In the previous post, we talked about scene framing. Scenes are word pictures, portraits of a moment in a character’s life framed by the backdrop of the world around them. Everything depicted in that scene has meaning.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

Transitions bookend each scene, and the way we use those transitions determines the importance of the passage. The bookends determine the narrative’s pacing.

Transition scenes get us smoothly from one event or conversation to the next. They push the plot forward. Action, transition, action, transition—this is pacing.

The pacing of a story is created by the rise and fall of action.

- Action: Our characters do

- Visuals: We see the world through their eyes; they show us something.

- Conversations: They tell us something, and the cycle begins again.

Do.

Show.

Tell.

I picked up my kit and looked around. No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye. The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance.

The character in the above transition scene completes an action in one scene and moves on to the next event. It reveals his mood and some of his history in 46 words and propels him into the next scene.

He does something: I picked up my kit and looked around.

He shows us something: No wife to kiss goodbye, no real home to leave behind, nothing of value to pack. Only the need to bid Aeoven and my failures goodbye.

He tells us something: The quiet snick of the door closing behind me sounded like deliverance.

The door has closed, there is no going back, and he is now in the next action sequence. We find out who and what is waiting for him on the other side of that door.

All fiction has one thing in common regardless of the genre: characters we can empathize with are thrown into chaos with a plot.

Remember the blank wall from above and the random pictures placed on it?

Our narrative begins as a blank wall strewn with pictures. We take those pictures and add transition pictures to create a coherent story out of the visual chaos.

This is where project management comes into play—we assign an order to how the scenes progress.

- Processing the action.

- Action again.

- Processing/regrouping.

Our job is to make the transitions subliminal. We are constantly told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” To be honest, I know a lot of words, and wasting them is my best skill.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

What makes a memorable story? In my opinion, the emotions it evoked are why I loved a particular novel. The author allowed me to process the events and gave me a moment of rest and reflection between the action.

I was with the characters when they took a moment to process what had just occurred. That moment transitions us to the next scene.

These information scenes are vital to the reader’s understanding of why these events occur. They show us what must be done to resolve the final problem.

The transition is also where you ratchet up the emotional tension. As shown in the example above, introspection offers an opportunity for clues about the characters to emerge. A “thinking scene” opens a window for the reader to see who they are and how they react. It illuminates their fears and strengths, and makes them seem real and self-aware.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals.

With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. (Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.)

Fade-to-black is a time-honored way of moving from one event to the next. However, I dislike using fade-to-black scene breaks as transitions within a chapter. Why not just start a new chapter once the scene has faded to black?

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

Chapter breaks are transitions. I have found that as I write, chapter breaks fall naturally at certain places.

Every author develops habits that either speed up or slow down the workflow. I use project management skills to keep every aspect of life moving along smoothly, and that includes writing.

In my world, the first draft of any story or novel is really an expanded outline. It is a series of scenes that have characters talking or doing things. But those scenes are disconnected. The story is choppy, nothing but a series of events. All I was concerned about was getting the story written from the opening scene to the last page and the words “the end.”

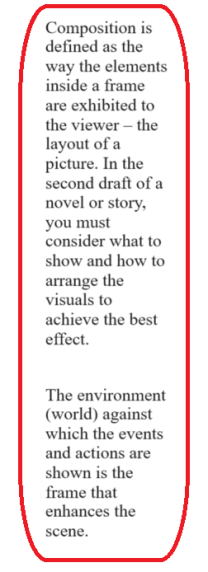

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

Yes, that first draft manuscript was finished in the regard that it had a beginning, middle, and ending.

But I was too involved and couldn’t see that while each scene was a picture of a moment in time, it was only a skeleton, a pile of bones.

By setting it aside for a while, I’m able to see it still needs muscles and heart and flesh. Transitions layer those elements on, creating a living, breathing story.

Credits and attributions:

IMAGE: Title: The Sciences and Arts

Artist: Hieronymous Francken II (1578–1623) or Adriaen van Stalbemt (1580–1662)

Genre: interior view

Date: between 1607 and 1650

Medium: oil on panel

Dimensions: height: 117 cm (46 in); width: 89.9 cm (35.3 in)

Collection: Museo del Prado

Notes: This work’s attribution has not been determined with certainty with some historian preferring Francken over van Stalbemt. See Sotheby’s note. Sold 9 July 2014, lot 57, in London, for 422,500 GBP

Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Stalbent-ciencias y artes-prado.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Stalbent-ciencias_y_artes-prado.jpg&oldid=699790256 (accessed March 12, 2024).

Artist: Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Artist: Claude Monet (1840–1926)

But how do we recognize when a moment of action has true dramatic potential? We try to inject action and emotion into our scenes, but some dramatic events don’t advance the story.

But how do we recognize when a moment of action has true dramatic potential? We try to inject action and emotion into our scenes, but some dramatic events don’t advance the story. Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel

Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel  I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places.

I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places.

I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

In his book

In his book

When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes.

When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes. I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love.

I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love. Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)

Artist: Camille Pissarro (1830–1903)![Stephen Hawking, Star Child, By NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/stephen_hawking-starchild.jpg?w=500)

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

But the scenes themselves are pictures within the larger picture of the story arc. Think of the story arc as a blank wall. We place the scenes on that blank wall in the order we want them, but without transition scenes, these moments in time appear random, as if they don’t go together.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next.

Our bookend scenes are not empty words. They should reveal something and push us toward something unknown. They lay the groundwork for what comes next. One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black.

