We are still working on the second draft of our manuscript. We have searched for our code words and examined our character arcs for agency and consequences.

The Second Draft: Decoding My Mental Shorthand #writing

The Second Draft: agency and consequences #writing

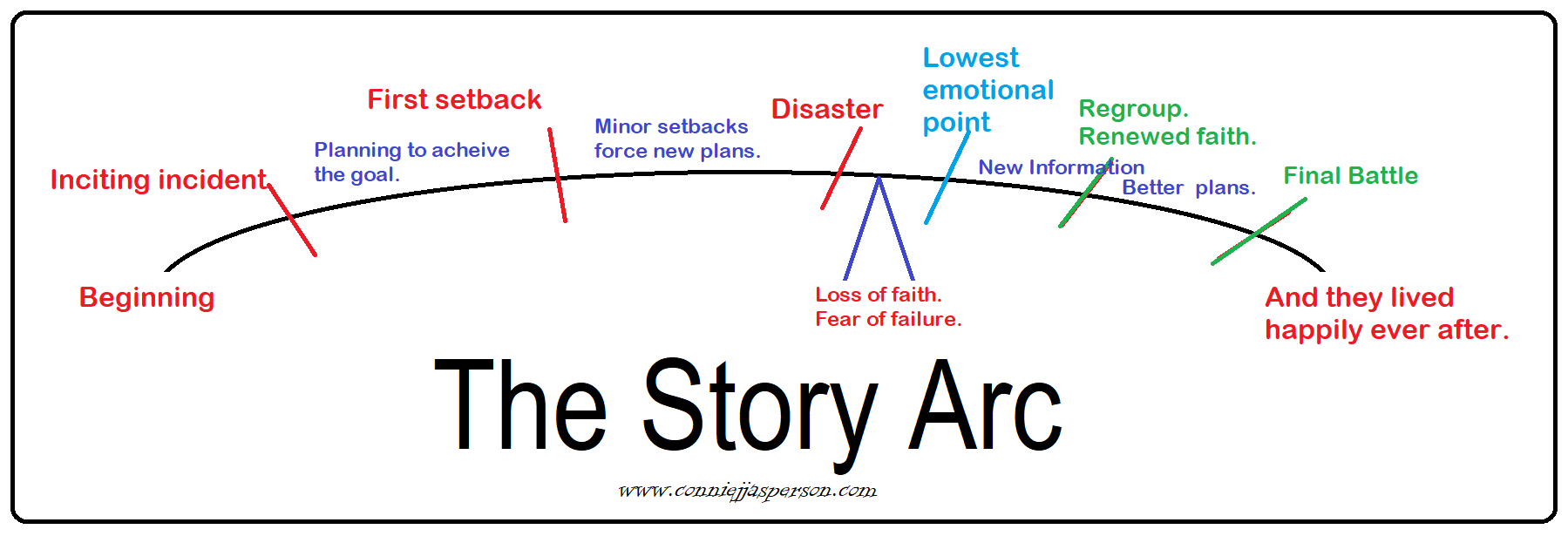

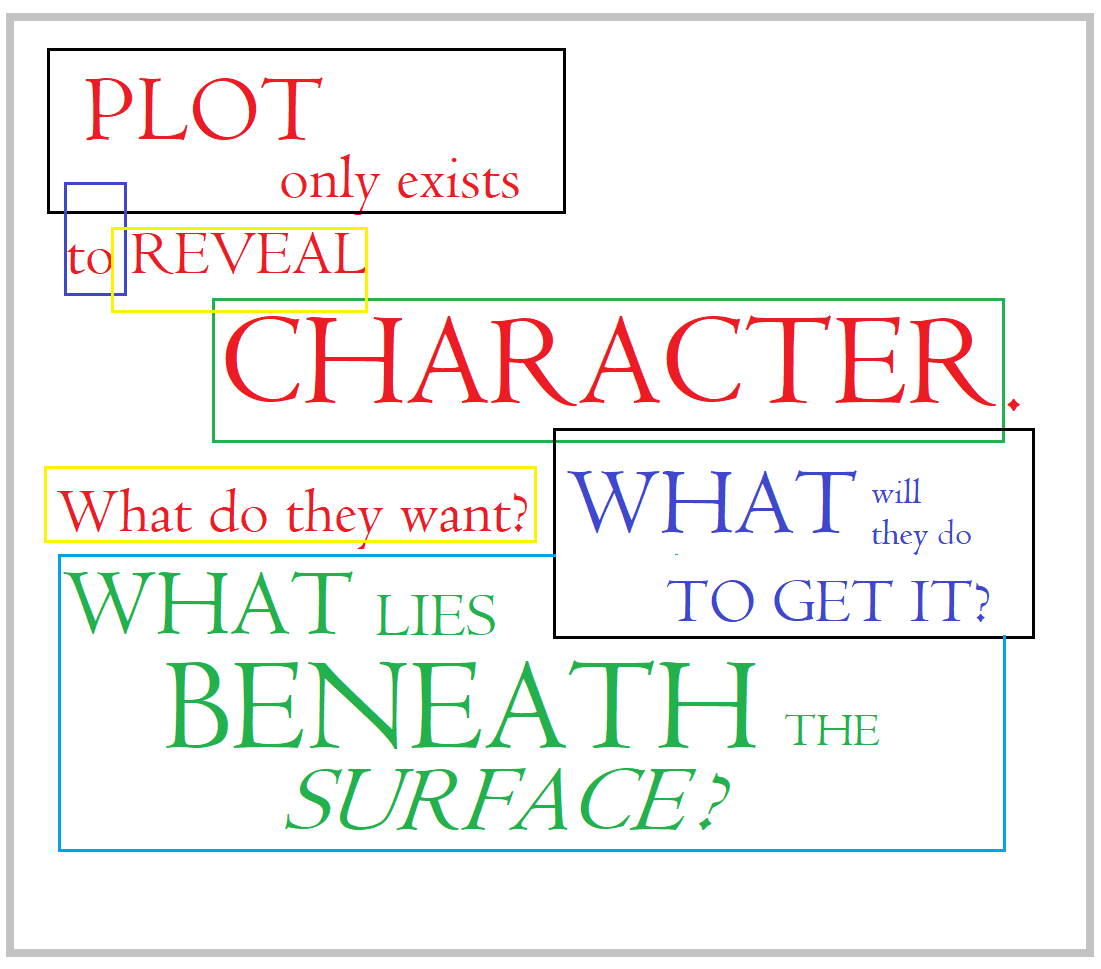

Today, we’re looking at the arc of the plot. This is a good opportunity to open a new document and answer a few questions about your story. The list of questions and their answers will inform you of the areas that need more work before you send the manuscript to a beta reader.

Today, we’re looking at the arc of the plot. This is a good opportunity to open a new document and answer a few questions about your story. The list of questions and their answers will inform you of the areas that need more work before you send the manuscript to a beta reader.

First, let’s take a second look at the overarching objective. This is the reason the story exists, and we made a stab at identifying it in the first draft. But now we want to make that problem clear.

- Is the quest worthy of a story? What does the hero need, and would they risk everything to acquire it?

- Have we shown how badly they want it and, most importantly, why they are so desperate for it?

- Why do they feel entitled to it?

- How far are they willing to go to acquire it?

Second, we examine the antagonist. Have we shown the opposition as clearly as we have the protagonist? The whole story hinges on whether or not our protagonist faces a real threat. A weak enemy is no threat at all, so

Who is the antagonist?

Who is the antagonist?- Do they have a personality that shows them as rounded and multidimensional rather than as a two-dimensional cartoon villain?

- Do they change and evolve as a person throughout the story, for good or for evil? A character arc must encompass several stages of personal growth. What those stages are is up to you and depends on the story you are telling.

- What do they want?

- Why do they feel entitled to it?

- How far are they willing to go to get it?

Third, how convincing is the inciting incident? I learned this the hard way—long lead-ins don’t hook the reader. Long lead-ins offer too much opportunity for the inclusion of insidious info dumps.

- Whether we show it in the prologue or the opening chapter, the first event, the inciting incident, changes everything and launches the story. The universe that is our story begins expanding at that moment.

- The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

- The threat and looming disaster must be made clear to the reader at the outset. Nebulous threats mean nothing in real life, although they cause a lot of subconscious stress.

- Those vague threats might be the harbinger of what is to come in a book, but they only work if the danger materializes quickly and the roadblocks to happiness soon become apparent.

