We all use the same words to tell the same stories.

Why do I say such a terrible thing? It’s true. All stories are derived from a few basic plots, and we have only so many words in the English language with which to tell them.

Why do I say such a terrible thing? It’s true. All stories are derived from a few basic plots, and we have only so many words in the English language with which to tell them.

Plot Archetypes as defined by Christopher Booker in his work, The Seven Basic Plots:

Overcoming the monster

Overcoming the monster- The quest

- Voyage and return

- Comedy

- Tragedy

- Rebirth

- The Rule of Three

The words we habitually use to show a scene will be recognizable as our voice. I know a lot of words and their alternatives, and I try to learn new ones every day. But I often find myself stuck when pounding out a first draft, using a particular word over and over. My brain knows what I’m trying to say but can’t be too creative.

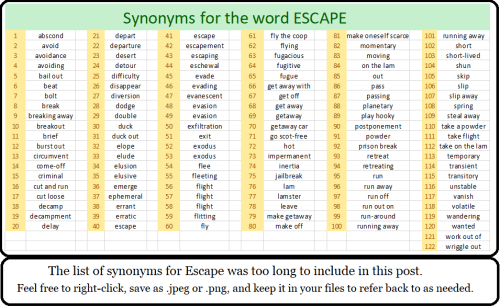

Fortunately, this sin is noticeable when I get to revisions, and that is when I hunt down the synonyms, alternative words that mean the same thing.

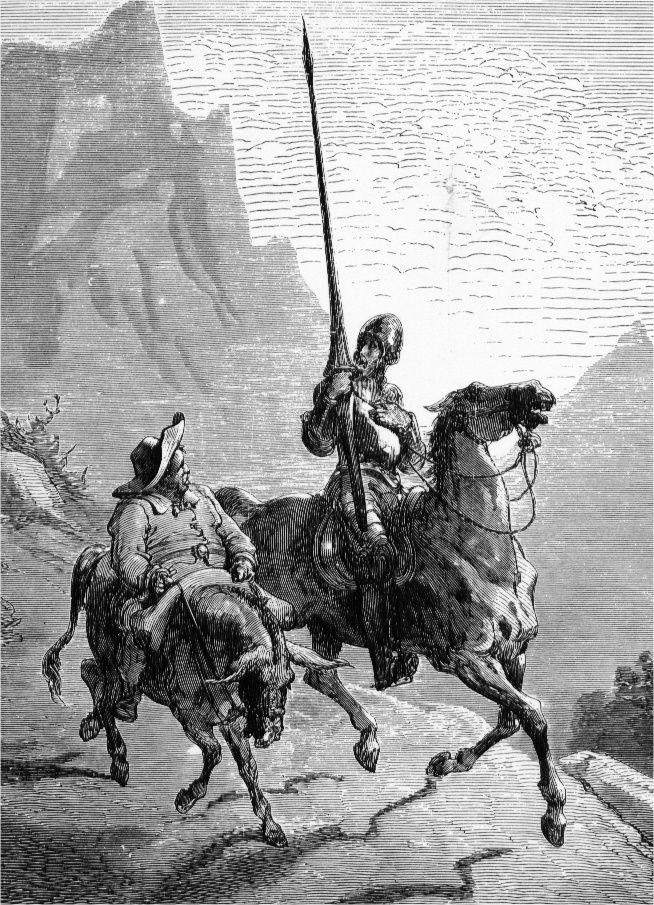

Words with only a small number of alternatives become problems for me. This happens in my work with the word sword. The other options for the word sword are many. Unfortunately, most describe a specific type of weapon – epee, rapier, cutlass, saber/sabre, etc.

Unfortunately, my swords are only broadswords or claymores. Thus, I am limited to sword, blade, weapon … you get the drift. The lack of alternatives does one good thing, though – it keeps me from indulging in long, drawn-out fight scenes.

Other words cause problems too. Sometimes, the thesaurus available in my word-processing program doesn’t offer me enough substitutes to make a good choice.

