I think of writing as a muscle of sorts, working the way all other muscles do. Our bodies are healthiest when we exercise regularly, and with respect to our creativity, writing works the same way.

Daily writing becomes easier once you make it a behavioral habit. The more frequently you write, the more confident you become. Spend a small amount of time writing every day and you will develop discipline.

Daily writing becomes easier once you make it a behavioral habit. The more frequently you write, the more confident you become. Spend a small amount of time writing every day and you will develop discipline.

If you hope to finish writing a book, personal discipline is essential.

Every morning, I take the time to write a random short scene or vignette. Some become drabbles, others short stories, but most are just for exercise. Writing 100-word stories is a good way to create characters you can use in other works.

Some of the best work I’ve ever read was in the form of extremely short stories. Authors grow in their craft and gain different perspectives with each short story and essay they write. Each short piece increases your ability to tell a story with minimal exposition.

This is especially true if you write the occasional drabble—a whole story in 100 words or less. These practice shorts serve several purposes, but most importantly, they grow your habit of writing new words every day.

Writing such short fiction forces the author to develop an economy of words. You have a finite number of words to tell what happened, so only the most crucial information will fit within that space.

Writing drabbles means your narrative will be limited to one or two characters. There is no room for anything that does not advance the plot or affect the story’s outcome.

The internet is rife with contests for drabbles, some offering cash prizes. A side-effect of building a backlog of short stories is the supply of ready-made characters and premade settings you have to draw on when you need a longer story to submit to a contest.

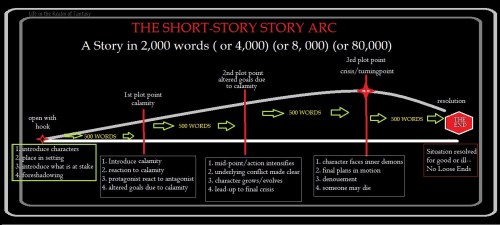

Below is a graphic for breaking down the story arc of a 2,000-word story. Writing a 100-word story takes less time than writing a 2,000-word story, but all writing is a time commitment.

When writing a drabble, you can expect to spend an hour or more getting it to fit within the 100-word constraint.

To write a drabble, we need the same fundamental components as we do for a longer story:

- A setting

- One or more characters

- A conflict

- A resolution.

First, we need a prompt, a jumping-off point. We have 100 words to write a scene that tells the entire story of a moment in a character’s life.

Some contests give whole sentences for prompts, others offer one word, and others may offer no prompt at all.

A prompt is a word or visual image that kick starts the story in your head. If you need an idea, go to 700+ Weekly Writing Prompts.

A prompt is a word or visual image that kick starts the story in your head. If you need an idea, go to 700+ Weekly Writing Prompts.

If a contest has a rigid word count requirement, it’s best to divide the count into manageable sections. I use a loose outline to break short stories into acts with a certain number of words for each increment, as illustrated in the previous graphic, the short-story story arc.

A drabble works the same way.

We break down the word count to make the story arc work for us instead of against us. We have about 25 words to open the story and set the scene, about 50 – 60 for the heart of the story, and 10 – 25 words to conclude it.

If you are too focused on your novel to think about other works, spend fifteen minutes writing info dumps about character history and side trails to nowhere. That is an excellent way to build background files for your world-building and character development and keeps the info dumps separate and out of the narrative.

Also, you have the chance to identify the themes and subthemes you can expand on to add depth to your narrative.

Theme is vastly different from the subject of a work. Theme is an underlying idea, a thread that is woven through the story from the beginning to the end.

An example I’ve mentioned before is the movie franchise Star Wars. The subject of those movies is the battle for control of the galaxy between the Galactic Empire and the Rebel Alliance. Two of the themes explored in those films are the bonds of friendship and the gray area between good and evil—moral ambiguity.

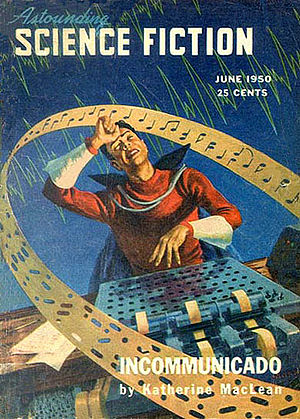

The best way to begin building your brand as an author is to submit your work to magazines and anthologies. But writing for magazines and anthologies is different than writing novels. Some aspects of short story construction are critical and must be planned for in advance, important elements of craft that show professionalism.

