I love novels that become series. I think this is because I hate to see the story end, or maybe I wonder how the whole thing started. Most of the time, when an author first writes a novel, they don’t consider that it may end up with a sequel or two. (Or 30). Many cozy mystery and sci-fi fantasy series begin this way.

Sometimes, a first novel is well-received, with engaging characters and a plot arc that moves along to a satisfying conclusion. People want more, and so the series begins.

Sometimes, a first novel is well-received, with engaging characters and a plot arc that moves along to a satisfying conclusion. People want more, and so the series begins.

But then, there are authors who know at the outset that one book won’t tell the story. They build a plot outline around two or more novels.

Even if you plan a series at the outset, the novel that opens the series must have a complete story arc, a finite, satisfying ending, and be able to stand alone. I say this because it takes time to write a novel. Readers nowadays are impatient and are vocal about it on social media, with a tendency to heap criticism on the offending author.

A projected series is a universe unto itself, even if it is set in the real world. It is the story of that universe, told over the course of several books.

Speaking as a reader, if you are writing a series, you must plan the overall structure well in advance. Every book in the series needs to have its own plot and must end at a place that doesn’t leave the reader wondering what the hell just happened.

There are two kinds of series, episodic and continuing, or as I like to think of them, finite and infinite.

The episodic series is like a television series. Each novel has a new adventure for a previously established set of characters. In some ways, these are easiest to write, especially when each book features established characters in an established world. (Sorry about the repetition there.) Many cozy mysteries and fantasy series are episodic. They are an infinite series of standalone stories.

The episodic series is like a television series. Each novel has a new adventure for a previously established set of characters. In some ways, these are easiest to write, especially when each book features established characters in an established world. (Sorry about the repetition there.) Many cozy mysteries and fantasy series are episodic. They are an infinite series of standalone stories.

Some episodic series follow a particular group of characters, but others might feature a different protagonist. They are all set in a specific world, whether they follow one protagonist or several. The installments often jump around in that universe’s historical timeline. Think Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series or L.E. Modesitt Jr.’s Recluce series.

The continuing series requires some advance planning. It is a finite multi-volume series of books covering one group’s efforts to achieve a single epic goal. While each book may be set in an established world, it might feature an entirely different set of characters and their storyline.

The story usually has a strong theme that unites the series. It might be a theme such as the hero’s journey or young people coming of age. Or it might follow the life of one main character and their sidekicks as they struggle to complete an arduous quest. Robert Jordan’s (and Brandon Sanderson’s) The Wheel of Time series is a prime example of the continuing series.

The story usually has a strong theme that unites the series. It might be a theme such as the hero’s journey or young people coming of age. Or it might follow the life of one main character and their sidekicks as they struggle to complete an arduous quest. Robert Jordan’s (and Brandon Sanderson’s) The Wheel of Time series is a prime example of the continuing series.

An episodic series is easier to plan as each one is a single novel. There are no loose ends, so if the author stops writing in that series, nothing is left hanging.

A continuing series must have a complete plot arc for each book. Each novel is only a section or chapter of the larger story. Speaking as a reader, please keep track of the subplots via an outline. I say this so you don’t leave loose ends but also to ensure the subplots come together at the final battle.

Sequels happen when an author is in love with their characters, and those characters and their stories resonate with readers. Sequels are how trilogies become series.

Companion novels occur simultaneously alongside the main story but feature side characters doing their own thing.

Prequels are one of my favorite kinds of novels. I am always curious as to how the whole thing started.

Prequels are one of my favorite kinds of novels. I am always curious as to how the whole thing started.

Spin-offs might feature side characters or the protagonist’s descendants.

So, how do we manage the character arc for one group over the course of a series? I suggest storyboarding. Write a synopsis of what you think the Big Picture is, the entire story. Write it out even if that synopsis goes for 5,000 to 10,000 words.

If that storyboard looks too large for one book, separate the sections into however many novels of reasonable length it will take.

An outline will help you decide on your structure. You’ll have a better idea of how each plot will unfold.

Once you have figured out the entire arc of the series, make an outline of book one. This allows your creative mind to insert foreshadowing. This will happen via the clues and literary easter eggs that surface as the series goes on.

Once you have figured out the entire arc of the series, make an outline of book one. This allows your creative mind to insert foreshadowing. This will happen via the clues and literary easter eggs that surface as the series goes on.

I suggest waiting to outline the next book until after book one is finished and ready for the final edit. Plots constantly evolve as we write. Book one is the foundation novel of the series, so it must be completed before you begin building the rest of the story.

Maps and calendars are essential tools for the author, no matter what genre you are writing in. Regardless of how you create your stylesheet/storyboard, I suggest you include these elements:

An OUTLINE of events including a prospective ending. Update it as things evolve.