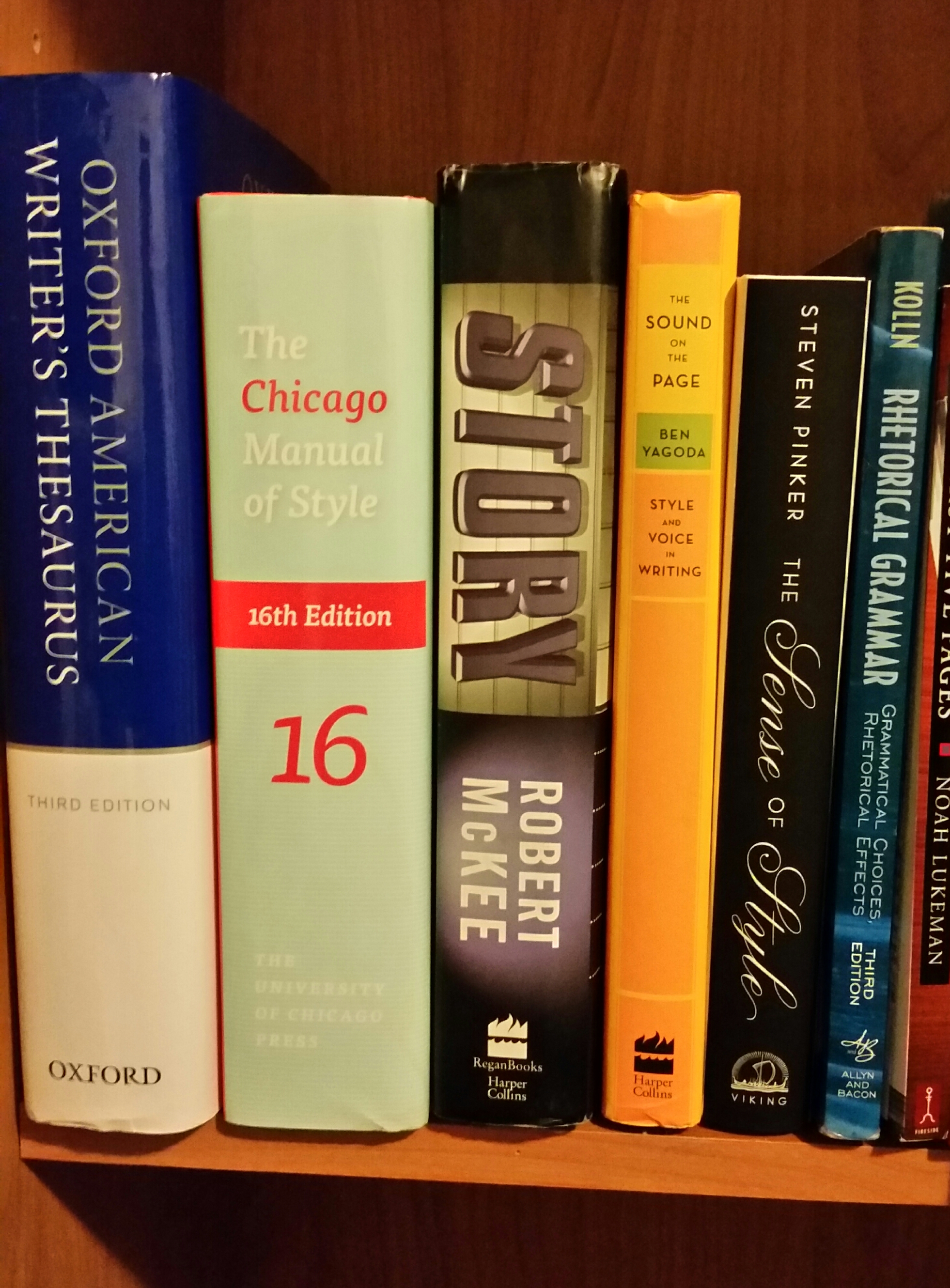

For that reason, I have the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms and Oxford American Writers’ Thesaurus near to hand. I also have a book called Activate, written by Damon Suede, a thesaurus of verbs, actions, and tactics. I refer to these books when I must search for an alternative to a word I am leaning too heavily on.

