Words, carefully chosen and arranged with care, have the power to bring your writing to life.

We who write because we love words spend a great deal of time framing what our words say. We choose some words above others because they say what we mean more precisely, or they color our prose with the right emotion.

We who write because we love words spend a great deal of time framing what our words say. We choose some words above others because they say what we mean more precisely, or they color our prose with the right emotion.

We take our chosen words and bind them into small packets we call sentences. We take those sentences and build paragraphs, which become novels.

The author’s job is to understand how the grammar of their native language works. The great authors use those rules to energize their prose.

However, when it comes to word choices, some things are universal to the best work in all genres, from literary fiction and poetry to sci-fi and fantasy, to thrillers and cozy mysteries, or even Romance.

The world is in a state of flux—money is tight. In the US, the cost of getting a university education is prohibitive, with students incurring massive debt that follows them for years afterward. Some people have the luxury and the desire to seek a degree in writing.

Others must rely on self-education. To that end, here are seven rules professional writing programs teach about sentence and paragraph construction.

One: Verbs—we choose words with power. In English, words that begin with hard consonants sound tougher and carry more power.

Verbs are power words. Fluff words and obscure words used too freely are kryptonite, sapping the strength from our prose.

Two: Placement of verbs in the sentence can strengthen or weaken it.

Two: Placement of verbs in the sentence can strengthen or weaken it.

- Moving the verbs to the beginning of the sentence makes it stronger.

- Nouns followed by verbs make active prose.

I ran toward danger, never away.

Three: Parallel construction smooths awkward phrasing. When two or more ideas are compared in one sentence, each clause should use the same grammatical structure. They are parallel, and the reader isn’t jarred by them, absorbing what is said naturally.

What parallelism means can be shown by a quote attributed to Julius Caesar, who used the phrase “I came; I saw; I conquered” in a letter to the Roman Senate after he had achieved a quick victory in the Battle of Zela. Caesar gives equal importance to the different ideas of arriving, seeing, and conquering.

Four: Contrast—In literature, we use contrast to describe the difference(s) between two or more things in one sentence. The blue sun burned like fire, but the ever-present wind chilled me.

Four: Contrast—In literature, we use contrast to describe the difference(s) between two or more things in one sentence. The blue sun burned like fire, but the ever-present wind chilled me.

Five: Similes show the resemblances between two things through the use of words such as “like” and “as.” The blue sun burned like fire.

Similes differ from metaphors, which suggest something “is” something else. The pale moon shone, a lamp in the sky that comforted me.

Six: Deliberate repetition used occasionally emphasizes emotion and atmosphere but doesn’t increase wordiness.

- Repetition of the last word in a line or clause.

- Repetition of words at the start of clauses or verses.

- Repetition of words or phrases in the opposite sense.

- Repetition of words broken by some other words.

- Repetition of the same words at the end and start of a sentence.

- Repetition of a phrase or question to stress a point.

- Repetition of the same word at the end of each clause.

- Repetition of an idea, first in negative terms and then in positive terms.

- Repetition of words of the same root with different endings.

- Repetition at both the end and beginning of a sentence, paragraph, or scene.

- Repetition is a construction in poetry where the last word of one clause becomes the first word of the next clause.

“Every book is a quotation, and every house is a quotation out of all forests, and mines, and stone quarries; and every man is a quotation from all his ancestors.” Ralph Waldo Emerson, Prose and Poetry. [1]

Seven: Alliteration is the occurrence of the same letter (or sound) at the beginning of successive words, such as the familiar tongue-twister: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. Alliteration lends a poetic feeling to passages and enhances the atmosphere of a given scene without creating wordiness.

Seven: Alliteration is the occurrence of the same letter (or sound) at the beginning of successive words, such as the familiar tongue-twister: Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers. Alliteration lends a poetic feeling to passages and enhances the atmosphere of a given scene without creating wordiness.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary, (The Raven, by Edgar Allan Poe 1845) [2]

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees, (Birches, by Robert Frost 1916) [3]

The way we habitually construct our prose is our voice, and that voice determines the impact of our work. Different readers have widely different tastes, but no one enjoys bad writing.