When you choose to submit to an open call for themed work, your work must demonstrate your understanding of what is meant by the word “theme” as well as your ability to write clean and compelling prose.

For practice, try picking a theme and thinking creatively. Think a little wide of the obvious tropes (genre-specific, commonly used plot devices and archetypes). Look for an original angle that will play well to that theme, and then go for it.

Most of my own novels fit in epic or medieval fantasy genres. They are based on the hero’s journey, detailing how events and experiences shape the characters’ reactions and personal growth. The hero’s journey is a theme that allows me to employ the sub-themes of brother/sisterhood and love of family.

These concepts are heavily featured in the books that inspired me, and so they find their way into my writing.

To support the theme, you must add these layers:

- character studies

- allegory

- imagery

These three layers must all be driven by the central theme and advance the story arc.

When you write to a strict word count limit, every word is precious and must be used to the greatest effect. By shaving away the unneeded info in the short story, the author has more room to expand on the story’s theme and how it supports the plot.

When you write to a strict word count limit, every word is precious and must be used to the greatest effect. By shaving away the unneeded info in the short story, the author has more room to expand on the story’s theme and how it supports the plot.

Save your drabbles and short scenes in a clearly labeled file for later use. Each one has the potential to be a springboard for writing a longer work or for submission to a drabble contest in its proto form.

Good drabbles are the distilled souls of novels. They contain everything the reader needs to know about that moment and makes them wonder what happened next.

Write at least 100 new words every day. Write even if you have nothing to say. Write a wish list, a grocery list, or a sonnet—but no matter what form the words take, write. The act of writing new words on a completely different project can break you out of writer’s block—it nudges your creative mind.

To know that, you must know the genre of the work you are trying to sell. So, what exactly are genres? Publisher and author

To know that, you must know the genre of the work you are trying to sell. So, what exactly are genres? Publisher and author  Mainstream (general) fiction—Mainstream fiction is a general term that publishers and booksellers use to describe works that may appeal to the broadest range of readers and have some likelihood of commercial success. Mainstream authors often blend genre fiction practices with techniques considered unique to literary fiction. It will be both plot- and character-driven and may have a style of narrative that is not as lean as modern genre fiction but is not too stylistic either. The novel’s prose will at times delve into a more literary vein than genre fiction. The story will be driven by the events and actions that force the characters to grow.

Mainstream (general) fiction—Mainstream fiction is a general term that publishers and booksellers use to describe works that may appeal to the broadest range of readers and have some likelihood of commercial success. Mainstream authors often blend genre fiction practices with techniques considered unique to literary fiction. It will be both plot- and character-driven and may have a style of narrative that is not as lean as modern genre fiction but is not too stylistic either. The novel’s prose will at times delve into a more literary vein than genre fiction. The story will be driven by the events and actions that force the characters to grow. Fantasy is a fiction genre that commonly uses magic and other supernatural phenomena as a primary plot element, theme, or setting. Like sci-fi and literary fiction, fantasy has its share of snobs when it comes to defining the sub-genres. The tropes are:

Fantasy is a fiction genre that commonly uses magic and other supernatural phenomena as a primary plot element, theme, or setting. Like sci-fi and literary fiction, fantasy has its share of snobs when it comes to defining the sub-genres. The tropes are: Literary fiction can be adventurous with the narrative. The style of the prose has prominence and may be experimental, requiring the reader to go over certain passages more than once. Stylistic writing, heavy use of allegory, the deep exploration of themes and ideas form the core of the piece.

