My teacup has a fundamental problem. I no sooner fill it up than it is empty. I feel this is a prime example of particle physics in action. I set the cup filled with hot tea on my desk, write a few words, and it is empty when I reach for it a short while later.

It’s a mystery. The cup is full, and then it is empty, a Schrodinger’s cup of tea, there and not there.

It’s a mystery. The cup is full, and then it is empty, a Schrodinger’s cup of tea, there and not there.

But I digress.

A few years ago, I reconnected with an old word, one regaining popularity in the English language: schadenfreude (shah-den-froid-deh). This word from our Germanic roots describes the experience of happiness or self-satisfaction that comes from witnessing or hearing about another person’s troubles, failures, or humiliation.

It’s a feeling we are all familiar with, as we often experience it on a personal level.

When the rude neighbor steps in the pile of dog doo her puppy left on the sidewalk (and which she chose not to clean up), we feel a little schadenfreude.

Schadenfreude is a complex emotion. Rather than feeling sympathy towards someone’s misfortune, we find a guilty pleasure in it. Writing a little hint of schadenfreude into our narrative makes our characters feel more natural.

Decent people don’t promote bullying or harassment as a positive thing. But in the written narrative, we do want to inspire that feeling of “payback” in the reader whenever a little instant karma temporarily halts the antagonist. It’s an uncharitable emotion, but it is natural.

Humans are amused by things and incidents that violate the accepted way things should work and which do so in a non-threatening manner. We see the characters having difficulty in certain situations and find humor in the fact their dilemmas are so relatable.

Humans are amused by things and incidents that violate the accepted way things should work and which do so in a non-threatening manner. We see the characters having difficulty in certain situations and find humor in the fact their dilemmas are so relatable.

When an author injects a little self-mocking humor into a narrative, the reader feels an extra burst of endorphins and keeps turning the pages. The way the characters react to these situations is what keeps me reading.

I love exchanges of snarky dialogue, mocking irreverence, and sarcasm. They liven up regrouping scenes and add interest to moments of transition from one scene to the next.

I am keenly aware that what appeals to me might not to you.

The truth is, humor is as much cultural as it is personal. The things we find hilarious vary widely from person to person. Sometimes the strangest things will crack me up, things another person sees no humor in.

Some people have an earthy sense of humor, while others are more cerebral. For me, the best comedy occurs when the conventional rules are undercut or warped by a glaring incongruity, something out of place, contrasted against the ordinary.

I have never liked slapstick as a visual comedy because I see it as a form of bullying, and I just can’t watch it. But in the narrative, putting your characters through a little ironic disaster now and then keeps a dark theme moving forward.

Gallows humor is more than merely mocking ill fortune. The tendency to find humor in a desperate or hopeless situation is a fundamental human emotion. When I was growing up, my family ran on “gallows humor” and still does, to a certain extent. We put the “fun” in dysfunctional.

This is why gallows humor finds its way into my work. We all need something to lighten up with now and then.

Humor in the narrative adds both depth and pathos to the characters. It humanizes them, and you don’t need to resort to an info dump to show their personality. Each character’s sense of humor (or lack thereof) demonstrates who they are and why we should care about them.

I can’t know what you find humorous, but I do know what makes me smile. I like snark and witty comments, a bit of banter back and forth in the face of impending trouble.

I like things that surprise me, situations that detour sharply from the expectations of normal. In Bleakbourne on Heath, I took this to an extreme with the characters of the two knights, Lancelyn and Galahad. I gave Lance a real problem – all magic rebounds from him. Only one person can remove that spell, Morgause, because she cursed him with it.

I like things that surprise me, situations that detour sharply from the expectations of normal. In Bleakbourne on Heath, I took this to an extreme with the characters of the two knights, Lancelyn and Galahad. I gave Lance a real problem – all magic rebounds from him. Only one person can remove that spell, Morgause, because she cursed him with it.

In a world of sorcerers and magic, that is a curse offering many opportunities for trouble. (Heh heh!)

I like putting my protagonists in situations where they must deal with embarrassment, do a dirty job, and learn they are merely human after all.

It adds a little fresh air at places where the character arcs could stagnate.

