicated by the present-tense verb of each sentence (eat, am, and have been).

Tense relates the time of an event (when) to another time (now or then). The tense you choose indicates the event’s location in time. Imagine a scene where two women meet. They know each other well but aren’t friends.

First–person, present tense: At the fish market, I find Marie holding a fish, as if she knows what to do with it. I know she doesn’t. I ask, “Did your cook finally quit?”

First-person past tense: At the fish market, I found Marie holding a fish, as if she knew what to do with it. I knew she didn’t. I asked, “Did your cook finally quit?”

Third person omniscient (past tense): At the fish market, Vivian found Marie holding a fish, as if she knew what to do with it. She knew Marie didn’t. She asked, “Did your cook finally quit?”

The above examples detail the same scene but are set in different narrative times and narrative POVs. Each change of narrative time or POV alters the feel of the story.

If we write a sentence that says a character is hot and thirsty, we leave nothing to the reader’s imagination. However, when we change the tense, we are often inspired to rephrase a thought.

If we write a sentence that says a character is hot and thirsty, we leave nothing to the reader’s imagination. However, when we change the tense, we are often inspired to rephrase a thought.

- They were hot and thirsty. (were is a subjunctive verb – passive).

- They trudged on with dry, cracked lips, yearning for a drop of water.

- We walk toward the oasis with dry, cracked lips and parched tongues.

The way we show the perception of time for these thirsty characters is the same – the narrative is in the past tense in the first two cases and the present in the third.

Subjunctives (were, was, be, etc.) are small verbs of existence, but just like adverbs that end in “ly,” they are telling words. These words fall into our narrative in the first draft because they are signals for the rewrite.

The narrative time in which the story is set (past or present tense), verb choice, and the expansion of imagery combine to change how we see the characters and events at that moment.

However, there is more to time than the grammatical narrative tense. Calendar time can get a little sloppy when we are winging it through the first draft of a manuscript.

Readers don’t notice how time passes unless it becomes unbelievable. When the passage of time is a realistic, organic part of the scenery, readers accept it and suspend their disbelief.

We try to reveal aspects of the past that are relevant to current events as the story unfolds. You can do this in two ways:

In a chronologically linear plot, you can have the backstory revealed in conversations or letters, etc., and many authors succeed at this plotting style. A calendar is helpful for this.

Other authors manipulate time. They may start with a chapter of action and commentary set in the past. The experiences shown in the prologue show the reason for present day events and actions that are yet to unfold.

Other authors manipulate time. They may start with a chapter of action and commentary set in the past. The experiences shown in the prologue show the reason for present day events and actions that are yet to unfold.

Sometimes, past events require several chapters to show the root of the current-day problem and how things didn’t go well, a “Part One.” “Part Two” begins a new section set in the present time, with the characters shaped by those past events.

If you use that kind of opening, the relevance of those events must be made clear to the reader early on in the current time section. In one forthcoming novel, I’ve employed a three-part division of the book. Part one is set twenty-five years back in time and details the actions that broke my protagonist, a battle mage. It shows why even the thought of using certain elements (magic) as weapons brings on panic attacks. Overcoming his PTSD is crucial to advancing the story.

Other authors will employ mental flashbacks, moments of characters dwelling on past events. These scenes work if they are written as the events unfolded, detailing the moments as the character lived them. The past illuminates the present.

But only if we don’t dump the information in large chunks of exposition.

I’ve read some excellent narratives where the author uses the flashback to ratchet up the suspense in a danger scene. An example could be a character trapped in a small space while a killer searches for her. She remembers being a small child during the war and being hidden in a cupboard by her father when enemy soldiers arrived. Through the keyhole, she witnesses the slaughter of her family.

I’ve read some excellent narratives where the author uses the flashback to ratchet up the suspense in a danger scene. An example could be a character trapped in a small space while a killer searches for her. She remembers being a small child during the war and being hidden in a cupboard by her father when enemy soldiers arrived. Through the keyhole, she witnesses the slaughter of her family.

A flashback scene like that serves three purposes:

- It reveals our hero’s severe claustrophobia to the reader and shows her as being human and having an Achilles Heel.

- It ratchets up the tension. The unbidden memories and the hero’s visceral response heighten her panic.

- It makes the tension feel intimate to the reader, as if they own those emotions.

Flashforwards move us in time, skipping over mundane travel and periods where the story would stagnate. A new chapter and a jump forward in time keep the story in motion—but only if it is clear that some time has passed, during which nothing out of the ordinary happened. These jumps require attention to how the transitions are handled. Mushy shifts between scenes will ruin the pacing of a story.

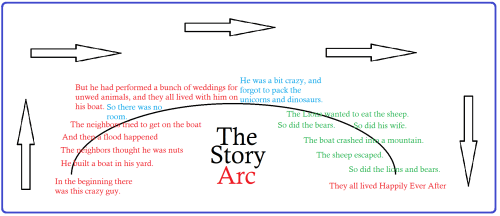

A calendar is crucial when you are manipulating time in your plot arc. Pacing becomes tricky when a plot calls for unusual timelines.