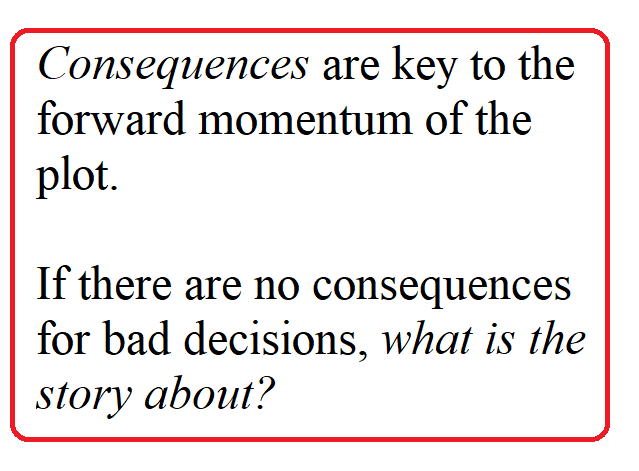

Fourth, let’s look at logic and the pinch points. Pinch points (events that threaten the quest) are the cogs that keep the wheels of your story turning. How strong are the pinch points in this story?

- Was this failure the logical outcome of the characters’ decisions? Or does this event feel random, like spaghetti tossed at a wall to see what sticks?

- Does the first pinch point feel strong enough to hook a reader?

The internet says that pinch points frequently occur between moving objects or parts of a machine.

Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism.

Consider cogs: they are engineered to interlock with each other, and when they move close enough that one cog interlocks and turns another, they move other parts of the mechanism.

When a machine is powered by mechanical or electrical means, the places where the cogs meet other cogs or other parts of the machinery are the danger zones, the places where people can be injured or even killed.

So, our narrative is our machine, and the events (pinch points) are the cogs that move it along.

Logic is the oil that keeps our gears turning.

Fifth: midpoint: What are the circumstances in which we find each character at the midpoint?

From the midpoint to the final plot point, pacing is critical, and the reader must be able to see how the positive and negative consequences affect the emotions of ALL the characters. We must show their emotional and physical condition and the circumstances in which they now find themselves.

The antagonist will be pleased, perhaps elated.

The protagonist will be worried, perhaps depressed.

- Did we fully explore how the events emotionally destroy them?

- Did we shed enough light on how their personal weaknesses are responsible for the bad outcome?

- Did we show how this failure causes the protagonist to question everything they once believed in?

- Did we offer them hope? What did we offer them that gave them the courage to persevere and face the final battle?

- Finally, did we explore how this emotional death and rebirth event makes them stronger?

Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms.

Each hiccup on the road to glory must tear the heroes down. Events and failures must break them emotionally and physically so that in the book’s final quarter, they can be rebuilt, stronger, and ready to face the enemy on equal terms.

Why does the antagonist have the upper hand? What happens at the midpoint to change everything for the worse?

Sixth: we look closely at the last act, which is the final quarter of the story.

- At the ¾ point, your protagonist and antagonist should have gathered their resources and companions.

- Each should believe they are as ready to face each other as they can be under the circumstances.

The final pages of the story are the reader’s reward for sticking with it to that point.

- Did we hold the solution just out of reach for the first ¾ of the narrative? Did we lure the reader to stay with us by giving them the promise of a solution?

- Did we show clearly that every time our characters nearly resolved their situation, they didn’t, and things got worse?

- Did we bring the protagonist and antagonist together for a face-to-face meeting?

- Was that meeting an epic conflict that deserved to be included in that story?

- Did that meeting bring the story to a solid conclusion?

- How well did we choreograph that final meeting?

Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it.

Confrontations are chaotic. It’s our job to control that chaos and create a narrative with an ending that is as intense as our imaginations and logic can make it.

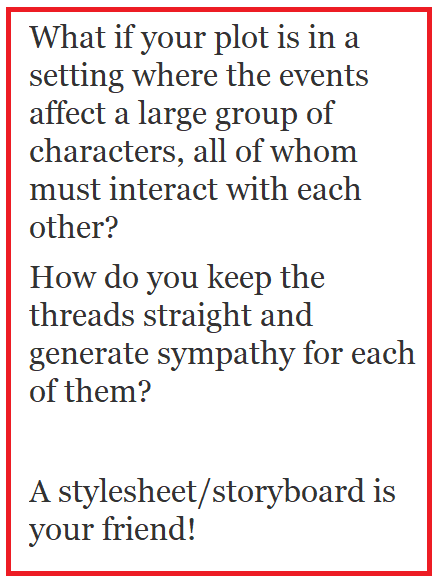

Once we have examined the plot arc and are satisfied with its outcome, we may think it’s ready for a beta reader.