For that reason, I have the Oxford Dictionary of Synonyms and Antonyms and Oxford American Writers’ Thesaurus near to hand. I also have a book called Activate, written by Damon Suede, a thesaurus of verbs, actions, and tactics. I refer to these books when I must search for an alternative to a word I am leaning too heavily on.

Which happens far too often.

Memory is a mushy thing. I prefer a hard copy reference book rather than the internet, as I remember what I read on paper better than what I read on screen. However, the internet is a perfectly reasonable cost-free alternative. I get sidetracked too easily when doing research on the net. Hard copies of reference books encourage me to do the research and get back to work.

So, we know that we all tell stories with fundamentally similar plots, and we all must use words with the same meanings.

But we sound different on the page. Why is this?

The way we habitually write prose is our unique voice. The word I select might mean the same as the one you use, but I might choose a different form.

When we write, we build a specific image for our readers. We select words intentionally for their nuances (distinctions, subtleties, shades, refinements, etc.).

We use words that convey our vision of the mood, atmosphere, and information. You and I may be writing the same plot, but my vision of it is different from yours.

Let’s write a story about a hero who finds a magical object and an evil entity who wants possession of it.

J.R.R. Tolkien may have used that plot in the Lord of the Rings, but what we write will be ours, not his. Your words will show the hero in a setting and communicate an atmosphere completely different from what my words express.

How do our word choices add depth to world-building? An example might be sound or color. How do you show an intense sound or color? Loud is a word that works for both sound and color.

Thunderous conveys more power than loud, even though they mean the same thing in the context of sound.

Lurid conveys more power than loud, and in the context of color, they mean the same thing.

Let’s look more closely at the word loud:

Noisy

Noisy- Boisterous

- Deafening

- Raucous

- Lurid

- Flamboyant

- Ostentatious

- Thunderous

- Strident

- Vulgar

- Loudmouthed

These are only a few of the many options we have to work with. The website www.PowerThesaurus.com lists 1,992 alternatives for the word loud.

How about the word “disruptive”? It’s a straightforward, blunt adjective. Maybe you don’t want to say it bluntly. Would you choose the word obstreperous or the more common form, argumentative? They mean the same thing, but both begin with a vowel and feel passive.

Hostile, confrontational, surly—many common words convey the information that a person is being difficult in a simple but powerful way. The synonyms for disruptive express many different shades of meaning and might be more appropriate to your narrative.

Use your vocabulary but don’t get too creative. Do your readers a favor and use words that most people won’t need a dictionary to understand.

I don’t mean to say that rarely used words should be ignored. Our prose should never be “dumbed-down,” but we shouldn’t use big words just to show how literate we are.

My Texan editor refers to those convoluted morsels of madness as “ten-dollar words.” A ten-dollar word is a long obscure word used in place of one that is smaller and more well-known. This is why I probably wouldn’t use obstreperous in place of disruptive, but I might choose rebellious or confrontational.

My Texan editor refers to those convoluted morsels of madness as “ten-dollar words.” A ten-dollar word is a long obscure word used in place of one that is smaller and more well-known. This is why I probably wouldn’t use obstreperous in place of disruptive, but I might choose rebellious or confrontational.

The problem is, sometimes, I can’t find the right words to show what I envision. I can see it but can’t express it. It annoys me to leave that scene and come back to it later.

Other times I have all the words I need, and those are the best days, the days I am glad to be a writer.

We imagine and assemble stories for other people’s entertainment. We paint those images with words carefully chosen to draw the most precise framework for the reader to hang their imagination on.

The real story happens inside the reader’s head.

The words we choose make the reader’s experience richer or poorer. As a reader, I live for those books written by authors who are bold when they choose their words.

Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

Even if you have an MFA degree, you could spend a lifetime learning the craft and never learn all there is to know about the subject. We join writing groups, buy books, and most importantly, read. We analyze what we have read and figure out what we liked or disliked about it. Then, we try to apply what we learned to our work.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos.