I enjoyed reading the Time Traveler’s Wife. The plot revolves around Henry’s genetic disorder, which causes him to time travel randomly and with no control, and Clare, his artist wife. She must understand the paradox and cope with his frequent absences.

It is written with alternating first-person POV. I feel the plot couldn’t advance as well if a different narrative mode had been used.

Narrative time and calendar time are separate entities. Point of view and narrative time work together.

Narrative time and calendar time are separate entities. Point of view and narrative time work together.

- Calendar time is world-building. It sets the story in a particular era and shows the passage of time.

- POV and narrative time shape the atmosphere and the ambiance of a scene.

We often “think aloud” in writing the first draft. We insert many passive phrasings into the raw narrative, words that I think of as traffic signals for future revisions. These words are a shorthand that helped us get the story down when we were writing the raw story, a guide that now shows us how we intend the narrative to go.

When you choose your grammatical tense, you have chosen a narrative time, a part of world-building that encompasses the past as well as the present and looks toward the future. It shapes the mood and atmosphere in subtle but recognizable ways.

Calendar time is the physical passage of our protagonists through the days and seasons of their stories.

Some stories work best with a first-person point of view, while others are too large and require an omniscient narrator.

Some stories work best with a first-person point of view, while others are too large and require an omniscient narrator. Head-hopping occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. It sometimes happens when using a third-person omniscient narrative because each character’s thoughts are open to the author.

Head-hopping occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. It sometimes happens when using a third-person omniscient narrative because each character’s thoughts are open to the author.

One example of a bestseller written in second person POV is

One example of a bestseller written in second person POV is  Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos. When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides.

When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides. We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often.

We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often. However, I can always write a blog post—which is how I keep my writing muscles in “fighting form.”

However, I can always write a blog post—which is how I keep my writing muscles in “fighting form.” I’m always learning. While I love to talk about writing craft, I am a far better editor than a writer. Free-lance editing is like being a hired gardener—with a bit of work, a trim here, pulling a few weeds there, you enable an author’s creative vision to become real.

I’m always learning. While I love to talk about writing craft, I am a far better editor than a writer. Free-lance editing is like being a hired gardener—with a bit of work, a trim here, pulling a few weeds there, you enable an author’s creative vision to become real.

In real life, nothing is certain. Adversity in life forges strength and understanding of other people’s challenges. Having the opportunity to make daily notes in a journal, to write poetry, blog posts, short stories, or novels is a luxury—one I am grateful for.

In real life, nothing is certain. Adversity in life forges strength and understanding of other people’s challenges. Having the opportunity to make daily notes in a journal, to write poetry, blog posts, short stories, or novels is a luxury—one I am grateful for. However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.

However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.

What motivated the action?

What motivated the action?

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages.