But it might not be, as we still have a few steps to complete. The beta reader’s comments will inform how we approach our third draft, so we want the manuscript we give them to be as free of easily resolved bloopers and distractions as possible. That way they will be better able to see the strengths of the story as well as the weaknesses.

Next week, we’ll examine the next steps to making a manuscript ready for a trusted beta reader. I’ll also discuss how I find readers who can accept that my story still has flaws and who understand what I am asking them to look for.

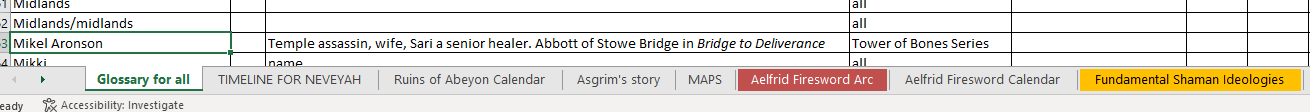

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

This happens because my characters have agency and sometimes run amok. Thus, in the second draft, I examine the freedom I give my characters to introduce their own actions and reactions within the story.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

When the writing commences, the characters make choices and say things that surprise me. They can do this because I allow them agency.

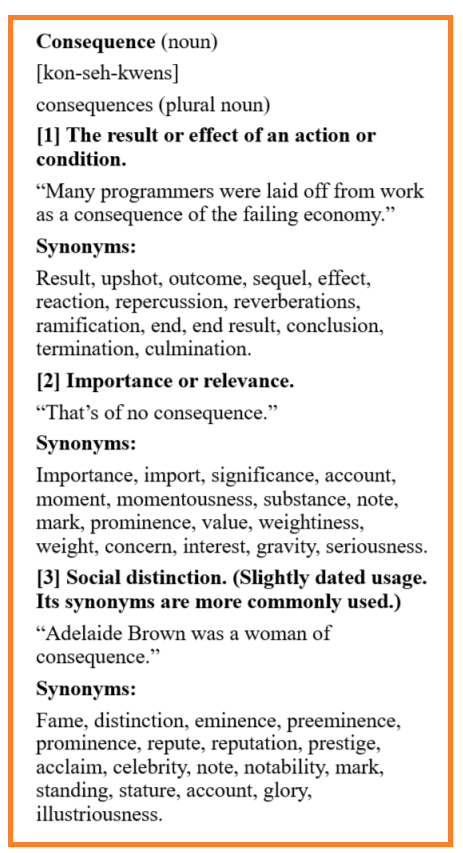

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.

Fortunately, they are rescued by Gandalf. While he is hiding, Bilbo discovers several historically important weapons. One of them is Sting, a blade that fits Bilbo perfectly as a sword. This is a positive consequence, as the blade is crucial to Bilbo’s story and later to Frodo’s story.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images.

It follows that certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. Code words are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One word, one packet of letters will serve many purposes and convey a myriad of mental images. I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.

I want to avoid that sin in my work, but what are my code words? What words are being inadvertently overused as descriptors? A good way to discover this is to make a word cloud. The words that see the most screen time will be the largest.  endured

endured Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display.

Sometimes, the only thing that works is the brief image of a smile. Nothing is more boring than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I want to know what is happening inside our characters and can be put off by an exaggerated outward display. If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is

If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is

I was divorced from hubby number three in 1997, and oddly enough, things became much easier financially. I was able to get by with only one job, even while raising my last teenager. (See? Everyone has a soap opera life, even famously unknown authors.)

I was divorced from hubby number three in 1997, and oddly enough, things became much easier financially. I was able to get by with only one job, even while raising my last teenager. (See? Everyone has a soap opera life, even famously unknown authors.)

Another arc takes the protagonist on a journey that can end several different ways, all of them taking our characters down a winding path with many choices, roads not taken. They also are altered by their experiences for good or ill.

