When I get into revisions, I often find my characters seem two-dimensional. Certain passages stand out because the characters have life, an intensity that feels palpable.

Others, not so much.

I aspire to write like my heroes, authors who create characters who come alive. While I’m in that world, I see the people and their stories as sharply as the author intends.

I aspire to write like my heroes, authors who create characters who come alive. While I’m in that world, I see the people and their stories as sharply as the author intends.

Some of my work manages to find that happy place, but other passages feel flat, lacking spark. That is where I look at contrast – polarity. When I use polarity well, my narrative makes my editor happy.

I know I say this regularly, but word choice matters. How I choose to phrase a passage can make an immersive experience or throw the reader out of the book. Sometimes I am more successful than other times.

My goal is to make vivid sensory images for my readers, but not one that is hyper-dramatic and overblown. Subtlety in contrasts is as essential as painting a scene with sweeping polarities. They both add to the texture of the narrative but must be balanced for optimal pacing.

Poets understand and use polarity. John Keats used both polarities and similes in his work. The last stanza of To Autumn begins with this line:

“Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;”

We see one obvious polarity in that line, and also a sneaky one:

- Lives or dies is a clear polarity.

- Sinking implies heaviness, and Keats contrasted it with light wind, a less weighty, gentler sensory experience, the opposite of the weight of sinking.

Polarity gives the important elements strength. It provides texture but often goes unnoticed while it influences a reader’s perception.

Polarity gives the important elements strength. It provides texture but often goes unnoticed while it influences a reader’s perception.

The theme is the backbone of your story, a thread that binds the disparate parts together. Great themes are often polarized: good vs. evil or love vs. hate.

Think about the theme we call the circle of life. This epic concept explores birth, growth, degeneration, and death. Within that larger motif, we find opportunities to emphasize our subthemes.

For example, young vs. old is a common polarized theme with many opportunities for conflict. Both sides of this age-old conflict tend to be arrogant and sure of their position in each skirmish.

Wealth vs. poverty allows an author to delve into social issues and inequities. This polarity has great potential for conflict, which creates a deeper narrative.

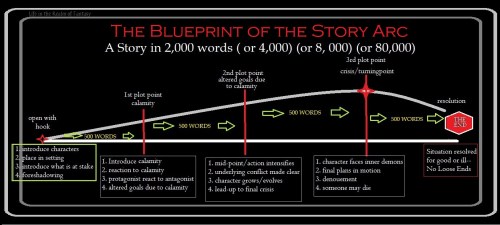

In my current outline, I seek to see beyond the obvious. I am searching for the smaller, more subtle contrasts to instill into my work. My intention is that these minor conflicts and hindrances will build toward each major plot point and support the central theme and add texture to the narrative.

This outline is evolving into a mystery. The main character is a peacekeeper who must solve it. To that end, I am inserting clues into the outline, guideposts for when I begin the first draft. On the line that details the plot arc for each chapter, some of those words will have antonym’s listed beside them, opportunities for roadblocks.

The theme of justice looms large in this novel. Hopefully, I can make this plot worthy of the characters I’ve created and who stand ready for NaNoWriMo.

Contrast is the fertile soil from which conflict grows. It can make protagonists more interesting, and in worldbuilding, it underscores the larger theme with less exposition.

Contrasts within the narrative shape the pacing of the action, as ease is contrasted against difficulty. In my projected piece, justice as a theme allows for many contrasts. Justice only exists because of injustice.

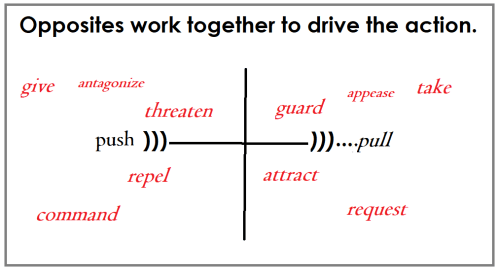

Polarity is a sneaky way for each word’s many nuances to raise or lower the tension in a scene.