The act of writing humor occurs on an organic level, frequently arising during the first draft before the critical mind has a chance to iron it out. It falls out of my mind with the bare bones of the narrative.

I do have a cruel streak when it comes to my written characters. The ability to laugh at oneself and to learn from missteps is critical in real life. Admitting you are the architect of your own disaster and accepting your own human frailty is a major step to adulthood.

I do have a cruel streak when it comes to my written characters. The ability to laugh at oneself and to learn from missteps is critical in real life. Admitting you are the architect of your own disaster and accepting your own human frailty is a major step to adulthood.

So, now that I have finished that rant, I shall refill my Schrodinger’s-brand teacup and relax on the balcony, daydreaming and watching the street below. Perhaps this time, I won’t lapse into a fugue state as I drink it.

Do you write your heroes with few flaws, or do you portray them as “warts and all?” That becomes a matter of what you want to read.

Do you write your heroes with few flaws, or do you portray them as “warts and all?” That becomes a matter of what you want to read. Still, I write stories about people who might have existed and have their own views of morality. In each tale, I try to get into the characters’ heads. I want to understand why they sometimes make terrible choices, acts that profoundly change their lives.

Still, I write stories about people who might have existed and have their own views of morality. In each tale, I try to get into the characters’ heads. I want to understand why they sometimes make terrible choices, acts that profoundly change their lives. To me, the flawed hero has much to offer us. In my most recently published book, a stand-alone novel called

To me, the flawed hero has much to offer us. In my most recently published book, a stand-alone novel called

The difference between the antagonist and the hero is the amount of grayness in their moral compass. When does the gray area of morality begin edging toward genuinely dark? What are they not willing to do to achieve their goal?

The difference between the antagonist and the hero is the amount of grayness in their moral compass. When does the gray area of morality begin edging toward genuinely dark? What are they not willing to do to achieve their goal? One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year.

One of my favorite authors writes great storylines and creates wonderful characters. Unfortunately, the quality of his work has deteriorated over the last decade. It’s clear that he has succumbed to the pressure from his publisher, as he is putting out four or more books a year. This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions.

This frequently happens to me in a first draft, but whoever is editing for him is letting it slide, as it pads the word count, making his books novel-length. I suspect they don’t have time to do any significant revisions. When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t.

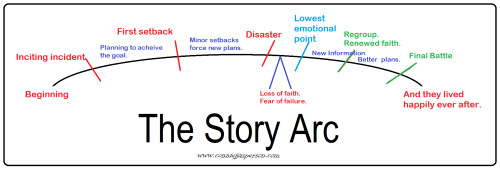

When we lay down the first draft, the story emerges from our imagination and falls onto the paper (or keyboard). Even with an outline, the story forms in our heads as we write it. While we think it is perfect as is, it probably isn’t. Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first.

Inadvertent repetition causes the story arc to dip. It takes us backward rather than forward. In my work, I have discovered that the second version of that idea is usually better than the first. Here are a few things that stand out when I do this:

Here are a few things that stand out when I do this: If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be.

If you have the resource of a good writing group, you are a bit ahead of the game. I suggest you run each revised chapter by your group and listen to what they say. Some of what you hear won’t be useful, but much will be. I am fortunate to have excellent friends willing to do this for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on.

I am fortunate to have excellent friends willing to do this for me. Their suggestions are thoughtful and spot-on. In my work, the suggestions offered by the beta reader (first reader) guide and speed up the revision process. My editor can focus on doing her job without being distracted by significant issues that should have been caught early on.

In my work, the suggestions offered by the beta reader (first reader) guide and speed up the revision process. My editor can focus on doing her job without being distracted by significant issues that should have been caught early on. Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable?

Characters: Is the point of view character (protagonist) clear? Did you understand what they were feeling? Were they likable? Did you identify with and care about them? Were there various character types, or did they all seem the same? Were their emotions and motivations clear and relatable? Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript.