Constructing our work to fit the market we are writing for is crucial to finding readers. However, all readers want to find good writing and are attracted to work that tells a story with atmosphere and emotion.

Active phrasing generates emotion. Sometimes, using similes, repetition, and alliteration in subtle applications enhances the worldbuilding without beating your reader over the head.

Active phrasing generates emotion. Sometimes, using similes, repetition, and alliteration in subtle applications enhances the worldbuilding without beating your reader over the head.

We all know worldbuilding must be organic and natural, but we don’t all know how to achieve it. Subtle application of these seven rules will empower your worldbuilding. The casual reader will be immersed but unaware of the mechanics. They won’t realize why the work is powerful.

Credits and Attributions:

[1] Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Complete Works. Published in 1904. Vol. VIII. Letters and Social Aims, VI. Quotation and Originality, Bartleby.com, accessed (June 11, 2022)

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “The Raven,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Raven&oldid=908701892 (accessed June 11, 2022).

[3] Wikipedia contributors, “Birches (poem),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Birches_(poem)&oldid=886359747 (accessed June 11, 2022).

Readers connect with these stories across generations and across the centuries because the fundamental concerns of human life aren’t unique to one society, one technological era, or one point in time.

Readers connect with these stories across generations and across the centuries because the fundamental concerns of human life aren’t unique to one society, one technological era, or one point in time. Acquiring food becomes their first priority. Having a surplus of food becomes a reason to celebrate. To go without adequate food for any length of time changes a person and makes one determined to never go hungry again.

Acquiring food becomes their first priority. Having a surplus of food becomes a reason to celebrate. To go without adequate food for any length of time changes a person and makes one determined to never go hungry again. Love and loss, safety and danger, loyalty and betrayal—the eternal themes of tragedy and resolution. Hardship contrasted against ease provides the story with texture, turning a wall of “bland” into something worth reading.

Love and loss, safety and danger, loyalty and betrayal—the eternal themes of tragedy and resolution. Hardship contrasted against ease provides the story with texture, turning a wall of “bland” into something worth reading. We writers must make our words count. We have to show the comfort zone in the moments leading up to the disaster, not too much, but just enough to show what will soon be lost.

We writers must make our words count. We have to show the comfort zone in the moments leading up to the disaster, not too much, but just enough to show what will soon be lost. Scenes of conflict are crucial to the advancement of the story. They should be inserted into the novel as if one were staging a pivotal scene in a film.

Scenes of conflict are crucial to the advancement of the story. They should be inserted into the novel as if one were staging a pivotal scene in a film. If you have no experience with combat or fighting, you don’t understand the limits of a normal athlete’s physical abilities. So, you must do the research. Think of how the human body works in reality. If your character knees a foe in the jaw, how is it possible?

If you have no experience with combat or fighting, you don’t understand the limits of a normal athlete’s physical abilities. So, you must do the research. Think of how the human body works in reality. If your character knees a foe in the jaw, how is it possible? If you don’t show how such a strange hit could happen, the reader will say, “That’s impossible.” It’s a risky choice though, because going into that kind of detail bores the heck out of our readers. Our readers mind will fill in the details and if it’s confusing, they may stop reading.

If you don’t show how such a strange hit could happen, the reader will say, “That’s impossible.” It’s a risky choice though, because going into that kind of detail bores the heck out of our readers. Our readers mind will fill in the details and if it’s confusing, they may stop reading. Don’t do this for every incident. After they are armed and armored as much as they are going to be the first time, just have them meet the enemy, skirmish, and continue on. The reader already knows what armor and weapons they had.

Don’t do this for every incident. After they are armed and armored as much as they are going to be the first time, just have them meet the enemy, skirmish, and continue on. The reader already knows what armor and weapons they had. In real life, conflict happens on a sliding scale. It begins with a disagreement and escalates to an all-out war. While my outline will have a note alerting me to the level of conflict that must happen, I choreograph my fights to reflect that sliding level of intensity.