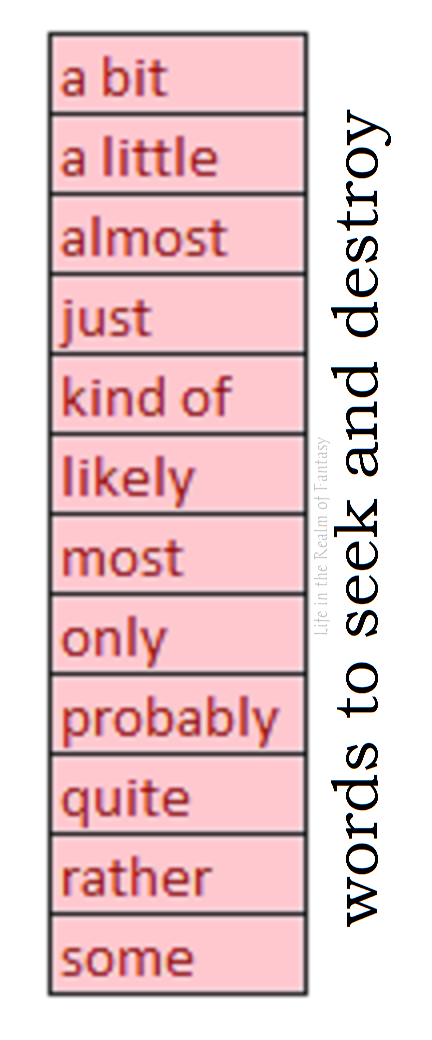

Literary fiction can be adventurous with the narrative. The style of the prose has prominence and may be experimental, requiring the reader to go over certain passages more than once. Stylistic writing, heavy use of allegory, the deep exploration of themes and ideas form the core of the piece. One step on the slippery slope of passive prose is the overuse of

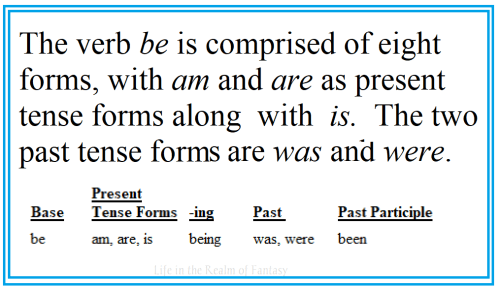

One step on the slippery slope of passive prose is the overuse of  I think the habit of using one of the eight forms of the word be is more one of

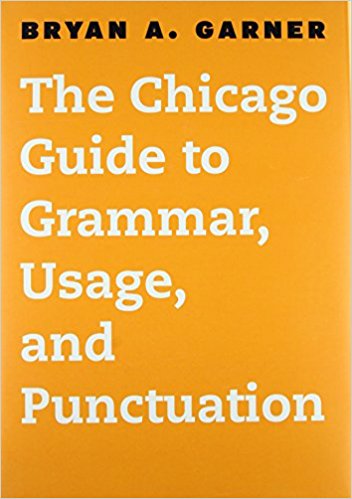

I think the habit of using one of the eight forms of the word be is more one of  The whole thing looks quite complicated on the surface, but it doesn’t have to be. We must begin assembling our writers’ toolbox. One important tool is Bryan Garner’s

The whole thing looks quite complicated on the surface, but it doesn’t have to be. We must begin assembling our writers’ toolbox. One important tool is Bryan Garner’s  I say cut back, not eliminate. Despite the misguided efforts of many gurus and Microsoft Word to erase all forms of ‘to be’ from the English language and replace it with ‘is,’ there are times when only a subjunctive will do the job.

I say cut back, not eliminate. Despite the misguided efforts of many gurus and Microsoft Word to erase all forms of ‘to be’ from the English language and replace it with ‘is,’ there are times when only a subjunctive will do the job. A critique group may tear your work apart, which stings a wounded ego. But we grow from this experience. We learn that opinions are subjective, and writers are thin-skinned creatures. We develop a thicker skin and muck on.

A critique group may tear your work apart, which stings a wounded ego. But we grow from this experience. We learn that opinions are subjective, and writers are thin-skinned creatures. We develop a thicker skin and muck on. By creating small arcs in the form of scenes, we offer the reader the chance to experience the rise and fall of tension, the life-breath of the novel.

By creating small arcs in the form of scenes, we offer the reader the chance to experience the rise and fall of tension, the life-breath of the novel. Code words are the author’s first draft

Code words are the author’s first draft  Thought (Introspection):

Thought (Introspection): That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see.

That is true of every aspect of a scene—it must reveal something we didn’t know and push the story forward toward something we can’t quite see. Novels consist of a string of moments united by a common theme. These scenes combine to form a story when you put them together in the right order and link them with a plot featuring a compelling protagonist who must overcome adversity.

Novels consist of a string of moments united by a common theme. These scenes combine to form a story when you put them together in the right order and link them with a plot featuring a compelling protagonist who must overcome adversity.

In my last post, I talked about the good and bad aspects of two editing programs that I am familiar with, the things they do and don’t help us identify in our work. One more thing these wonderful programs can’t help us with is identifying bloated backstory.

In my last post, I talked about the good and bad aspects of two editing programs that I am familiar with, the things they do and don’t help us identify in our work. One more thing these wonderful programs can’t help us with is identifying bloated backstory. Look at the first scene of your manuscript. Ask yourself three questions.

Look at the first scene of your manuscript. Ask yourself three questions. I look at each conversation and assess how many words are devoted to each character’s statement and response. Then, when I come to a passage that is inching toward a monologue, I ask myself, “what can be cut that won’t affect the flow of the story or gut the logic of the plot?”

I look at each conversation and assess how many words are devoted to each character’s statement and response. Then, when I come to a passage that is inching toward a monologue, I ask myself, “what can be cut that won’t affect the flow of the story or gut the logic of the plot?” I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t.

I do use Grammarly—but also, I don’t. Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error.

Spellcheck doesn’t understand context, so if a word is misused but spelled correctly, it may not alert you to an obvious error. New writers should invest in the

New writers should invest in the  Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later.

Even editors must have their work seen by other eyes. My blog posts are proof of this as I am the only one who sees them before they are posted. Even though I write them in advance, go over them with two editing programs, and then look at them again before each post goes live, I still find silly errors two or three days later. If you have decided something is a “crutch word,” examine the context. Inadvertent repetitions of certain words are easy to eliminate once we see them with a fresh eye.

If you have decided something is a “crutch word,” examine the context. Inadvertent repetitions of certain words are easy to eliminate once we see them with a fresh eye. From my earliest childhood, I always thought of myself as a writer. I just didn’t know how to write anything longer than a poem or a song in such a way that it was readable.

From my earliest childhood, I always thought of myself as a writer. I just didn’t know how to write anything longer than a poem or a song in such a way that it was readable. One day in 1990, I stumbled upon a book offered in the

One day in 1990, I stumbled upon a book offered in the  Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining The Pacific Northwest Writers Association and going to their conferences.

Spend the money to go to conventions and attend seminars. You will learn so much about the craft of writing, the genre you write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things you can only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining The Pacific Northwest Writers Association and going to their conferences. Six: My final suggestion is this: even though you are writing that novel, keep writing short stories too.

Six: My final suggestion is this: even though you are writing that novel, keep writing short stories too. When I have asked a beta reader to read a section of my work, they sometimes flag a paragraph as unclear. It might make perfect sense to me, but if I am the only one who understands it, it’s time to tear that paragraph down to see if each sentence can stand on its own.

When I have asked a beta reader to read a section of my work, they sometimes flag a paragraph as unclear. It might make perfect sense to me, but if I am the only one who understands it, it’s time to tear that paragraph down to see if each sentence can stand on its own. I don’t want to introduce vagueness into my work. Just because I like what I wrote doesn’t mean it has to stay in the finished product. Maybe I don’t see that it’s confusing, but my friends who read my raw manuscripts will.

I don’t want to introduce vagueness into my work. Just because I like what I wrote doesn’t mean it has to stay in the finished product. Maybe I don’t see that it’s confusing, but my friends who read my raw manuscripts will. Who is the enemy, the true architect of that conflict? At this point, we may have a name, but who are they really?

Who is the enemy, the true architect of that conflict? At this point, we may have a name, but who are they really? “God! You honestly believe I’m stupid.” Despite his anger, Beau kept his voice low. “There’s no reasoning with you. You’re convinced I’m besotted and Julian is barking mad. Get out of my way! I feel like hurting you.” He pushed past Huw, saying, “Go home, since you have so little faith in me.” He opened the door, intending to leave.

“God! You honestly believe I’m stupid.” Despite his anger, Beau kept his voice low. “There’s no reasoning with you. You’re convinced I’m besotted and Julian is barking mad. Get out of my way! I feel like hurting you.” He pushed past Huw, saying, “Go home, since you have so little faith in me.” He opened the door, intending to leave. In other stories, there is the nebulous antagonist. This could be the faceless behemoth of corporate greed, characterized by one or two representatives who may be portrayed as caricatures. In some

In other stories, there is the nebulous antagonist. This could be the faceless behemoth of corporate greed, characterized by one or two representatives who may be portrayed as caricatures. In some  A true villain is motivated, logical in their reasoning, and is utterly convinced of their moral high ground. They are creatures of emotion and have a backstory. As the author and their lawyer, you must know what their narrative is if you want to increase the risk for the protagonist.

A true villain is motivated, logical in their reasoning, and is utterly convinced of their moral high ground. They are creatures of emotion and have a backstory. As the author and their lawyer, you must know what their narrative is if you want to increase the risk for the protagonist.