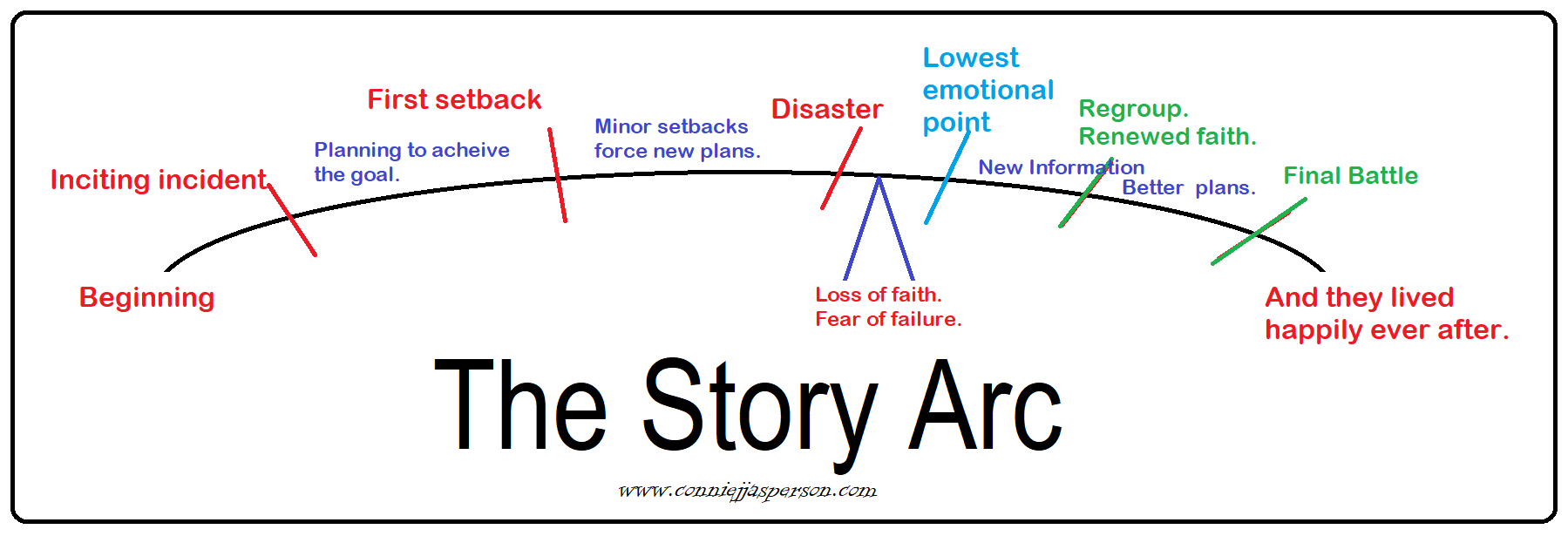

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages. This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

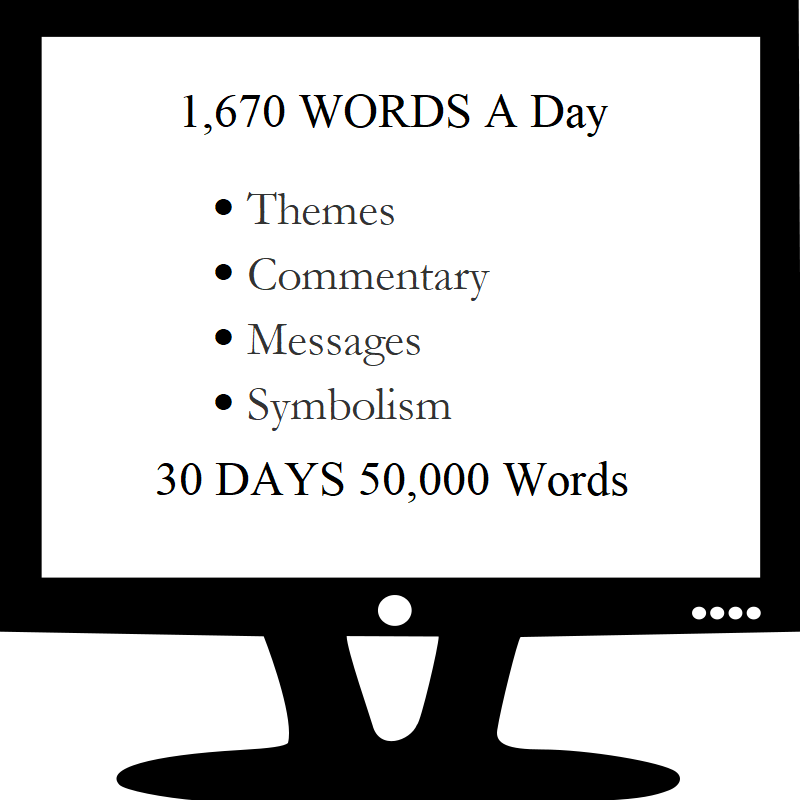

First of all, camp is relaxed, not an ordeal. You are only tied to the loose goals you set for yourself. You can choose any kind of project, whatever word count goal you feel comfortable with, and there is no pressure.

First of all, camp is relaxed, not an ordeal. You are only tied to the loose goals you set for yourself. You can choose any kind of project, whatever word count goal you feel comfortable with, and there is no pressure.