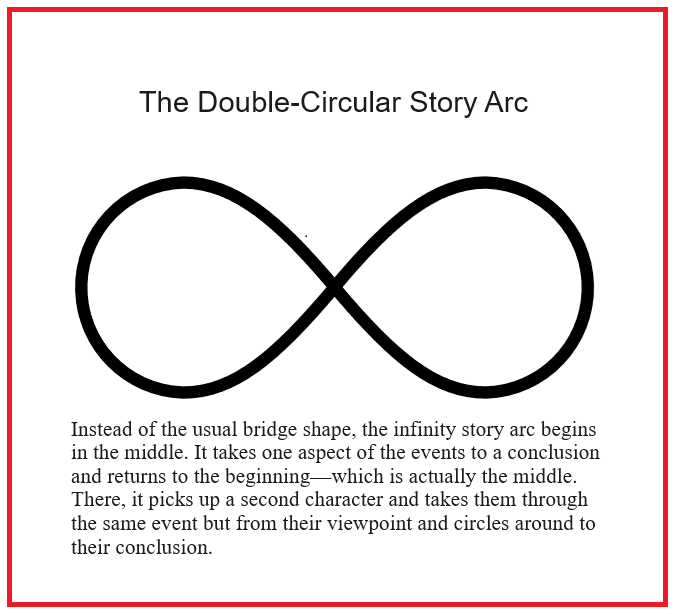

Another arc takes the protagonist on a journey that can end several different ways, all of them taking our characters down a winding path with many choices, roads not taken. They also are altered by their experiences for good or ill. Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc.

Knowing my intended word count helps me create a story, from drabbles to novels. For me, it works in stories with a traditional arc as well as those with a circular arc. In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

In a circular narrative, the story begins at point A, takes the protagonist through life-changing events, and brings them home, ending where it started. The starting and ending points are the same, and the characters return home, but they are fundamentally changed by the story’s events.

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch).

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating a believable atmosphere when limited to only a small word count. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I wanted to expand on the theme of dragons and use it to show two aspects of a place whose national symbol is the Red Dragon (Welsh: Y Ddraig Goch). Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be.

Most of my novels and short stories begin life as exchanges of dialogue between two characters. Their conversations shed light on what each character’s role in the story might be. Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

Action: She comes down for coffee. He holds a notebook, gathers pens, and stands.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning.

My writing projects begin with an idea, a flash of “What if….” Sometimes, that “what if” is inspired by an idea for a character or perhaps a setting. Maybe it was the idea for the plot that had my wheels turning. I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending.

I’m writing a fantasy, and I know what must happen next in the novel because the core of this particular story is romance with a side order of mystery. I see how this tale ends, so I am brainstorming the characters’ motivations that lead to the desired ending. Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals.

Plots are comprised of action and reaction. I must place events in their path so the plot keeps moving forward. These events will be turning points, places where the characters must re-examine their motives and goals. Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

Our characters are unreliable witnesses. The way they tell us the story will gloss over their failings. The story happens when they are forced to rise above their weaknesses and face what they fear.

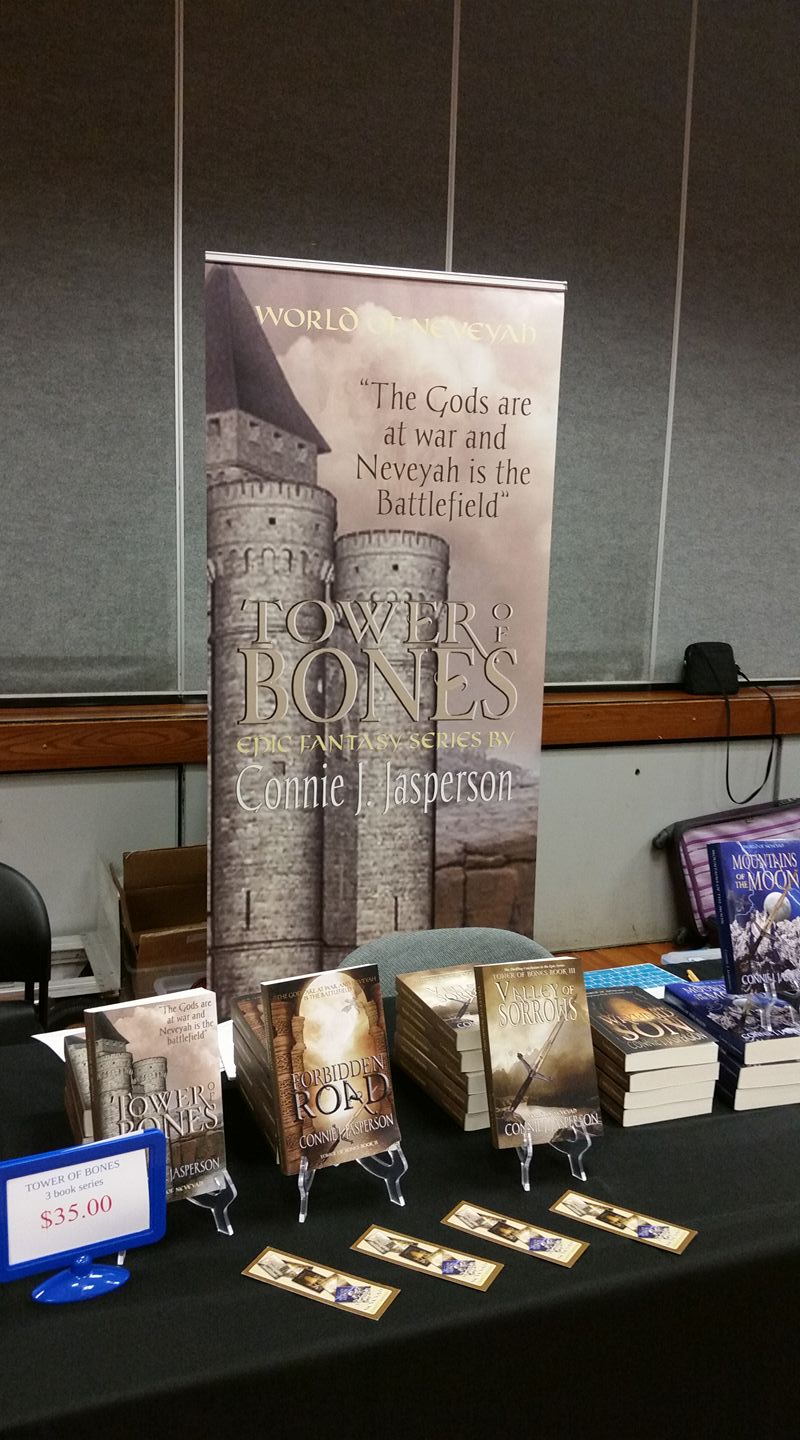

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you.

Nowadays, I am rarely able to do in-person events due to family constraints, but I used to do four events a year. However, I have some tips to help ease the path for you. The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins.

Investing in some large promotional graphics, such as a retractable banner, is a good idea. A large banner is a great visual to put behind your chair. A second banner for the front of the table looks professional but requires some fiddling with pins. Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

Make your display attractive, but I suggest you keep it simple. People will be able to see what you are selling, and the more fiddly things you add to your display, the longer setup and teardown will take. The shows and conferences I have attended offered plenty of time for this, but I’ve heard that some of the big-name conventions require you to be in or out in two hours or less.

The posts I wrote for that first attempt at blogging were pathetic attempts to write about current affairs and politics as a journalist, which is something that has never interested me. I was lucky if I managed to post one piece a month and had no readers or followers.

The posts I wrote for that first attempt at blogging were pathetic attempts to write about current affairs and politics as a journalist, which is something that has never interested me. I was lucky if I managed to post one piece a month and had no readers or followers. Books.

Books. I’ve made many friends through this writing adventure. I now know people from all over the world who I may never meet in person but who I am fond of, nevertheless.

I’ve made many friends through this writing adventure. I now know people from all over the world who I may never meet in person but who I am fond of, nevertheless. Some people worry about plagiarism, and in this world of AI and entitlement, it’s a valid concern. To my knowledge, I have never been plagiarized. I have a notice clearly in the sidebar on my website that the content is copyrighted.

Some people worry about plagiarism, and in this world of AI and entitlement, it’s a valid concern. To my knowledge, I have never been plagiarized. I have a notice clearly in the sidebar on my website that the content is copyrighted. Life in the Realm of Fantasy has evolved over the years because I have changed and matured as an author.

Life in the Realm of Fantasy has evolved over the years because I have changed and matured as an author. I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction.

I write what I am in the mood to read, so my genre is usually a fantasy of one kind or another. However, I sometimes go nuts and write women’s fiction. But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters.

But regardless of the genre, the basic premise of any story can be answered in eight questions that we will ask of the characters. And thus Julian Lackland and Lady Mags were born, and Huw the Bard and Golden Beau. But they needed a place to live, so along came Billy Ninefingers, captain of the Rowdies, and his inn, Billy’s Revenge. When I first met Billy and his colorful crew of mercenaries, I was hooked. I had to write the tale that became three novels: Julian Lackland, Billy Ninefingers, and Huw the Bard.

And thus Julian Lackland and Lady Mags were born, and Huw the Bard and Golden Beau. But they needed a place to live, so along came Billy Ninefingers, captain of the Rowdies, and his inn, Billy’s Revenge. When I first met Billy and his colorful crew of mercenaries, I was hooked. I had to write the tale that became three novels: Julian Lackland, Billy Ninefingers, and Huw the Bard.