One of my favorite authors sometimes has chapters of only five or six hundred words, keeping each character thread separate and flowing well. A hard scene break with a new chapter is my preferred way to end a nice, satisfying fade-to-black. The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next.

The second draft is where the real work begins. I set the first draft aside for several weeks and then go back to it. I look at my outline to make sure the events fall in the proper order. At that point, I can see how to write the transitions to ensure each scene flows naturally into the next. In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment.

In a novel or story, each scene occurs within the framework of the environment. The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants.

The Dragonriders of Pern series is considered science fiction because McCaffrey made clear at the outset that the star (Rukbat) and its planetary system had been colonized two millennia before, and the protagonists were their descendants. The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted.

The scenes we are looking at today have two distinct environments to frame them. In both settings, the surroundings do the dramatic heavy lifting. This chapter is filled with emotion, high stakes, and rising dread for the sure and inevitable tragedy that we hope will be averted. Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured.

Sallah enters the shuttle just as the airlock door closes, catching and crushing her heel. She manages to pull it out so that she isn’t trapped, but she is severely injured. This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.

This is an incredibly emotional scene: we are caught up in her determination to seize this only chance, using her last breaths to get the information about the thread spores to the scientists on the ground.![While reading the newspaper news by H. A. Brendekilde [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/h-_a-_brendekilde_-_mens_du_lc3a6ser_avisen_nyheder_1912.jpg?w=500)

![Worn Out by H. A. Brendekilde [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://conniejjasperson.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/h-_a-_brendekilde_-_udslidt_1889.jpg?w=500)

So, let’s take a look at theme, the thread that binds emotions and points of no return together. It’s time to take another look at how

So, let’s take a look at theme, the thread that binds emotions and points of no return together. It’s time to take another look at how  Saunders gives us the character of Ray Abnesti, a scientist developing pharmaceuticals and using convicted felons as guinea pigs as part of the justice system. The wider world has forgotten about those whose crimes deserve punishment, whose fate goes unknown and unlamented.

Saunders gives us the character of Ray Abnesti, a scientist developing pharmaceuticals and using convicted felons as guinea pigs as part of the justice system. The wider world has forgotten about those whose crimes deserve punishment, whose fate goes unknown and unlamented. Then there is the theme of compassion. Abnesti explores love vs. lust for his own amusement. The different drugs Jeff is given prove that both are illusionary and fleeting. Yet Saunders implies that the truth of love is compassion. Jeff’s final action shows us that he is a man of compassion.

Then there is the theme of compassion. Abnesti explores love vs. lust for his own amusement. The different drugs Jeff is given prove that both are illusionary and fleeting. Yet Saunders implies that the truth of love is compassion. Jeff’s final action shows us that he is a man of compassion. A common theme in science fiction is the use of drugs to alter people’s behavior and control them emotionally. That theme is explored in detail here, ostensibly as a means to do away with prisons and reform prisoners. But really, these experiments are for Abnesti, a psychopath, to exercise his passion for the perverse and inhumane and for him to have power over the helpless.

A common theme in science fiction is the use of drugs to alter people’s behavior and control them emotionally. That theme is explored in detail here, ostensibly as a means to do away with prisons and reform prisoners. But really, these experiments are for Abnesti, a psychopath, to exercise his passion for the perverse and inhumane and for him to have power over the helpless. This short story was as powerful as any novel I’ve ever read, proving that a good story stays with the reader long after the final words have been read, no matter the length. His questions resonate, asking us to think about our true motives.

This short story was as powerful as any novel I’ve ever read, proving that a good story stays with the reader long after the final words have been read, no matter the length. His questions resonate, asking us to think about our true motives. But what happens when a few insignificant cracks appear in that construction? What is the point of no return for the people living downstream?

But what happens when a few insignificant cracks appear in that construction? What is the point of no return for the people living downstream? We must identify this plot point, and by mentioning it in passing, we make it subtly clear to the reader that this moment in time will have far-reaching consequences. Knowing something might be wrong and seeing the workers unaware of a problem ratchets up the tension.

We must identify this plot point, and by mentioning it in passing, we make it subtly clear to the reader that this moment in time will have far-reaching consequences. Knowing something might be wrong and seeing the workers unaware of a problem ratchets up the tension. Nick Carraway, the

Nick Carraway, the  Fitzgerald is deliberately unclear if this act is deliberate or accidental—the murkiness of Daisy’s intent and the chaos of that incident lend an atmosphere of uncertainty to the narrative. If Nick had turned back at any of the above-listed points, Daisy wouldn’t have been driving Gatsby’s yellow Rolls Royce and wouldn’t have killed Myrtle in a hit-and-run accident.

Fitzgerald is deliberately unclear if this act is deliberate or accidental—the murkiness of Daisy’s intent and the chaos of that incident lend an atmosphere of uncertainty to the narrative. If Nick had turned back at any of the above-listed points, Daisy wouldn’t have been driving Gatsby’s yellow Rolls Royce and wouldn’t have killed Myrtle in a hit-and-run accident. When I am writing a first draft, the crucial turning points don’t always make themselves apparent. It’s only when I have begun revisions that I see the opportunities for mayhem that my subconscious mind has embedded in the narrative.

When I am writing a first draft, the crucial turning points don’t always make themselves apparent. It’s only when I have begun revisions that I see the opportunities for mayhem that my subconscious mind has embedded in the narrative.