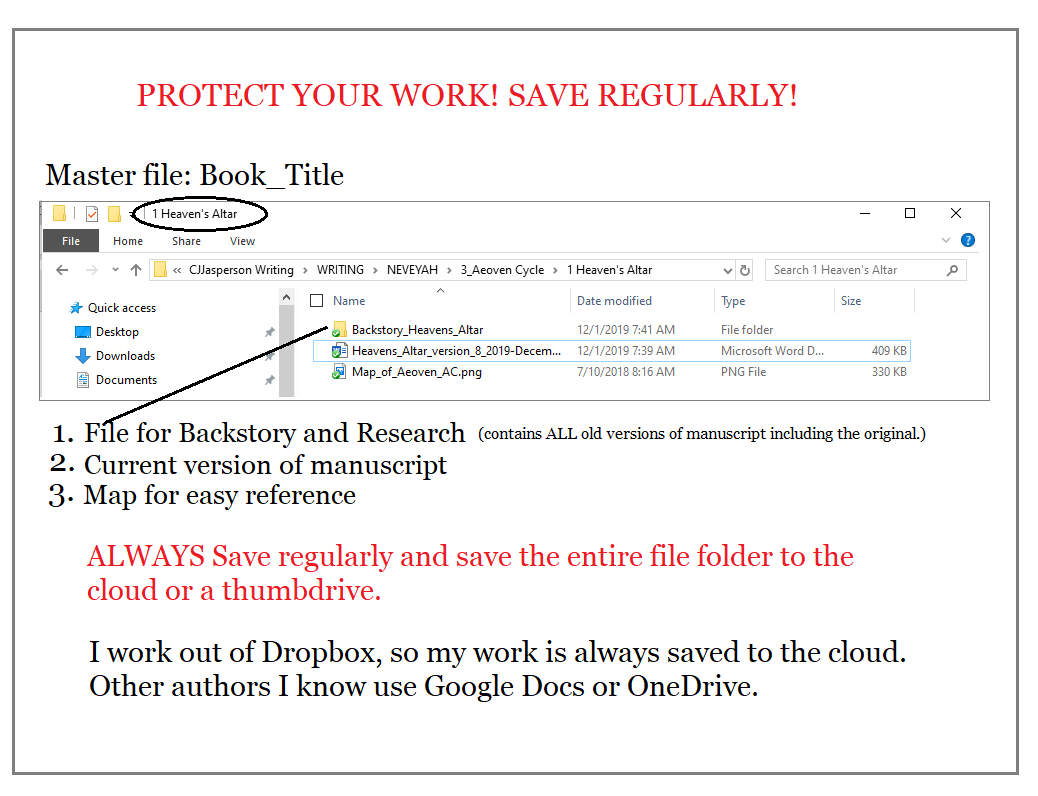

Even if you don’t have a title, name your manuscript with a good, descriptive working title, such as The_Vampire_Story. You can call it something else later.

Even if you don’t have a title, name your manuscript with a good, descriptive working title, such as The_Vampire_Story. You can call it something else later.

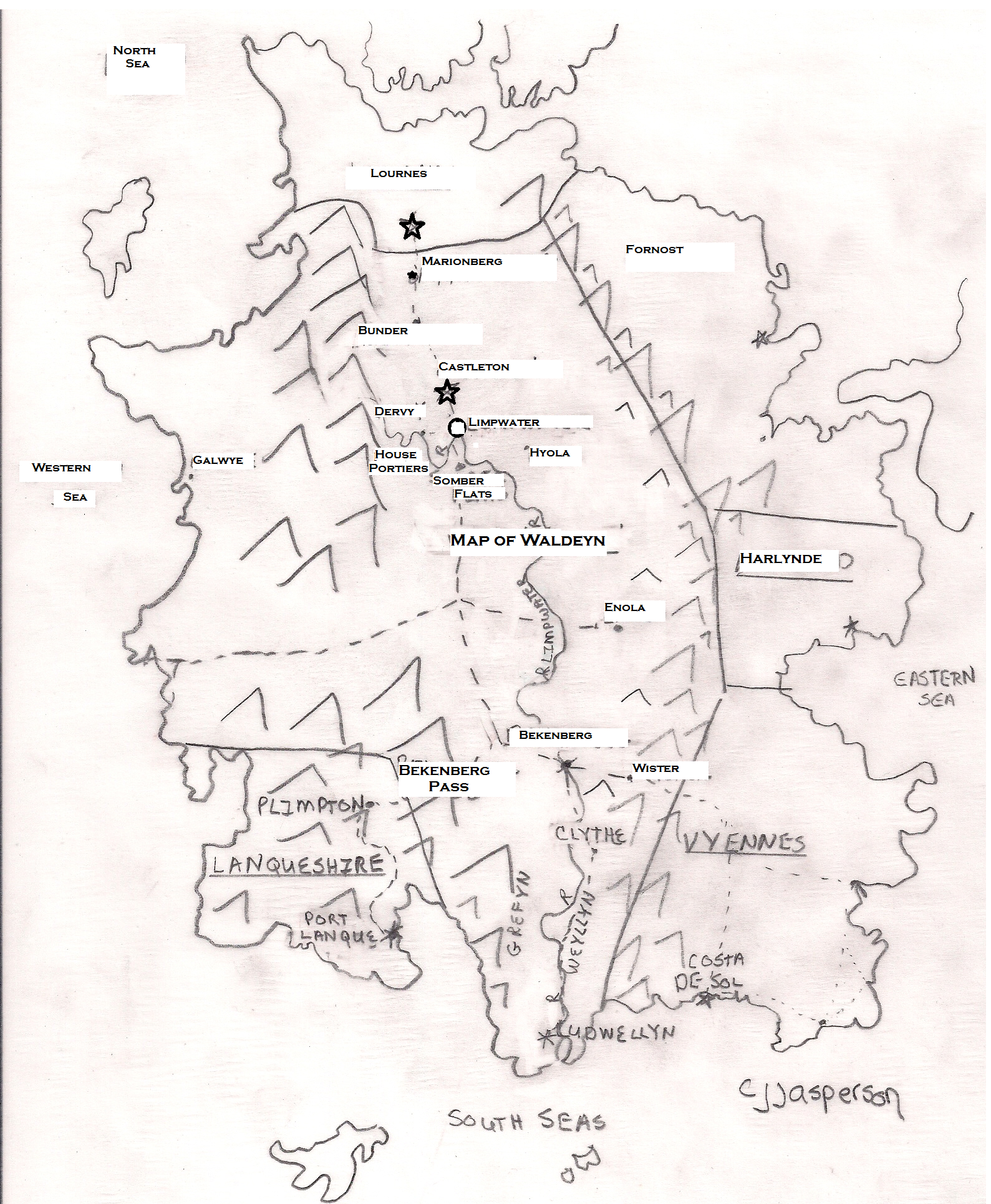

But that first book was a nightmare to edit and straighten out. It became three books, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland.