You have just spent the last year or more combing through your novel. This is another example of silly advice that doesn’t consider how complex and involved the process of getting a book written and published is. I love writing, but when you have been working on a story through five drafts, it can be hard to get excited about making one more trip through it, looking for typos. When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides.

When we first embark on learning this craft, we latch onto handy, easy-to-remember mantras because we want to educate ourselves. Unless we’re fortunate enough to have a formal education in the art of writing, we who are just beginning must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides. We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often.

We can easily bludgeon our work to death in our effort to fit our square work into round holes. In the process of trying to obey all the rules, every bit of creativity is shaved off the corners. A great story with immense possibilities becomes boring and difficult to read. As an avid reader and reviewer, I see this all too often. However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.

However, (cue the danger theme music), once I have set it aside for a while, I will have to begin the revision process. That is when writing becomes work. This is the moment I discover the child of my heart isn’t perfect – my action scenes are a little … confusing.

What motivated the action?

What motivated the action?

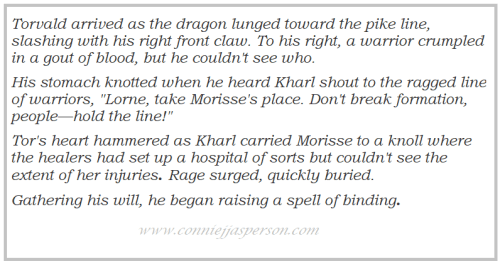

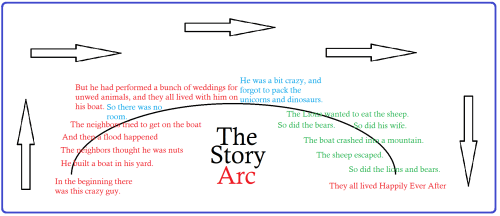

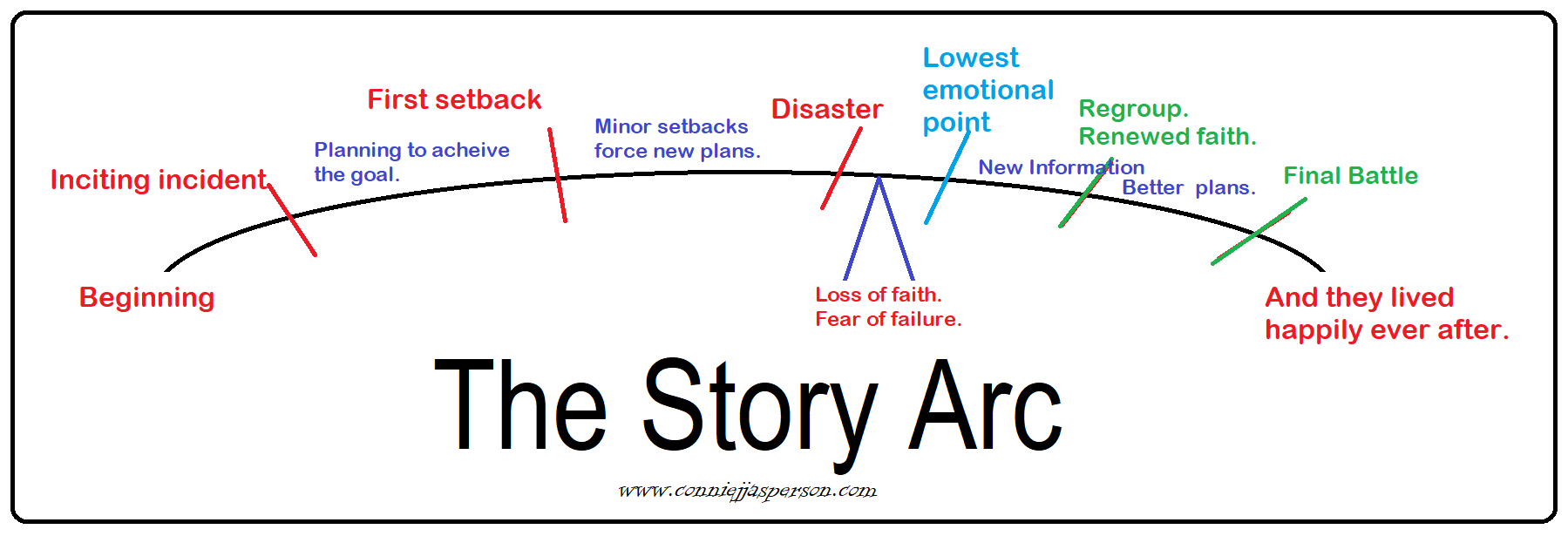

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages.