Let’s look at the word cowardice. Cowardice is a gut reaction to fear. In real life, cowardice is often exhibited as a habitual evasion of the truth or as an avoidance mechanism.

It can be shown in an act as mild as a fib told for fear of hurting someone’s feelings. Or it can be as epic as an act of treason committed for fear of a political change in a direction the character finds untenable.

Bravery can be as small as a person facing a silly fear or as thrilling as a responder entering a burning building to rescue a victim.

I like stories with protagonists who contrast acts of bravery with small acts of cowardice. It adds texture to their otherwise perfect personalities and subtly powers their character arcs.

In all its many forms, polarity is a catalyst—the substance that enables a chemical reaction to proceed at a faster rate. In this case, the reactions we’re trying to speed up are the emotions of the reader.

I use the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms. This book is as essential to my writing as my copies of Damon Suede’s Activate and the Oxford Writer’s Thesaurus.

I use the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms. This book is as essential to my writing as my copies of Damon Suede’s Activate and the Oxford Writer’s Thesaurus.

Here is a sample of words found in the “D” section of the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms. I’ve posted this list of opposites before because they create powerful mental images:

- dangerous – safe

- dark – light

- decline – accept

- deep – shallow

- definite – indefinite

- demand – supply

- despair – hope

- discourage – encourage

- dreary – cheerful

- dull – bright, shiny

- dusk – dawn

In short, by employing polarities in our word selections, we add dimension and rhythm to our work. Polarity is an essential tool for both character creation and worldbuilding.

Often you can find great reference books second-hand, which will save you some cash. But even at full price, the books I referenced above are good investments.

However, we’re all cash-strapped these days, so a comprehensive list of common antonyms can be found at Enchanted Learning. Their website is a free resource.

Let’s have a look at how the Big 5 Publishers of literature did last year. You will note that the top players have changed since my last Big 5 article. Some of the big fish have been absorbed by the even bigger fish since we last looked at them.

Let’s have a look at how the Big 5 Publishers of literature did last year. You will note that the top players have changed since my last Big 5 article. Some of the big fish have been absorbed by the even bigger fish since we last looked at them.

For indies, our most reliable royalties have always come from digital sales, although we do sell some print books. But the best route to gaining loyal readers has been book fairs, conventions, and signings at bookstores.

For indies, our most reliable royalties have always come from digital sales, although we do sell some print books. But the best route to gaining loyal readers has been book fairs, conventions, and signings at bookstores. I am a planner, but I’m also a pantser. I’m just writing to a loose outline. All I need is a little free time in advance of November to let my mind wander.

I am a planner, but I’m also a pantser. I’m just writing to a loose outline. All I need is a little free time in advance of November to let my mind wander. Next, I ask the creative universe who the protagonist is. I create a brief personnel file, less than 100 words. It’s a paragraph with all the essential background information. Sometimes it takes a while to know what a character’s void is (a deep emotional wound), but it will emerge. I note the verbs, adjectives, and nouns the character embodies, as those give me all the necessary information.

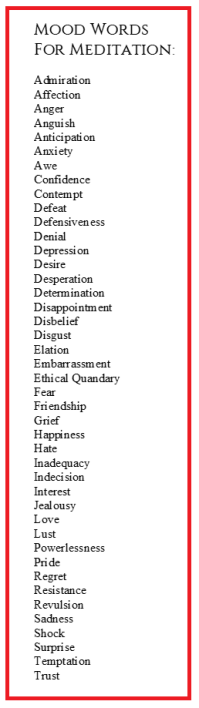

Next, I ask the creative universe who the protagonist is. I create a brief personnel file, less than 100 words. It’s a paragraph with all the essential background information. Sometimes it takes a while to know what a character’s void is (a deep emotional wound), but it will emerge. I note the verbs, adjectives, and nouns the character embodies, as those give me all the necessary information. Meditating on mood words often precipitates a flash of brilliance that has nothing to do with anything. What if …

Meditating on mood words often precipitates a flash of brilliance that has nothing to do with anything. What if … The second master class was on the how of creativity. Those of you who follow my blog know how the subject of creativity fascinates me. If you haven’t read any of Jeff Wheeler’s work, here is the link to my 2013 review of his first book, the