Editing is a process unto itself and is the final stage of making revisions. The editor goes over the manuscript line-by-line, pointing out areas that need attention: awkward phrasings, grammatical errors, missing quotation marks—many things that make the manuscript unreadable. Sometimes, major structural issues will need to be addressed. Straightening out all the kinks may take more than one trip through a manuscript. An editor is not the author. They can only suggest remedies, but ultimately all changes must be approved and implemented by the author.

An editor is not the author. They can only suggest remedies, but ultimately all changes must be approved and implemented by the author. A reader won’t be familiar with it and will notice what we have overlooked.

A reader won’t be familiar with it and will notice what we have overlooked. When observed by others, a person who is daydreaming appears lazy. Mind-wandering has no obvious purpose, but it is critical for creativity. Every groundbreaking discovery in science, every great invention we enjoy today—all were inspired by ideas that came to a person while thinking about something else or when they were mind-wandering.

When observed by others, a person who is daydreaming appears lazy. Mind-wandering has no obvious purpose, but it is critical for creativity. Every groundbreaking discovery in science, every great invention we enjoy today—all were inspired by ideas that came to a person while thinking about something else or when they were mind-wandering. My oldest daughter, looking at our dinner, a casserole of beans with cornbread baked on top like a cobbler: “What the heck is that?”

My oldest daughter, looking at our dinner, a casserole of beans with cornbread baked on top like a cobbler: “What the heck is that?” Perception is in the eye of the beholder. Observation and thought are seeds that inspire extrapolation, leading the viewer to come away with new ideas. When I see the story captured in a single scene by an artist, my mind always surmises more than the painting shows. I see the picture as depicting the middle of the story and imagine what came before and what happened next. Unintentionally, I put a personal spin on my interpretation, and ideas are born. I don’t mean to, but everyone does.

Perception is in the eye of the beholder. Observation and thought are seeds that inspire extrapolation, leading the viewer to come away with new ideas. When I see the story captured in a single scene by an artist, my mind always surmises more than the painting shows. I see the picture as depicting the middle of the story and imagine what came before and what happened next. Unintentionally, I put a personal spin on my interpretation, and ideas are born. I don’t mean to, but everyone does. This means that daydreaming is actually good for you. It boosts the brain, making our thought process more effective. Letting the mind wander allows a kind of ‘default neural network’ to engage when our brain is at wakeful rest, as in meditation, rather than actively focusing on the outside world. When we daydream, our brains can process tasks more effectively.

This means that daydreaming is actually good for you. It boosts the brain, making our thought process more effective. Letting the mind wander allows a kind of ‘default neural network’ to engage when our brain is at wakeful rest, as in meditation, rather than actively focusing on the outside world. When we daydream, our brains can process tasks more effectively. You could be watching the birds, as my husband and I often do. Or maybe you’re perusing the display in a local art gallery or listening to music. I love all genres of music, but for writing I often find inspiration in powerhouse classical pieces such as Orff’s cantata,

You could be watching the birds, as my husband and I often do. Or maybe you’re perusing the display in a local art gallery or listening to music. I love all genres of music, but for writing I often find inspiration in powerhouse classical pieces such as Orff’s cantata,  Today, however, I plan a long walk along the beach.

Today, however, I plan a long walk along the beach. I have no trouble selling my friends’ books – I’ve read them all and love them, and love selling them. Maybe I can sell their books because I’m not emotionally invested in their creation, but I am invested as a reader.

I have no trouble selling my friends’ books – I’ve read them all and love them, and love selling them. Maybe I can sell their books because I’m not emotionally invested in their creation, but I am invested as a reader. Next week on this blog we will talk about the creative process and the importance of mind-wandering. We’ll also talk about why it is important to beta read for your fellow writers, and how to be a good reader, one who gives positive feedback and offers constructive suggestions.

Next week on this blog we will talk about the creative process and the importance of mind-wandering. We’ll also talk about why it is important to beta read for your fellow writers, and how to be a good reader, one who gives positive feedback and offers constructive suggestions. I have “pantsed it” occasionally, which can be liberating but for me, there always comes a point where I realize my manuscript has gone way off track and is no longer fun to write. Then I must return to the point where the story stopped working and make an outline.