We add the details when we begin the revision process. One of the elements we look for in our narrative is pacing, or how the story flows from the opening scene to the final pages. This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

This string of scenes is like the ocean. It has a kind of rhythm, a wave action we call pacing. Pacing is created by the way an author links actions and events, stitching them together with quieter scenes: transitions.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Internal monologues should humanize our characters and show them as clueless about their flaws and strengths. It should even show they are ignorant of their deepest fears and don’t know how to achieve their goals. With that said, we must avoid “head-hopping.” The best way to avoid confusion is to give a new chapter to each point-of-view character. Head-hopping occurs when an author describes the thoughts of two point-of-view characters within a single scene.

Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills.

Regardless of your publishing path, you must budget for certain things. You can’t expect your royalties to pay for them early in your career – and many award-winning authors must still work at their day jobs to pay their bills. Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Conferences are an extension of the self-education process. I have discovered so much about the craft of writing, the genres I write in, and the publishing industry as a whole—things I could only learn from other authors. I gained an extended professional network by joining

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with

Sometimes I am invited to participate in panels or offer a workshop, and I can share my experiences with others. Either way, I learn things. In September, I will be on a panel with  Time interests me because I mostly write fantasy, although I write contemporary short fiction and poetry. Fantasy, and all speculative fiction, relies heavily on worldbuilding, and managing time is a facet of that skill.