The second master class was on the how of creativity. Those of you who follow my blog know how the subject of creativity fascinates me. If you haven’t read any of Jeff Wheeler’s work, here is the link to my 2013 review of his first book, the  First, Lindsay pointed out that thinking is an action scene, as are conversations. He asked what a character does while thinking. He pointed out that Humphrey Bogart had a way of tugging on his ear when thinking, a habit that carried over into his movies. A side character with a certain amount of screen time but isn’t the POV character can be shown as real when they have a small personal habit that appears from time to time.

First, Lindsay pointed out that thinking is an action scene, as are conversations. He asked what a character does while thinking. He pointed out that Humphrey Bogart had a way of tugging on his ear when thinking, a habit that carried over into his movies. A side character with a certain amount of screen time but isn’t the POV character can be shown as real when they have a small personal habit that appears from time to time. When a character’s facial expressions take over the scene, they become cartoonish, two-dimensional displays of emotion with no substance. A landslide of microscopic showing can make your characters seem melodramatic. All that physical drama doesn’t show a character’s emotions. What is going on inside their heads?

When a character’s facial expressions take over the scene, they become cartoonish, two-dimensional displays of emotion with no substance. A landslide of microscopic showing can make your characters seem melodramatic. All that physical drama doesn’t show a character’s emotions. What is going on inside their heads? And this brings me to the core of this post. During NaNoWriMo, when I write new words as quickly as possible, I lean too heavily on the external, relying on a lot of smiling and shrugging. Conversations are action scenes, but too much “face time” is too much.

And this brings me to the core of this post. During NaNoWriMo, when I write new words as quickly as possible, I lean too heavily on the external, relying on a lot of smiling and shrugging. Conversations are action scenes, but too much “face time” is too much. In some circles, 40,000 words is a novel, but in fantasy, it is less than half a book.

In some circles, 40,000 words is a novel, but in fantasy, it is less than half a book. A detailed history of everyone’s background isn’t required. As a reader, all we need is a brief mention of historical information in conversation and delivered only when the protagonist needs to know it.

A detailed history of everyone’s background isn’t required. As a reader, all we need is a brief mention of historical information in conversation and delivered only when the protagonist needs to know it.

Rather than obsess about my lack of creativity, I decided to have fun with it. Several young writers in my NaNoWriMo region have said they used a plot generator to jumpstart their ideas, so I thought I’d give that a try.

Rather than obsess about my lack of creativity, I decided to have fun with it. Several young writers in my NaNoWriMo region have said they used a plot generator to jumpstart their ideas, so I thought I’d give that a try. Cursed

Cursed This plot generator has clearly been studying J.R.R. Tolkien, as it has managed to plagiarize the first paragraph of The Hobbit right down to the punctuation.

This plot generator has clearly been studying J.R.R. Tolkien, as it has managed to plagiarize the first paragraph of The Hobbit right down to the punctuation. When I write poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants, emotion words that begin with softer sounds.

When I write poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants, emotion words that begin with softer sounds. Concise writing is difficult for me because I love descriptors. So, I have to make my action words set the mood. To do that, I must use contrasts.

Concise writing is difficult for me because I love descriptors. So, I have to make my action words set the mood. To do that, I must use contrasts. The drive to understand why some books enthrall me and others leave me cold keeps me reading and looking for new stories.

The drive to understand why some books enthrall me and others leave me cold keeps me reading and looking for new stories. Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all.

Unfortunately, although we asked for a ground-floor condo, we were assigned a second-floor unit. My husband is managing the stairs – slowly. On the good side, we have the god’s-eye view of a wide stretch of beach, the perfect deck overlooking it all. Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose.

Writing is going as well as ever, a little up and down. I’m building the framework for a new story, which I will begin writing on November 1st. The world is already built; it’s an established world with many things that are canon and can’t be changed. So, I’m working my way through the bag of tricks that help me jar things loose. Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty.

Protagonist HER: Anna Lundquist, an unemployed game developer. She inherited an old farm and has moved there. She embarks on creating her own business designing anime-based computer games. Anna is shy, not good with men unless discussing books or computer games. VOID: Loss of family. VERBS: Create, Build, Seek, Defend, Fight, Nurture. Modifiers: Adaptable, ambitious, focused, independent, industrious, mature, nurturing, private, resourceful, responsible, simple, thrifty. Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

Antagonist HIM: Matt Gentry, owner of MGPopularGames and Anna’s former boss, is angry at Anna for leaving his firm. On a skiing trip with an old fraternity brother who owns an art supply store in Starfall Ridge, he sees her entering Nic’s coffeeshop. Matt discovers that Anna is now living in that town. He learns she has started her own company and is building an anime-based RPG. He goes back to Seattle and files an injunction to stop her, claiming that he owns the rights to her intellectual property. VOID: Narcissist. VERBS: Possess, Control, Desire, Covet, Steal, Lie, Torment.

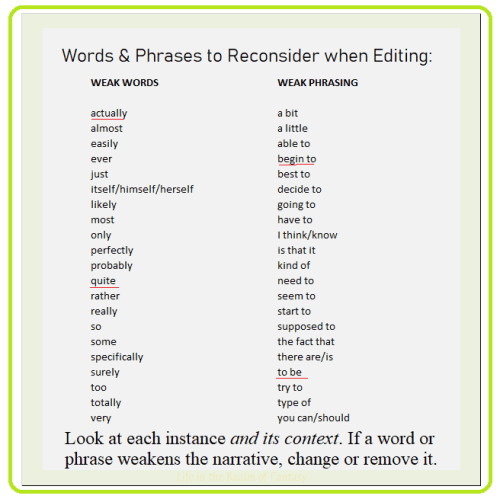

Today’s post focuses on word choice. What do you want to convey with your prose? This is where the choice and placement of words come into play. Active prose is constructed of nouns followed by verbs or verbs followed by nouns.

Today’s post focuses on word choice. What do you want to convey with your prose? This is where the choice and placement of words come into play. Active prose is constructed of nouns followed by verbs or verbs followed by nouns. The second draft revisions are where I do the real writing. It involves finetuning the plot arc, character arcs, and most importantly, adjusting phrasing.

The second draft revisions are where I do the real writing. It involves finetuning the plot arc, character arcs, and most importantly, adjusting phrasing. Some types of narratives should feel highly charged and action-packed. Most of your sentences should be constructed with the verbs forward if you write in genres such as sci-fi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers.

Some types of narratives should feel highly charged and action-packed. Most of your sentences should be constructed with the verbs forward if you write in genres such as sci-fi, political thrillers, and crime thrillers. What clues should you look for when trying to see why someone says you are too wordy?

What clues should you look for when trying to see why someone says you are too wordy?

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting style that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end.

Some authors are forceful in their style and throw you into the action. They have an in-your-face, hard-hitting style that comes on strong and doesn’t let up until the end. “I’m going to send you over. The chances are you’ll get off with life. That means you’ll be out again in twenty years. You’re an angel. I’ll wait for you.” He cleared his throat. “If they hang you I’ll always remember you.” [1]

“I’m going to send you over. The chances are you’ll get off with life. That means you’ll be out again in twenty years. You’re an angel. I’ll wait for you.” He cleared his throat. “If they hang you I’ll always remember you.” [1] But I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital.

But I prefer to keep my research in hardcopy form, rather than digital.  As we become confident in our writing, we learn more about grammar and punctuation in our native languages. We learn to write so others can understand us.

As we become confident in our writing, we learn more about grammar and punctuation in our native languages. We learn to write so others can understand us. However, quantifiers have a bad reputation because they can quickly become habitual, such as the word very.

However, quantifiers have a bad reputation because they can quickly become habitual, such as the word very. Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. Where we automatically place the words in the sentence is a recognizable fingerprint.

Our narrative voice comes across in our choice of hard or soft words and where we habitually position verbs in a sentence. Where we automatically place the words in the sentence is a recognizable fingerprint.