Many authors are just starting out and have never written anything longer than a memo or a tweet. Once that first manuscript is finished, they will self-edit it. But what if they didn’t have the luxury of a college education in journalism? Many new writers don’t know how to write a readable sentence or what constitutes a paragraph.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

Most public schools in the US no longer teach creative writing. While some do have some writing classes, the majority of students leave school with a minimal understanding of basic grammar mechanics.

- They know when they read something that is poorly written, but they don’t know what grammar error makes it wrong. It just feels awkward, so they stop reading.

We who love to read know good writing when we read it. We might have the idea for the best story and the dedication and desire to write it.

However, getting our thoughts onto paper so other readers can enjoy it is not our best skill—yet.

But it soon will be. First, we must think of punctuation as the traffic signal that keeps the words flowing and the intersections manageable.

Trying to learn from a grammar manual can be complicated. I learned by reading the Chicago Manual of Style, which is the rule book for American English. Most editors in the large traditional publishing houses refer to this book when they have questions.

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in Bryan A. Garner’s Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. This is a resource with all the answers to questions about grammar and sentence structure. It takes the Chicago Manual of Style and boils it down to just the grammar.

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in Bryan A. Garner’s Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. This is a resource with all the answers to questions about grammar and sentence structure. It takes the Chicago Manual of Style and boils it down to just the grammar.

There are other style guides, each of which is tailored to a particular kind of writing, such as the AP manual for journalism and the Gregg manual for business writing. The CMoS is specifically for creative writing, such as fiction, memoirs, and personal essays, but also includes business and journalism rules.

However, the basic rules are simple.

Punctuation seems complicated because some advanced usages are open to interpretation. In those cases, how you habitually use them is your voice. Nevertheless, the foundational laws of comma use are not open to interpretation.

Consistently follow these rules, and your work will look professional.

First, commas and the fundamental rules for their use exist for a reason. If we want the reading public to understand our work, we need to follow them.

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

- Never insert commas “where you take a breath” because everyone breathes differently.

- Do not insert commas where you think it should pause because every reader sees the pauses differently.

Second: How do we use commas and coordinating conjunctions?

A comma should be used before these conjunctions: and, but, for, nor, yet, or, and so to separate two independent clauses. They are called coordinating conjunctions because they join two elements of equal importance.

However, we don’t always automatically use a comma before the word “and.” This is where it gets confusing.

Compound sentences combine two separate ideas (clauses) into one compact package. A comma should be placed before a conjunction only if it is at the beginning of an independent clause. So, use the comma before the conjunction (and, but, or) if the clauses are standalone sentences. If one of them is not a standalone sentence, it is a dependent clause, and you do not add the comma.

Take these two sentences: She is a great basketball player. She prefers swimming.

- If we combine them this way, we add a comma: She is a great basketball player, but she prefers swimming.

- If we combine them this way, we don’t: She is a great basketball player but prefers swimming.

The omission of one pronoun makes the difference.

You do not join unrelated independent clauses (clauses that can stand alone as separate sentences) with commas as that creates a rift in the space/time continuum: the Dreaded Comma Splice.

Boris kissed the hem of my garment, the dog likes to ride shotgun.

The dog has little to do with Boris other than the fact they both worship me. The same thought, written correctly:

Boris kissed the hem of my garment.

The dog likes to ride shotgun.

The dog riding shotgun is an independent clause and does not relate at all to Boris and his adoration of me. It should be in a separate paragraph. If you want Boris and the dog in the same sentence, you must rewrite it:

Boris and the dog worship me, and both like to ride shotgun.

Third, a semicolon in an untrained hand is a needle to the eye of the reader. Use them only when two standalone sentences or clauses are short and relate directly to each other.

Some people (including Microsoft Word) think a semicolon signifies an extra-long pause but not a hard ending. The Chicago Manual of Style and Bryan A Garner say that belief is wrong. Don’t blindly accept what Spellcheck tells you!

Semicolons join short independent clauses that can stand alone but which relate to each other. When do we use semicolons? Only when two clauses are short and are complete sentences that relate to each other. Here are two brief sentences that would be too choppy if left separate.

-

The door swung open at a touch. Light spilled into the room. (2 related short standalone sentences.)

-

The door swung open at a touch; light spilled into the room. (2 related short sentences joined by a semicolon.)

-

The door swung open at a touch, and light spilled into the room. (1 compound sentence made from 2 related standalone clauses joined by a comma and a conjunction.) (A connector word.)

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

I generally try to find alternatives to semicolons. they’re too easily abused because Microsoft Word and most people don’t know how to use them.

Fourth: Colons. These head lists but are more appropriate for technical writing. Colons are rarely needed in narrative prose. In technical writing, you might say something like:

For the next step, you will need:

- four bolts,

- two nail files,

- one peach, whole and unpeeled.

Technically speaking, I have no idea what they are building, but I can’t wait to see it!

Fifth: Oxford commas, also known as serial commas. This is the one war authors will never win or find common ground, a true civil war.