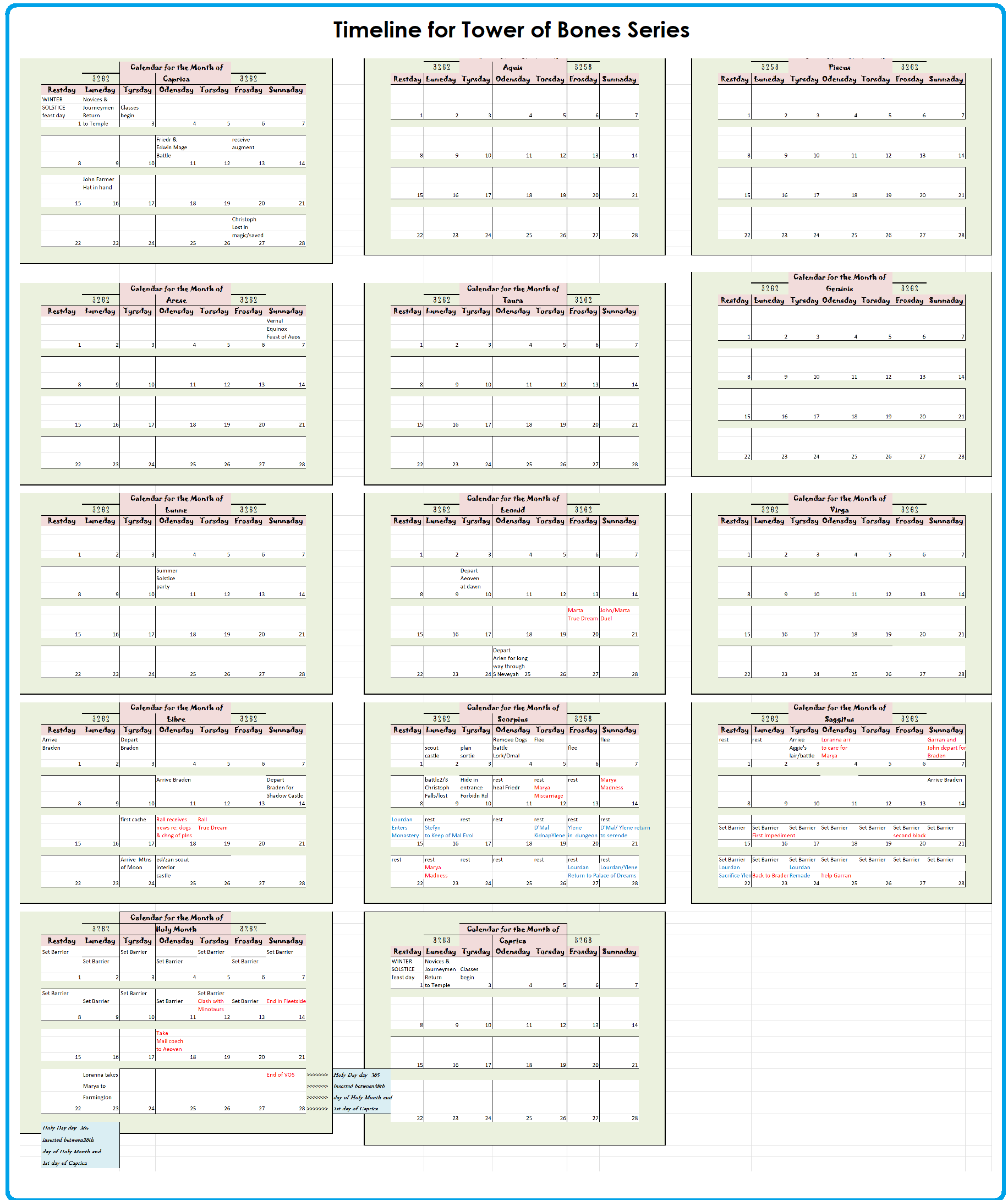

Time interests me because I mostly write fantasy, although I write contemporary short fiction and poetry. Fantasy, and all speculative fiction, relies heavily on worldbuilding, and managing time is a facet of that skill. HERE is where I confess my great regret: in 2008, a lunar calendar seemed like a good thing while creating my first world.

HERE is where I confess my great regret: in 2008, a lunar calendar seemed like a good thing while creating my first world. In an even worse bout of predictability, I went with the names we currently use when I named the days, only I twisted them a bit and gave them the actual Norse god’s name. (The gods and goddesses of Neveyah are not Norse.)

In an even worse bout of predictability, I went with the names we currently use when I named the days, only I twisted them a bit and gave them the actual Norse god’s name. (The gods and goddesses of Neveyah are not Norse.) I LEARNED from my mistakes – the timeline for the Billy’s Revenge 3-book series, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland, uses the familiar calendar we use today.

I LEARNED from my mistakes – the timeline for the Billy’s Revenge 3-book series, Huw the Bard, Billy Ninefingers, and Julian Lackland, uses the familiar calendar we use today. However, we can learn a great deal from books embodying poorly executed plots and badly scripted dialogue.

However, we can learn a great deal from books embodying poorly executed plots and badly scripted dialogue. The first books of the series establish a science of magic. One can either use chaotic magic or ordered magic. Although some mages can only use one side or the other, the most powerful mages can manipulate both sides of the magic. The entire series explores this concept well. It is a well-planned magic system, with good rules.

The first books of the series establish a science of magic. One can either use chaotic magic or ordered magic. Although some mages can only use one side or the other, the most powerful mages can manipulate both sides of the magic. The entire series explores this concept well. It is a well-planned magic system, with good rules. Structurally, the books in this subseries feel like he knew how to end it but struggled to fill in the arc. Past events and conversations get repeated verbatim to every new character. Long passages of remembering and agonizing over what is done and dusted fluffs up the narrative.

Structurally, the books in this subseries feel like he knew how to end it but struggled to fill in the arc. Past events and conversations get repeated verbatim to every new character. Long passages of remembering and agonizing over what is done and dusted fluffs up the narrative. To me, book 21 reads as if (while books 19 and 20 were in the publishing gauntlet) he still had to fluff up the ending to make book 21 long enough to be considered a novel. The evidence of a lack of genuine inspiration is the absurd “scar” the protagonist is left with after winning an unbelievable victory and nearly dying.