But that first book was a nightmare to edit and straighten out. It became three books, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland. Unfortunately, maps have fallen out of favor thanks to satellite technology and the GPS in our cell phones. Many people don’t know how to read a map.

Unfortunately, maps have fallen out of favor thanks to satellite technology and the GPS in our cell phones. Many people don’t know how to read a map.

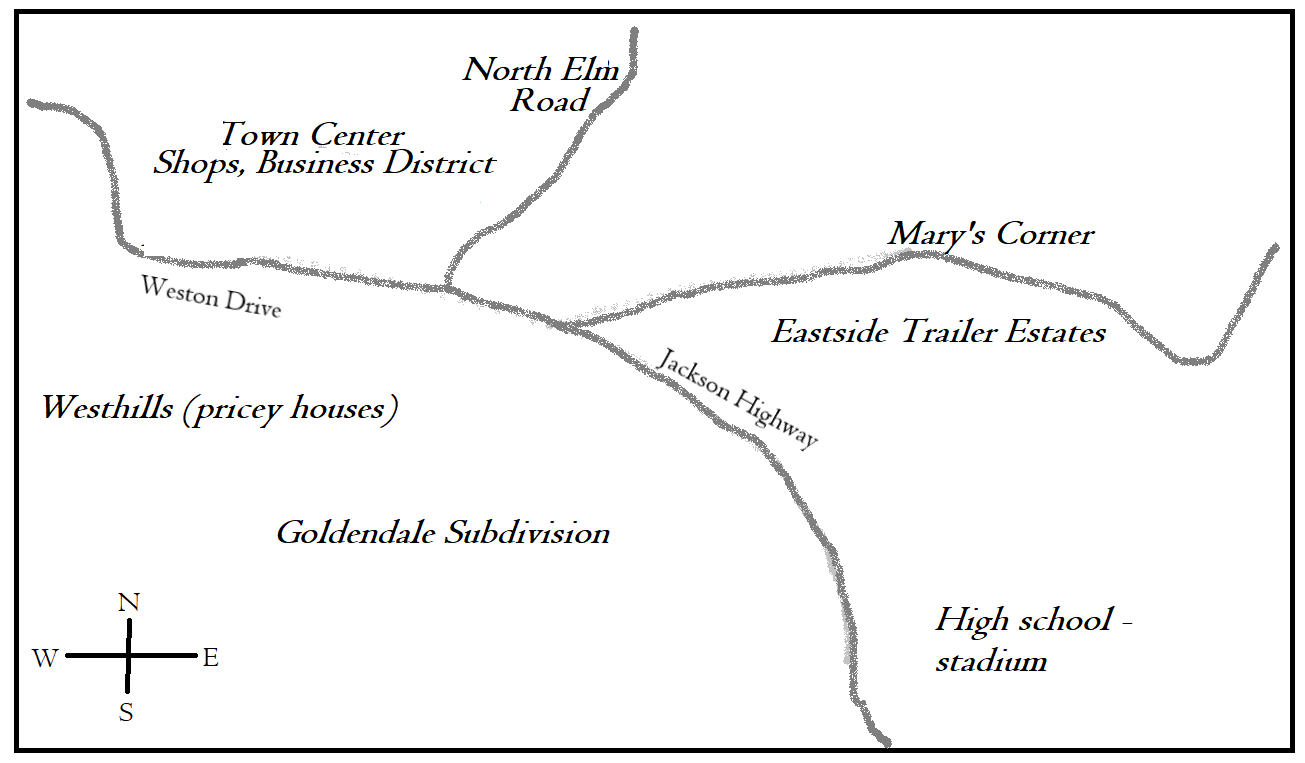

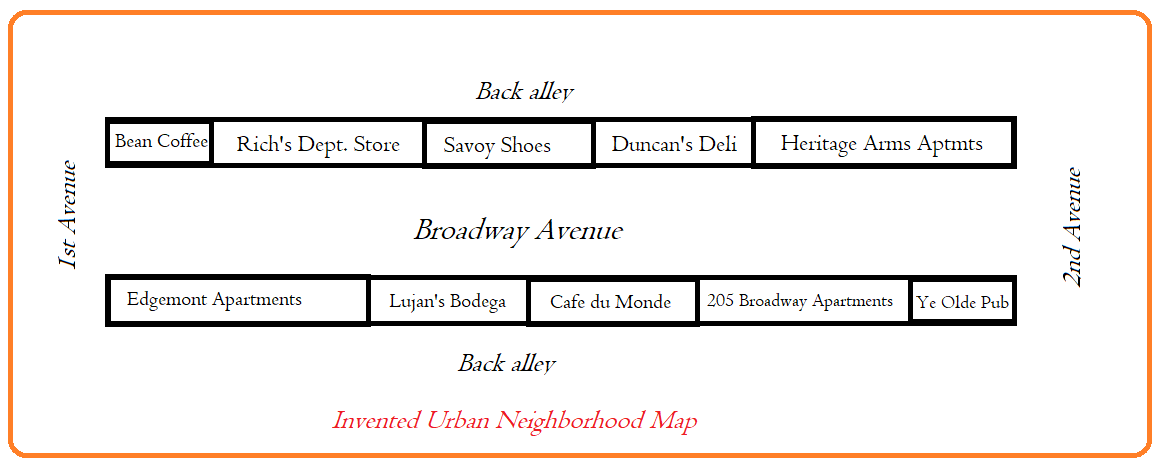

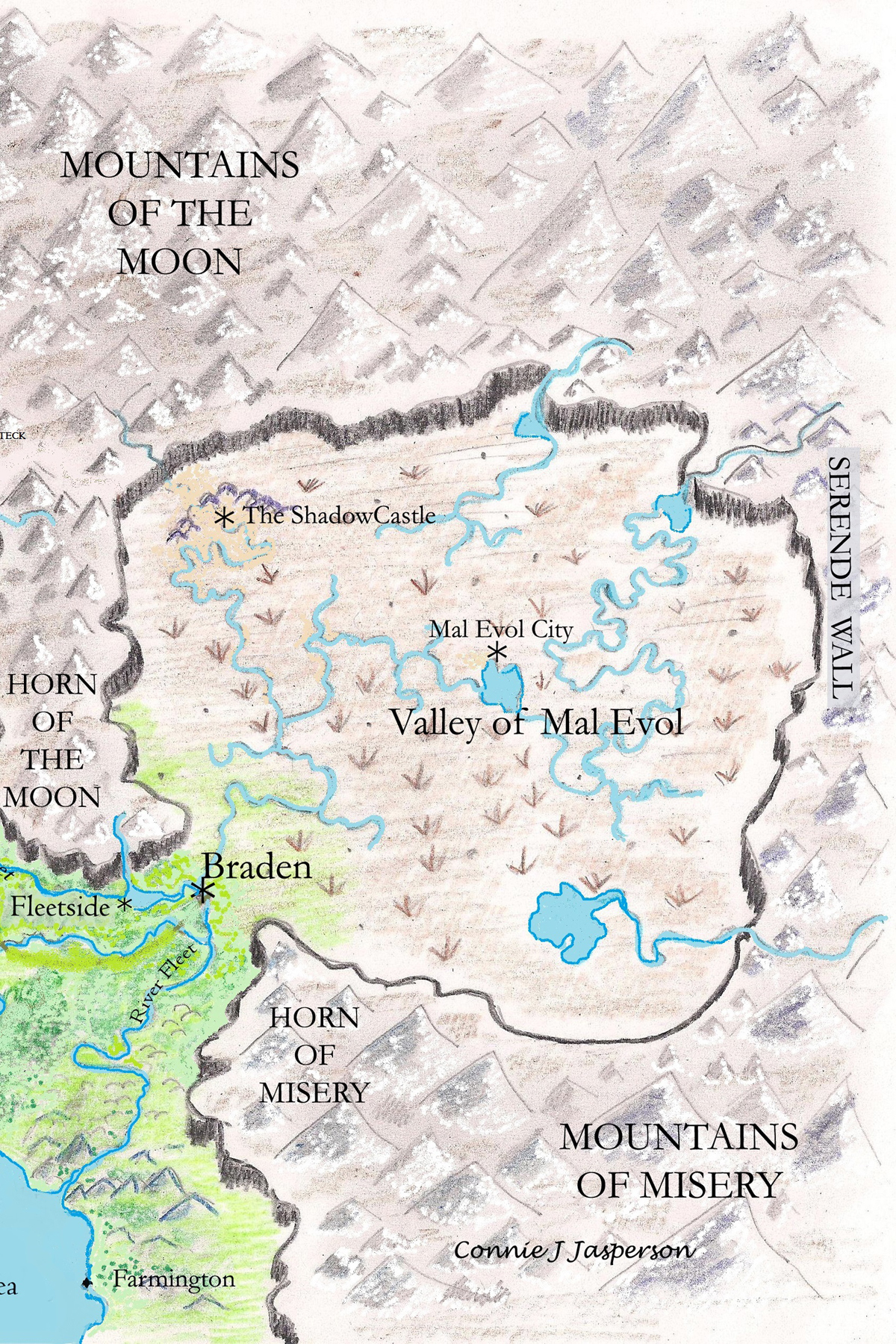

If you are designing a fantasy world, you only need a pencil-drawn map. Place north at the top, east to the right, south to the bottom, and west to the left. Those are called

If you are designing a fantasy world, you only need a pencil-drawn map. Place north at the top, east to the right, south to the bottom, and west to the left. Those are called  Use a pencil, so you can easily note whatever changes during revisions. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Lay it out like a standard map with north at the top, east on the right, south at the bottom, and west on the left.