When listing a string of things in a narrative, we separate them with commas to prevent confusion. I like people to understand what I mean, so I always use the Oxford Comma/Serial Comma.

If there are only two things (or ideas) in a list, they do not need to be separated by a comma. If there are more than two ideas, the comma should be used as it would be used in a list.

We sell dogs, cats, rabbits, and picnic tables.

Why do we need clarity? You might know what you mean, but not everyone thinks the same way.

I accept this Nebula award and thank my late parents Irene Luvaul and Poseidon.

That sentence might make sense to some readers, but not in the way I intended. The intention of it is to thank my late parents, my editor, and the God of the Sea. If I don’t thank Poseidon, he’ll pitch a fit.

I accept this Nebula award and thank my late parents, Bob and Marge, my editor Irene Luvaul, and Poseidon, the God of the Sea.

Sixth: We use a comma after common introductory clauses.

After dark, Boris would change into his bat form and go hunting for enchiladas.

Seventh: Punctuating dialogue: All punctuation goes inside the quote marks.

- A comma follows the spoken words, separating the dialogue from the speech tag.

- The clause containing the dialogue is enclosed, punctuation and all, within quotes.

- The speech tag is the second half of the sentence, and a period ends the entire sentence.

The editor said, “I agree with those statements.”

If the dialogue is split by the speech tag, do not capitalize the first word in the second half.

“I agree with those statements,” said the editor, “but I wish you’d stop repeating yourself.”

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

If you follow these seven simple rules, your work will be readable. If your story is creative and well-written, it will be acceptable to acquisitions editors.

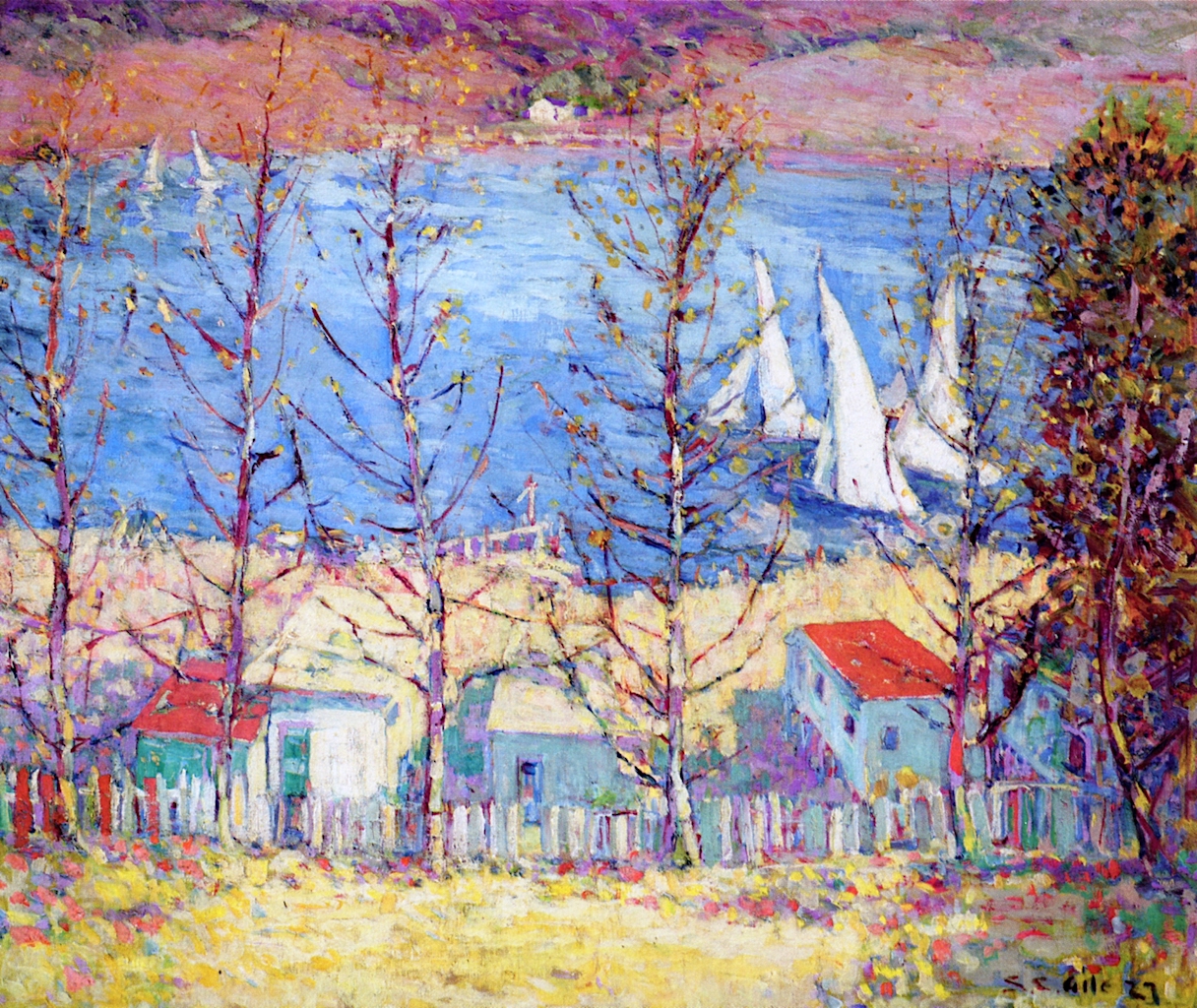

Artist: Mário Navarro da Costa (1883-1931)