A GLOSSARY is especially important. I suggest you keep a list of names and invented words as they arise, all spelled the way you want them.

MAPS are good but don’t have to be fancy. All you need is something rudimentary to show you the layout of the world.

A CALENDAR of events is especially important.

Outlining the next novel should be simpler if you kept a record of all the changes that evolved to your original outline. The stylesheet/storyboard is a good tool for fantasy authors because we invent entire worlds, religions, and magic systems. We don’t want to contradict ourselves or have our characters’ names change halfway through the book—with no explanation.

Next week, we will look at creating a calendar for stories set in a speculative fiction world. We will look at some of my failures and see why simpler is usually better.

Next week, we will look at creating a calendar for stories set in a speculative fiction world. We will look at some of my failures and see why simpler is usually better.

Technically, I am a full-time writer. For about ten years after I retired from corporate America, I had regular office hours for writing. Nothing lasts forever, and now I am drawing on the habits I developed during my years as a hobbyist. I write when I can and devote the rest of my time to caring for my family.

Technically, I am a full-time writer. For about ten years after I retired from corporate America, I had regular office hours for writing. Nothing lasts forever, and now I am drawing on the habits I developed during my years as a hobbyist. I write when I can and devote the rest of my time to caring for my family. So, let’s talk a little more about what we write. Most of us don’t intentionally write to preach to people, but the philosophies we hold dear do come out.

So, let’s talk a little more about what we write. Most of us don’t intentionally write to preach to people, but the philosophies we hold dear do come out.

We each grow and develop in a way that is unique to us. Sometimes, we are hardened by our life experiences, and our protagonists have that jaded sensibility. Other times, we accept our own human frailties, and our protagonists are more forgiving.

We each grow and develop in a way that is unique to us. Sometimes, we are hardened by our life experiences, and our protagonists have that jaded sensibility. Other times, we accept our own human frailties, and our protagonists are more forgiving. The battles we fight on the home front don’t have to be serious all the time. Sometimes, they can be hilarious. When your spouse has Parkinson’s, life is like a

The battles we fight on the home front don’t have to be serious all the time. Sometimes, they can be hilarious. When your spouse has Parkinson’s, life is like a  Suddenly, some joker turns the blender on, and everything goes to hell. They turn it off, and you think, “Okay, disaster averted. It’s gonna be okay.”

Suddenly, some joker turns the blender on, and everything goes to hell. They turn it off, and you think, “Okay, disaster averted. It’s gonna be okay.” Life is like a blended margarita. It’s all in how you look at it, so stay cool and enjoy the party for as long as it lasts.

Life is like a blended margarita. It’s all in how you look at it, so stay cool and enjoy the party for as long as it lasts. Artist: Carl Julius von Leypold (1806–1874)

Artist: Carl Julius von Leypold (1806–1874) The more frequently you write, the more confident you become. Spending a small amount of time writing every day is crucial. It develops discipline, and personal discipline is essential if you want to finish a writing project.

The more frequently you write, the more confident you become. Spending a small amount of time writing every day is crucial. It develops discipline, and personal discipline is essential if you want to finish a writing project. Maybe you plan to write a novel “someday” but aren’t there yet. Writing random short scenes and vignettes helps develop that story without committing too much time and energy to the project. This is also a good way to create well-rounded characters.

Maybe you plan to write a novel “someday” but aren’t there yet. Writing random short scenes and vignettes helps develop that story without committing too much time and energy to the project. This is also a good way to create well-rounded characters. However,

However,  The Lascaux Review is one of the best contests around. It is exceptionally open to writers who are just beginning their journey. Their fee is reasonable, $15.00 in every category, and submissions are accepted through Submittable.

The Lascaux Review is one of the best contests around. It is exceptionally open to writers who are just beginning their journey. Their fee is reasonable, $15.00 in every category, and submissions are accepted through Submittable.  A way to get a grip on these concepts is what I think of as literary mind-wandering. For me, these ramblings hold the seeds of short stories.

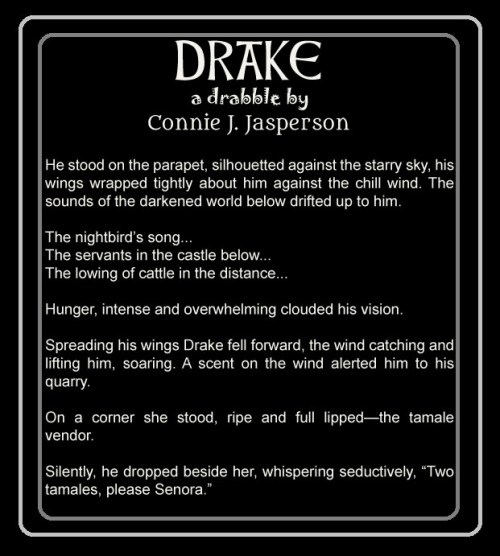

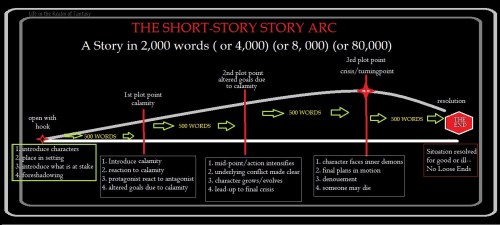

A way to get a grip on these concepts is what I think of as literary mind-wandering. For me, these ramblings hold the seeds of short stories. I break down the word count to know how many words to devote to each act in the story arc. I allow around 25 words to open the story and set the scene. Then, I give myself about 50 – 60 for the heart of the story. That leaves me 10 – 25 words to conclude it.

I break down the word count to know how many words to devote to each act in the story arc. I allow around 25 words to open the story and set the scene. Then, I give myself about 50 – 60 for the heart of the story. That leaves me 10 – 25 words to conclude it. Extremely short fiction is the distilled essence of a novel. It contains everything the reader needs to know and makes them wonder what happened next.

Extremely short fiction is the distilled essence of a novel. It contains everything the reader needs to know and makes them wonder what happened next. I have been busy on the domestic side of things and enjoying life as a Townie. Lovely Instacart delivers my groceries from any store I choose. If we have to be out after dark and it’s raining, I can’t see well, so Uber does the driving. We are living a life of luxury and grateful for it. I have a “passel” of grandbabies and great-grandbabies, so when I have nothing to write, I have needlework projects to keep me busy.

I have been busy on the domestic side of things and enjoying life as a Townie. Lovely Instacart delivers my groceries from any store I choose. If we have to be out after dark and it’s raining, I can’t see well, so Uber does the driving. We are living a life of luxury and grateful for it. I have a “passel” of grandbabies and great-grandbabies, so when I have nothing to write, I have needlework projects to keep me busy. Writing drabbles means your narrative will be limited to one or two characters. There is no room for anything that does not advance the plot or affect the story’s outcome. Also, while a 100-word story takes less time than a 3,000-word story, all writing is a time commitment. I will spend an hour or more getting a drabble to fit within the 100-word constraint.

Writing drabbles means your narrative will be limited to one or two characters. There is no room for anything that does not advance the plot or affect the story’s outcome. Also, while a 100-word story takes less time than a 3,000-word story, all writing is a time commitment. I will spend an hour or more getting a drabble to fit within the 100-word constraint.

Artists:

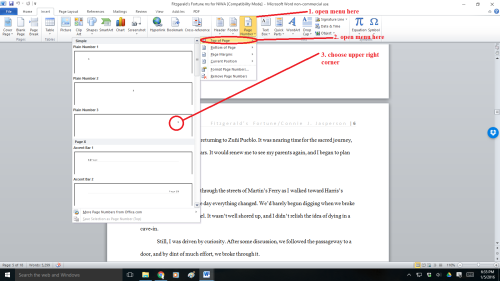

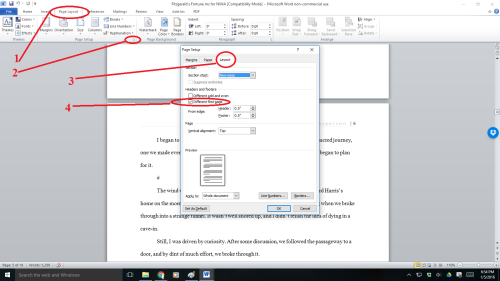

Artists:  This is the heading at the top of each page of a word-processed or faxed document. It contains page numbers, the title, and the author’s name. You won’t need one for most contests. However, if you plan to submit work to a magazine or anthology, you will want your header to follow their guidelines.

This is the heading at the top of each page of a word-processed or faxed document. It contains page numbers, the title, and the author’s name. You won’t need one for most contests. However, if you plan to submit work to a magazine or anthology, you will want your header to follow their guidelines.

So, what do they do if they don’t go over your work line-by-line? Magazine editors look for and bring new and marketable stories to the reading public.

So, what do they do if they don’t go over your work line-by-line? Magazine editors look for and bring new and marketable stories to the reading public. This is because they shouldn’t have to. Before submitting your work to an agent or submissions editor, you must have the technical skills down.

This is because they shouldn’t have to. Before submitting your work to an agent or submissions editor, you must have the technical skills down. When you have a story that you believe in, you must find the venue that publishes your sort of work. Read the magazines you hope to submit work to. That way, you will know what publishers are buying in your genre.

When you have a story that you believe in, you must find the venue that publishes your sort of work. Read the magazines you hope to submit work to. That way, you will know what publishers are buying in your genre. Those who can’t afford to buy magazines can go to websites like

Those who can’t afford to buy magazines can go to websites like For the most part, the requirements are basically the same from contest to contest, with minor differences. Most contests charge a submission fee but have a cash prize if your work is chosen. It doesn’t matter how brilliant your story is; if you don’t follow their guidelines for submission, you will have wasted your money. Non-conforming work will not be read, so follow their guidelines!

For the most part, the requirements are basically the same from contest to contest, with minor differences. Most contests charge a submission fee but have a cash prize if your work is chosen. It doesn’t matter how brilliant your story is; if you don’t follow their guidelines for submission, you will have wasted your money. Non-conforming work will not be read, so follow their guidelines!

You don’t want fancy. Stick with the industry standard fonts: Times New Roman (or rarely Courier) in 12 pt. These are called ‘Serif’ fonts and have little extensions that make letters easier to read when strung together to form words.

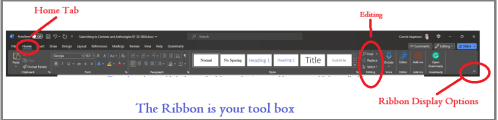

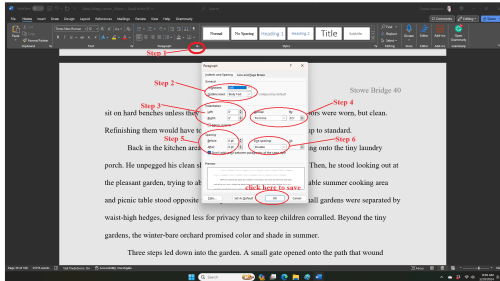

You don’t want fancy. Stick with the industry standard fonts: Times New Roman (or rarely Courier) in 12 pt. These are called ‘Serif’ fonts and have little extensions that make letters easier to read when strung together to form words. To remove tabs from a manuscript in MS Word or most other word-processing programs, open the “Find” box (right side of the ribbon on the home tab). In the “Find” field, type in ^t. (

To remove tabs from a manuscript in MS Word or most other word-processing programs, open the “Find” box (right side of the ribbon on the home tab). In the “Find” field, type in ^t. ( FIRST: SELECT ALL. This will highlight your entire manuscript.

FIRST: SELECT ALL. This will highlight your entire manuscript.

Artist: Paul Cornoyer (1864–1923)

Artist: Paul Cornoyer (1864–1923) You can get your foot in the traditional publishing house door this way. Also, if you are happy as an indie author, having work that places as a finalist in a contest (or is accepted into a paying anthology) will increase your visibility and gain readers for your other work.

You can get your foot in the traditional publishing house door this way. Also, if you are happy as an indie author, having work that places as a finalist in a contest (or is accepted into a paying anthology) will increase your visibility and gain readers for your other work. Many contests and publications use the

Many contests and publications use the  First, let’s be clear–editors don’t enjoy sending out rejections. They want to find the best work by new authors because they love to read. If you have a story that was a contest winner, you may be able to sell it to the right publication.

First, let’s be clear–editors don’t enjoy sending out rejections. They want to find the best work by new authors because they love to read. If you have a story that was a contest winner, you may be able to sell it to the right publication. Each editor for an Anthology or magazine will have a slightly different idea of what they will accept than a literary contest. Literary contests focus heavily on knowledge of craft as well as the ability to tell a story.

Each editor for an Anthology or magazine will have a slightly different idea of what they will accept than a literary contest. Literary contests focus heavily on knowledge of craft as well as the ability to tell a story. Some contests charge a fee for submissions. I’ve said this before, but it bears mentioning again. You have wasted time and money if you don’t follow the prospective contest or publisher’s submission guidelines, which are clearly listed on the contest page on their website.

Some contests charge a fee for submissions. I’ve said this before, but it bears mentioning again. You have wasted time and money if you don’t follow the prospective contest or publisher’s submission guidelines, which are clearly listed on the contest page on their website. It’s hard to hear a critical view of something you have struggled with and labored over. We believe it to be perfect, but we don’t have an objective view of it. This is when you must step back and rethink certain aspects of a piece before you submit it. The external eye of your writing group can help you see the places that don’t work.

It’s hard to hear a critical view of something you have struggled with and labored over. We believe it to be perfect, but we don’t have an objective view of it. This is when you must step back and rethink certain aspects of a piece before you submit it. The external eye of your writing group can help you see the places that don’t work.