I have “pantsed it” occasionally, which can be liberating but for me, there always comes a point where I realize my manuscript has gone way off track and is no longer fun to write. Then I must return to the point where the story stopped working and make an outline. The first tool is a sense of balance. Every published novel has entire sections that were cut or rewritten at least once before it got to the editing stage.

The first tool is a sense of balance. Every published novel has entire sections that were cut or rewritten at least once before it got to the editing stage. At first, the page is only a list of headings that detail the events I must write for each chapter. I know what end I have to arrive at. But the chapter headings are pulled out of the ether, accompanied by the howling of demons as I force my plot to take shape:

At first, the page is only a list of headings that detail the events I must write for each chapter. I know what end I have to arrive at. But the chapter headings are pulled out of the ether, accompanied by the howling of demons as I force my plot to take shape: Don’t be afraid to rewrite what isn’t working. Save everything you cut because I guarantee you will want to reuse some of that prose later at a place where it makes more sense.

Don’t be afraid to rewrite what isn’t working. Save everything you cut because I guarantee you will want to reuse some of that prose later at a place where it makes more sense.

Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like

Some novels are character-driven, others are event-driven, but all follow an arc. I’m a poet, and while I read in every genre, I seek out literary fantasy, novels with a character-driven plot. These are works by authors like  And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality.

And the prose … words with impact, words combined with other words, set down in such a way that I feel silly even thinking I can write such works. Thankfully, my editor weeds out pretentious hyperbole and slaps me back to reality. This part of the novel is often difficult for me to get right. The protagonist must be put through a personal crisis. Their inner world must be shaken to the foundations.

This part of the novel is often difficult for me to get right. The protagonist must be put through a personal crisis. Their inner world must be shaken to the foundations. This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew.

This emotional low point is necessary for our characters’ personal arcs. It is the place where they are forced to face their weaknesses and rebuild themselves. They must discover they are stronger than they ever knew. And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin?

And what of my female protagonist? Where does her story begin? I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page.

I must introduce a story-worthy problem in those pages, a test propelling the protagonist to the middle of the book. The opening paragraphs are vital. They are the hook, the introduction to my voice, and must offer a reason for the reader to continue past the first page. My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

My favorite books open with a minor conflict, evolving to a series of more significant problems, working up to the first pinch point, where the characters are set on the path to their destiny.

The inciting incident is followed by a series of plot points, places where complications are introduced into the narrative.

The inciting incident is followed by a series of plot points, places where complications are introduced into the narrative. The opening setting for this story is a small town in an exceedingly rural part of Thurston County. One must travel at least ten miles in any direction to find another city. After sundown, you must drive on narrow, winding, pitch-black country roads. I, the protagonist in my story, suffer from severe night blindness, which meant we had to return home before sundown, putting a real crimp in our social life.

The opening setting for this story is a small town in an exceedingly rural part of Thurston County. One must travel at least ten miles in any direction to find another city. After sundown, you must drive on narrow, winding, pitch-black country roads. I, the protagonist in my story, suffer from severe night blindness, which meant we had to return home before sundown, putting a real crimp in our social life. Major surgeries happened for the other two, and I was many miles away to the south, getting our house on the market. But our sons and daughters are entering middle age, and our older grandchildren are adults. Despite our worries, our granddaughters proved they were mature and more than capable of handling their lives.

Major surgeries happened for the other two, and I was many miles away to the south, getting our house on the market. But our sons and daughters are entering middle age, and our older grandchildren are adults. Despite our worries, our granddaughters proved they were mature and more than capable of handling their lives. The protagonists are settling into the new neighborhood. One of the niftiest things about their community is the Starbucks—and yes, I did say Starbucks. The owners of the

The protagonists are settling into the new neighborhood. One of the niftiest things about their community is the Starbucks—and yes, I did say Starbucks. The owners of the  I find that writing is easy here. Creativity comes in bursts, and I feel good about my writing. We have pared our possessions down to the point that they don’t possess us—something you don’t realize is a problem until you are faced with serious downsizing.

I find that writing is easy here. Creativity comes in bursts, and I feel good about my writing. We have pared our possessions down to the point that they don’t possess us—something you don’t realize is a problem until you are faced with serious downsizing.