To me, book 21 reads as if (while books 19 and 20 were in the publishing gauntlet) he still had to fluff up the ending to make book 21 long enough to be considered a novel. The evidence of a lack of genuine inspiration is the absurd “scar” the protagonist is left with after winning an unbelievable victory and nearly dying. Everyone, even your favorite author, writes a stinker now and then.

Everyone, even your favorite author, writes a stinker now and then.  When I am finished with the revisions, I will format my manuscript as both ebooks and paper books. At that point, I will be looking for proofreaders.

When I am finished with the revisions, I will format my manuscript as both ebooks and paper books. At that point, I will be looking for proofreaders. If you didn’t see it when I mentioned it above, I will repeat it: proofreading is not editing. We discussed self-editing in my previous post,

If you didn’t see it when I mentioned it above, I will repeat it: proofreading is not editing. We discussed self-editing in my previous post, Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These happen when making revisions, even by the most meticulous of authors. The editor won’t see any mistakes you introduce after they have completed their work on the manuscript.

Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These happen when making revisions, even by the most meticulous of authors. The editor won’t see any mistakes you introduce after they have completed their work on the manuscript. Unfortunately, my last book went live when I thought I was ordering a pre-publication proof.

Unfortunately, my last book went live when I thought I was ordering a pre-publication proof. Our stories take the reader to exotic places and introduce them to other realities. When we publish a book, we hope it will find a reader on the day they were looking for just such an escape.

Our stories take the reader to exotic places and introduce them to other realities. When we publish a book, we hope it will find a reader on the day they were looking for just such an escape. I wrote poetry and lyrics for a heavy metal band when I first started out. I was young, sincere, and convinced I had to impart a message with every word. I didn’t know until twenty years later when I came across my old notebook that my poems weren’t honest. Eighteen-year-old me was trying to make a point rather than offering ideas for further thought.

I wrote poetry and lyrics for a heavy metal band when I first started out. I was young, sincere, and convinced I had to impart a message with every word. I didn’t know until twenty years later when I came across my old notebook that my poems weren’t honest. Eighteen-year-old me was trying to make a point rather than offering ideas for further thought. Children are unimpressed by the fact their parents might write a story or play music or paint or do any of the creative arts.

Children are unimpressed by the fact their parents might write a story or play music or paint or do any of the creative arts. As Ursula K. LeGuin said in her excellent book,

As Ursula K. LeGuin said in her excellent book,  day, should we so desire. Reading is how we come to understand writing and the art of story. Mr. King also admonishes us to learn the fundamentals of punctuation and grammar.

day, should we so desire. Reading is how we come to understand writing and the art of story. Mr. King also admonishes us to learn the fundamentals of punctuation and grammar. Every editor will tell you no amount of money is worth the time and effort it would take to teach an author how to write coherent, readable prose. That is what seminars, books on craft, and books on style and grammar are for.

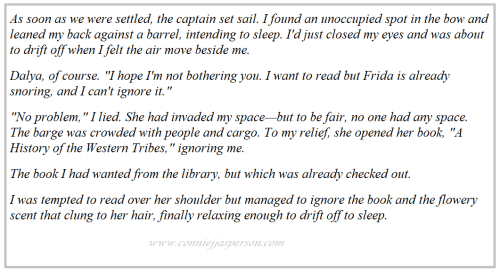

Every editor will tell you no amount of money is worth the time and effort it would take to teach an author how to write coherent, readable prose. That is what seminars, books on craft, and books on style and grammar are for. I want to read an honest story about people who seem real, who have the kind of problems we can all relate to on a human level. I want to read a story that comes from an author’s deepest soul. The setting doesn’t matter—it can be set on Mars or in Africa. Characters matter, and their story matters.

I want to read an honest story about people who seem real, who have the kind of problems we can all relate to on a human level. I want to read a story that comes from an author’s deepest soul. The setting doesn’t matter—it can be set on Mars or in Africa. Characters matter, and their story matters. We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names.

We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names. The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous.

The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous.