Before we begin, I hope you’ll bear with me as I learn to use the unnecessarily complicated dashboard WordPress calls “Gutenberg.” For a person who relies on images as much as I do, this isn’t a good fit, but I will make it work. They have removed the Admin Dashboard, which was perfect for uploading and positioning images and text. Please bear with me as I find ways to write my posts despite being forced to use the least intuitive dashboard the geniuses at WordPress could have come up with.

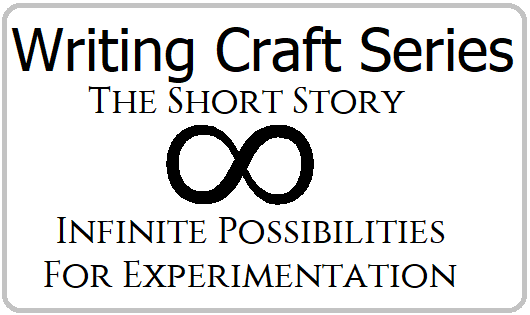

When it comes to learning how to write, experimentation is good. The best form for learning learning to write in different styles and genres is the short story.

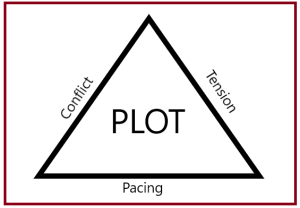

Last week, we discussed why authors should write short stories and looked at one way to lay out the story arc. There are other ways, but that is my most commonly used method. If you are curious, this is the post: Gaining Readers Through Writing Short Stories.

This week we are going deeper into the many elements of writing a good, gripping story. Most of these features will be found in any length of story, from drabbles to novels. Today we are still focusing on getting all the elements into a piece that is less than 2,000 words long.

Before we go on, we need to remember that setting, atmosphere, and mood are intertwined.

Today’s example is from The Iron Dragon, a 1,025-word story I wrote during NaNoWriMo 2015. That was the year I focused on experimental writing, putting out at least one short story every day, and sometimes two.

The first paragraph of the Iron Dragon begins in the middle of a story:

Earl Aeddan ap Rhydderch turned his gaze from the mist to the strange iron road that emerged from it and then to where the road entered the cave. “Tell me again what happened.”

The opening sentences establish the story, set the scene, and introduce the first protagonist. The following three paragraphs show the world and establish the mood:

The peasant who had guided the earl and his men said, “The mist, the iron road, and the cave appeared yesterday, sir. We saw the beast entering its lair, and a fearful thing it is, too. No one dares to approach it, but the monster can be heard in there. It’s a most dreadful dragon — we found the carcass of a large wolf that had been torn to shreds, trampled until it was nigh unrecognizable.”

The man’s companion said, “Everyone knows wolves are Satan’s hounds. It must have angered its hellish master. We found it lying cast to one side of the Devil’s Road.”

Aeddan looked back to the iron road, seeing where it emerged from the mist. He walked to the low-hanging fog bank, seeing that the road vanished just after it entered the mist, leaving no marks upon the soil. He turned and strode back to the peasants. “I agree it’s the work of the Devil, but why does the Lord of Hell require an iron road that leads nowhere?”

The paragraphs that follow present the danger, the problem Aeddan must overcome:

A faint grumbling sounded beneath Aeddan’s feet. “A light! Look to the mist!” shouted one of his men.

Turning, Aeddan saw a white glow forming in the fog as if a large lamp approached from a great distance. “That’s no ordinary lantern. Mount up!” Moving quickly, he leaped into his saddle and turned his steed to face the demon.

A few sentences further on, I showed more of the world at the same time as I introduced the antagonist:

The light deep within the fog grew and strengthened, as did the rumbling noise. It waxed brilliant, and the earth shuddered as if beneath the pounding of a thousand hooves. Smoke filled the night air, reeking of the sulfurous Abyss, combined with a howling as cacophonous as the shrieks of all the damned in Hell.

What emerged from the mist was impossible — an Iron Dragon of immense height and girth.

At this point, Aeddan knows that he must resolve the problem and protect his people:

The fiery light emanating from the burning maw lit the night, and the ground shook as the beast roared and raced ever closer. As the beast sped toward him, a burning wind blowing straight out of Hell knocked Aeddan and his horse to the side of the Devil’s Road, and using that opportunity, the Iron Dragon thundered past him, heading into its lair.

Stunned, Aeddan scrambled to his feet, staring as the beast passed him by, the body taller than a house and long, like an unimaginably giant, demonic centipede. The length of the beast was incomprehensible, lit by the fire within and glowing with row upon row of openings. The faces of the damned, souls who’d been consumed by the ravening beast peered out as they flashed by. Sparks flew from its many hooves.

Terrified his men would be crushed by the immense creature, he shouted for them to back off, his voice drowned by the din.

There is more to Aeddan’s side of the story, of course. But in what you have read already, you have made some guesses and are already aware that this is a story with two sides. Aeddan’s point of view is not the entire story.

Again, we must set the scene and establish the mood and characters. Here we meet the second protagonist, an engine driver named Owen:

Mist shrouded the small valley just outside of the village of Pencader. Engine Driver Owen Pendergrass looked at his pocket watch and opened the logbook, noting the time and that they had just departed Pencader Station. He said to the fireman, Colin Jones, “We should be approaching the tunnel, though it’s hard to tell in this mist. We’re making good time despite the fog. We’ll be in Carmarthen on schedule.”

“Sir! Look just ahead! What…?” Colin pointed ahead.

A group of mounted men dressed as medieval knights, complete with lances lowered as if prepared to joust, appeared out of the mist, attempting to block their path. “God in heaven — what next!” Blowing the whistle to scare them off the tracks, Owen pulled the brake cord, but there was no way the train could stop soon enough. In no time at all, the train was upon the knights, scattering them and blowing past. Owen looked out the window to see if they’d survived, but they were gone as if they’d never been.

The final paragraphs wind it up. They also contribute to the overall atmosphere and setting of the second part of the story. The story in its entirety can be read here: The Iron Dragon. It is an imperfect story, but as a practice piece, it has good bones. I didn’t feel that particular piece was suitable for submission to a magazine or contest.

Word choices are essential in showing a world and creating an atmosphere that feels believable. I had challenged myself to write a story that told both sides of a frightening encounter in 1000 words, give or take a few. I also wanted to show two aspects of a place in Wales but tell one story as lived by two protagonists separated by twelve centuries and a multitude of legends.

This brings me back to the layout aspect of a short piece. Some speculative fiction stories work well when the flow of the story arc is shaped like an infinity sign, a figure-eight laying on its side: ∞

Instead of the usual bridge shape, the story arc begins in the middle, circles around, comes back to the middle, and circles around a different way. It ends where it began.

Writing short fiction offers me the chance to experiment with both style and genre. It challenges me to build a world in only a few words and still tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Sometimes what I turn out is worth sharing, and other times, not so much. The act of writing something different, a little outside my comfort zone, stretches my ability to “think widely.” It makes me a better reader as well as a better writer.

>>><<< >>><<< >>><<<

Credits and Attributions:

Excerpts from The Iron Dragon, by Connie J. Jasperson, ©2015-2021 All Rights Reserved.