Artist: Mário Navarro da Costa (1883-1931) So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like

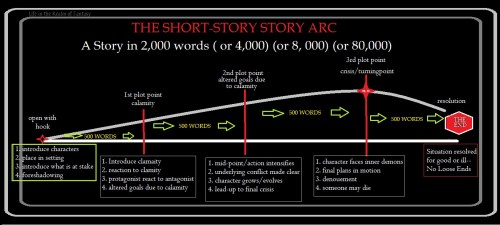

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like  The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it?

The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it? Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen.

Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen. Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories. Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it.

Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it. Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition.

Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition. When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance.

When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance. To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot!

To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot! Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript.

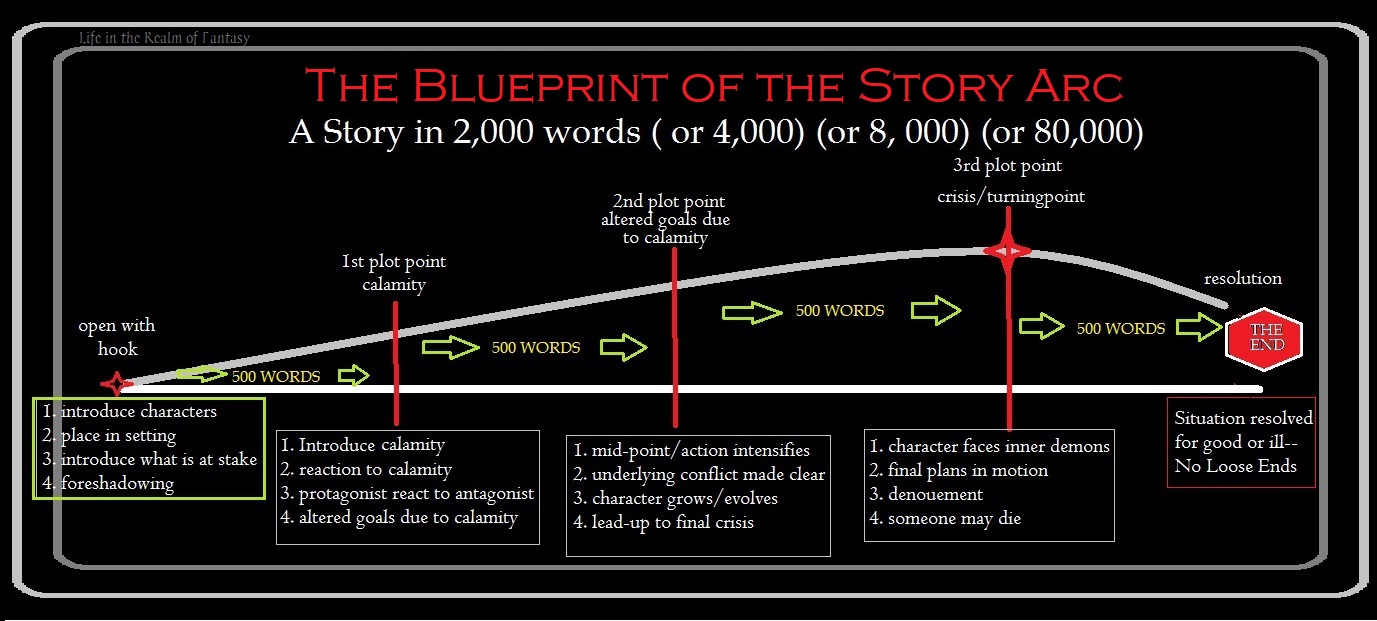

I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript. 40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark.

40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark. In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery.

In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery. I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut.

I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut. Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings.

Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings. The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson

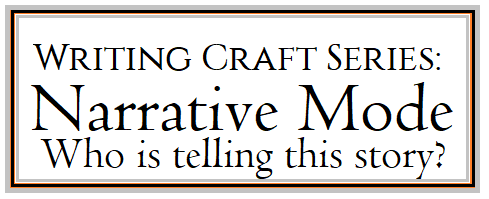

The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us.

When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us. Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

“I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides it was a secret.”

“I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides it was a secret.”

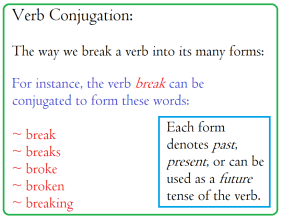

In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story.

In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story. When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show.

When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show. The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear.

The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear. If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others.

If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others. Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader.

Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader. I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person.

I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person.