In real life, conflict happens on a sliding scale. It begins with a disagreement and escalates to an all-out war. While my outline will have a note alerting me to the level of conflict that must happen, I choreograph my fights to reflect that sliding level of intensity. Person-to-person combat doesn’t stretch for hours because no matter how well trained a fighter is, no one has that kind of strength.

Person-to-person combat doesn’t stretch for hours because no matter how well trained a fighter is, no one has that kind of strength. A typical

A typical  I try to show this discreetly by sitting back and visualizing the scene after the choreography is laid on paper. I replay it in my mind as if I were a witness to the events and look for each combatant’s facial expressions and reactions.

I try to show this discreetly by sitting back and visualizing the scene after the choreography is laid on paper. I replay it in my mind as if I were a witness to the events and look for each combatant’s facial expressions and reactions.

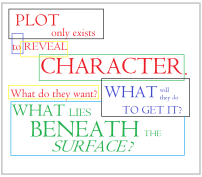

The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

The first incident has a domino effect. More events occur, pushing the protagonist out of his comfortable life and into danger. Fear of death, fear of loss, fear of financial disaster, fear of losing a loved one—terror is subjective and deeply personal.

However, the reader has an edge—they will be offered clues from the antagonists’ side, which the characters don’t know. The antagonist’s actions will affect the plot in the future. Even if the antagonist isn’t an overt enemy at the outset, the readers’ knowledge creates a sense of unease, a subliminal worry that things will go wrong.

However, the reader has an edge—they will be offered clues from the antagonists’ side, which the characters don’t know. The antagonist’s actions will affect the plot in the future. Even if the antagonist isn’t an overt enemy at the outset, the readers’ knowledge creates a sense of unease, a subliminal worry that things will go wrong. But not every author has that option.

But not every author has that option. In most standard book contracts, royalty terms for authors are terrible, and this is especially true for eBook sales. Most eBooks are sold through online retailers like Amazon. If you’re a traditionally published author and your publisher priced your eBook at $9.99, this is how the Amazon numbers break out. No matter what you think of Amazon, it is still the Big Fish in the Publishing and Bookselling Pond:

In most standard book contracts, royalty terms for authors are terrible, and this is especially true for eBook sales. Most eBooks are sold through online retailers like Amazon. If you’re a traditionally published author and your publisher priced your eBook at $9.99, this is how the Amazon numbers break out. No matter what you think of Amazon, it is still the Big Fish in the Publishing and Bookselling Pond: However, to be considered for a traditional contract, you should hire an editor, beta reader, and proofreader to ensure the manuscript you submit to an agent or editor demonstrates your ability to turn out a good, professional product.

However, to be considered for a traditional contract, you should hire an editor, beta reader, and proofreader to ensure the manuscript you submit to an agent or editor demonstrates your ability to turn out a good, professional product. Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills.

Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills. Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with  The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated.

The plan or design is submitted to the client, who likes it. A mockup of the first iteration is submitted to the client, who still likes it, but … their needs have changed a little, and a new adjustment must be incorporated. Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books.

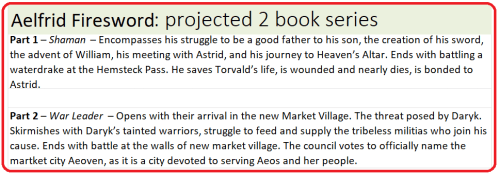

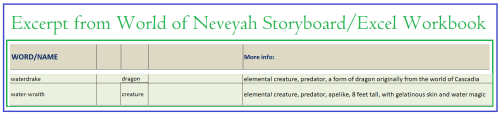

Books are one area where project creep is not only appreciated but encouraged. Stories are particularly prone to this continual expansion of the original ideas. Short stories grow into novellas and then into novels, becoming a series of books. The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play.

The first aspect of this is to Identify your Project Goals – create a rudimentary outline with names, who they are in relation to the protagonist, and decide who is telling the story. Remember, your story is your invention. Some inventions are in development for years before they get to market. Others are complete and ready to market in a relatively short time. Regardless of your production timeline, this is where project management skills really come into play. Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions.

Your map doesn’t have to be fancy – all you need are some lines and scribbles telling you all the essential things, like which direction is north and what certain towns are named. Use a pencil, to easily update your map if something changes during revisions. Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task.

Time can get a little mushy when we are winging it through a manuscript. A calendar gives us a realistic view of how long it takes to travel from point A to point B, or how much time it will take to complete a task. Thus, it makes sense to consider whether your story is complex enough to hold up well across a series.

Thus, it makes sense to consider whether your story is complex enough to hold up well across a series. If you are done with your first draft and are just now realizing your novel could be the beginning of a saga, you should consider making notes as to what the future holds for your crew beyond the end. Otherwise, you may find yourself writing a continuation of book one, but with no goal, no purpose.

If you are done with your first draft and are just now realizing your novel could be the beginning of a saga, you should consider making notes as to what the future holds for your crew beyond the end. Otherwise, you may find yourself writing a continuation of book one, but with no goal, no purpose. So, for a saga you might want to draw up an overall story arc for the entire series. For a standalone book featuring a recurring character, you likely won’t need to have an all-encompassing projected arc.

So, for a saga you might want to draw up an overall story arc for the entire series. For a standalone book featuring a recurring character, you likely won’t need to have an all-encompassing projected arc. Think about it – the universe contains all we can measure and know, all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all forms of matter and energy. It likes balls and spirals and has a structure that repeats itself. This is reflected in the shape and behavior of the smallest particles to the largest quasars.

Think about it – the universe contains all we can measure and know, all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all forms of matter and energy. It likes balls and spirals and has a structure that repeats itself. This is reflected in the shape and behavior of the smallest particles to the largest quasars. First off, no matter our conscious thoughts regarding the universe and God, writers don’t exist in reality. We exist in what we think reality is, and collectively, we create it as we go along, for good or ill.

First off, no matter our conscious thoughts regarding the universe and God, writers don’t exist in reality. We exist in what we think reality is, and collectively, we create it as we go along, for good or ill. But if you make a map of what you can see, your own

But if you make a map of what you can see, your own  As I wrote, the outline for that first book took its shape. The written universe is in constant flux, and the storyboard records the changes and keeps the fabric of time from warping.

As I wrote, the outline for that first book took its shape. The written universe is in constant flux, and the storyboard records the changes and keeps the fabric of time from warping. Once I have decided the proposed length, I know where the turning points are and what should happen at each. The outline ensures an arc to both the overall story and the characters’ personal growth.

Once I have decided the proposed length, I know where the turning points are and what should happen at each. The outline ensures an arc to both the overall story and the characters’ personal growth.

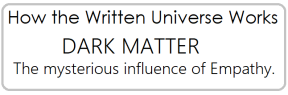

In other words, something we can’t see or measure is out there, shaping our known universe. For lack of a better term, scientists refer to it as “dark matter” and “dark energy.”

In other words, something we can’t see or measure is out there, shaping our known universe. For lack of a better term, scientists refer to it as “dark matter” and “dark energy.” Unless your story is set in a school (such as the

Unless your story is set in a school (such as the  In real life, if a person had the kind of power that our fictional empaths wield, we would hope they were noble, compassionate, and above all, respectful of other people’s wish for privacy. One would want them to be circumspect and never rummage in people’s minds uninvited.

In real life, if a person had the kind of power that our fictional empaths wield, we would hope they were noble, compassionate, and above all, respectful of other people’s wish for privacy. One would want them to be circumspect and never rummage in people’s minds uninvited. What does healing cost the healer? Does it exhaust them? Does some of the healing magic come from the patient? Do they need to sleep afterward?

What does healing cost the healer? Does it exhaust them? Does some of the healing magic come from the patient? Do they need to sleep afterward?