Use a pencil, so you can easily note whatever changes during revisions. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy. Lay it out like a standard map with north at the top, east on the right, south at the bottom, and west on the left. Many towns are situated on rivers. Water rarely flows uphill. While it may do so if pushed by the force of wave action or siphoning, water is a slave to gravity and chooses to flow downhill. When making your map, locate rivers between mountains and hills.

Many towns are situated on rivers. Water rarely flows uphill. While it may do so if pushed by the force of wave action or siphoning, water is a slave to gravity and chooses to flow downhill. When making your map, locate rivers between mountains and hills. Maybe you aren’t artistic but will want a nice map later. In that case, a little scribbled map will enable a map artist to provide you with a beautiful and accurate product. An artist can give you a map containing the information readers need to enjoy your book.

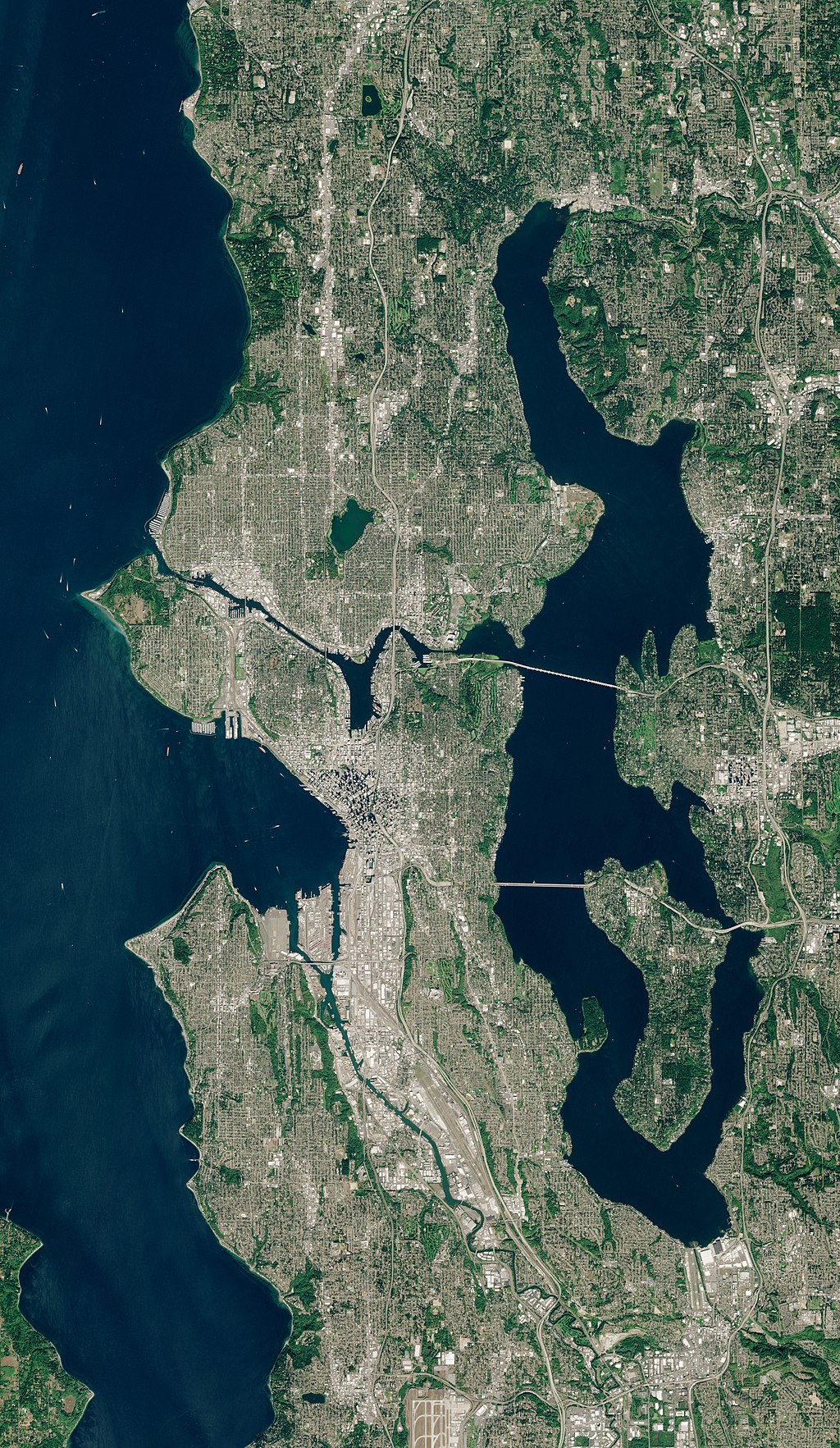

Maybe you aren’t artistic but will want a nice map later. In that case, a little scribbled map will enable a map artist to provide you with a beautiful and accurate product. An artist can give you a map containing the information readers need to enjoy your book. In my part of the world, the native forest trees I see in the world around me are mostly Douglas firs, western red cedars, hemlocks, big-leaf maples, alders, cottonwood, and ash. Because I am familiar with them, these are the trees I visualize when I set a story in a forest.

In my part of the world, the native forest trees I see in the world around me are mostly Douglas firs, western red cedars, hemlocks, big-leaf maples, alders, cottonwood, and ash. Because I am familiar with them, these are the trees I visualize when I set a story in a forest.

Every fantasy world has a setting, and that environment has a climate. Certain climates limit the variety of foods available.

Every fantasy world has a setting, and that environment has a climate. Certain climates limit the variety of foods available.

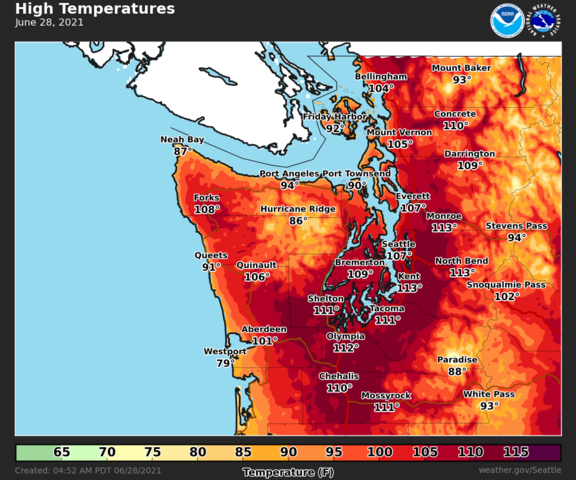

We know from bitter experience that weather affects the food we produce and influences what is available in grocery stores. Abnormal heat waves across temperate states, category 4 hurricanes along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico, and category 4 tornadoes down the center of the US and Canada, and even deep freezes in Texas and the deep south have been our lot in the last five years.

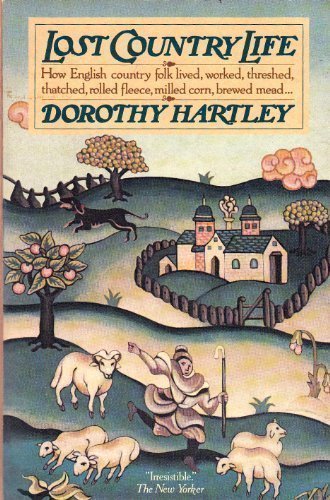

We know from bitter experience that weather affects the food we produce and influences what is available in grocery stores. Abnormal heat waves across temperate states, category 4 hurricanes along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico, and category 4 tornadoes down the center of the US and Canada, and even deep freezes in Texas and the deep south have been our lot in the last five years. Once you have decided your historical era, terrain, and overall climate, research similar areas of the real world to see how weather affects their approach to agriculture and animal husbandry. Look into the past to discover ancient agricultural methods to see how low-tech cultures fed their large populations:

Once you have decided your historical era, terrain, and overall climate, research similar areas of the real world to see how weather affects their approach to agriculture and animal husbandry. Look into the past to discover ancient agricultural methods to see how low-tech cultures fed their large populations: Also, if your story is set in a particular era, how plentiful was food at that time? Famines occurring all across Europe and Asia over the last two-thousand years are well documented. Egyptian, Incan, and Mayan history is also fairly well documented so do the research.

Also, if your story is set in a particular era, how plentiful was food at that time? Famines occurring all across Europe and Asia over the last two-thousand years are well documented. Egyptian, Incan, and Mayan history is also fairly well documented so do the research. We have witnessed monumental changes since the turn of the millennium. We know California teeters on the edge of disaster, that a water shortage threatens the lives of millions, as well as one of the largest agriculture industries in the US.

We have witnessed monumental changes since the turn of the millennium. We know California teeters on the edge of disaster, that a water shortage threatens the lives of millions, as well as one of the largest agriculture industries in the US. Tad Williams’s

Tad Williams’s When the story opens with the first novel,

When the story opens with the first novel,  By the end of the third book,

By the end of the third book,  Fate vs. free will

Fate vs. free will