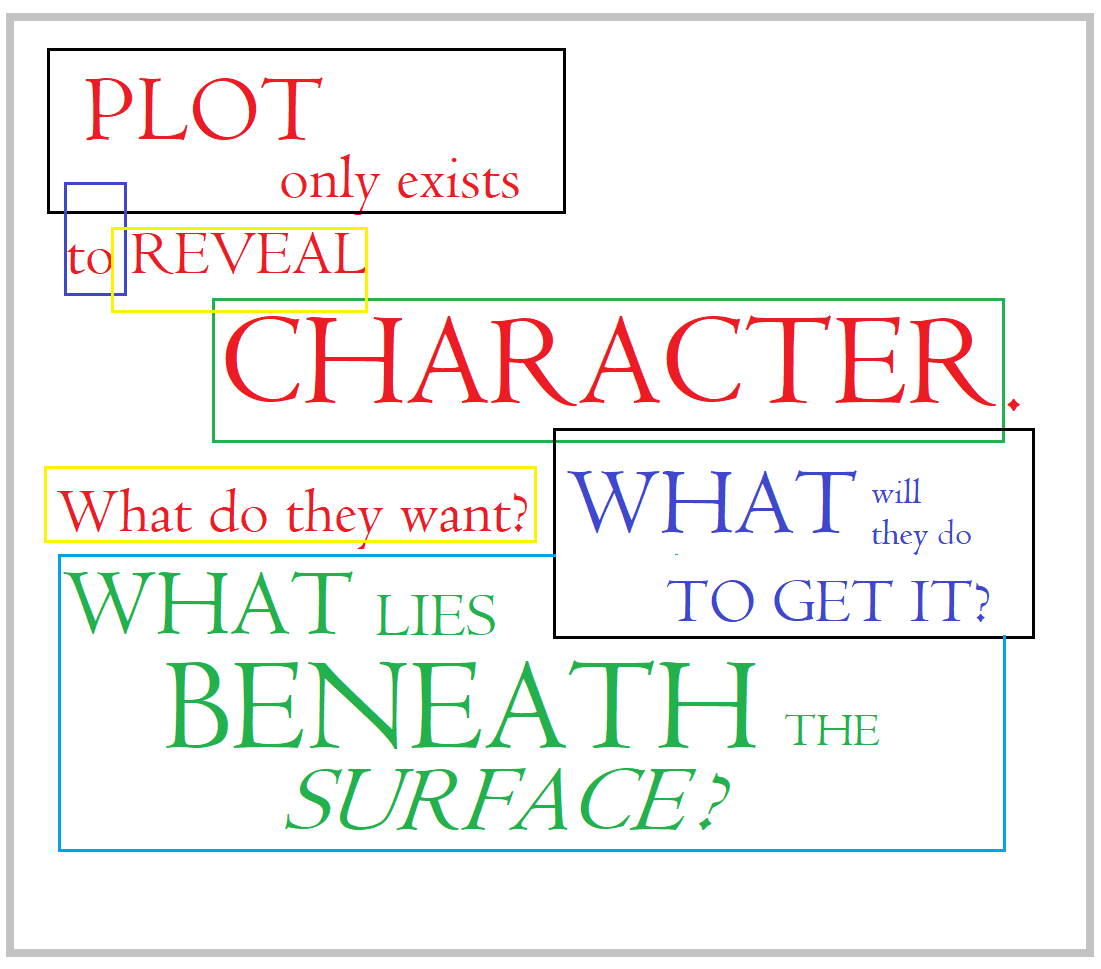

In any environment, fictional or real, the following is true: no matter how costly and rich or poor and rundown, personal belongings in a scene are only necessary for what they say about the people who own them.

Why is this so? Let’s look at an example.

Why is this so? Let’s look at an example.

Consider the protagonist in a scene set in a kitchen.

I cross to sit at the table. In front of me are a laptop, a cup of tea, a notepad, and a pen. The white page of the notepad stares back at me, accusing, as if to say, “Write, you fool.”

But words elude me.

As a reader, what do you see?

You see the word kitchen and assume it is furnished with everything you think should be there. You assume there is a sink, a stove, a refrigerator…and so on. Instantly, it becomes a room you can understand. Yet only the tea, the table, the notepad, and the pen are mentioned. The code word, the one that triggers the mental picture, is kitchen.

If we mention how the dark, heavy furniture lends an atmosphere of gloom to the room, that’s all the description we need to offer. The reader sees the laptop, notepad, and pen, along with a cup of tea against a version of dark and heavy dining furniture. The style of furniture will be something the reader is familiar with.

We don’t need to explain any further.

Possessions that are mentioned give the reader clues about many things. Some things will show economic class and background, but all should hint at the owner’s personality. Are they neat or untidy? Fond of some sort of art? Are there a lot of books? Maybe they are fond of music.

Perhaps they are a person who cares about style, or maybe they don’t. Their possessions reflect their personal tastes.

So how is social class different from economic class? In some parts of the world, they are the same. In others, social class is inherited, and economic class is acquired.

So how is social class different from economic class? In some parts of the world, they are the same. In others, social class is inherited, and economic class is acquired.

When we meet them away from their environment, people’s social class can be hard to nail down just by looking at them. Behavior and manners are one clue, showing the standards and values a person was raised with, irrespective of their financial standing. You’d have to see their family and early lives to know their social class, if class matters to the story.

Most people from impoverished backgrounds are raised with good manners—politeness and respect are personal qualities everyone appreciates. People working in blue-collar jobs are curious about science and the world around them. They might love their work, but they may also value education and go out of their way to educate themselves. They might love all things NASA and look for science shows featuring space exploration.

Many rich families lose their money and social standing over the course of generations. Who they once were no longer means anything. Who they are is all that counts.

Many children who start life in poverty grow up to own expensive clothes and cars, earning them through hard work. So, if you mention a brand name with “cool” status, such as Rolex or iPhone, you are only scraping the surface of the person. You have to go a little deeper, look into their personal values.

Consider the table in our fictional kitchen. Is it a beautiful antique? Maybe it’s a high-quality table from a high-end furniture store. Could it be a secondhand table with mismatched chairs? Or is it a modern-looking matched set from the chain store that sells overpriced furniture on contract and advertises huge discounts on TV, the used-car-salesmen of the furniture world?

We have a good-quality but overpriced matched set in my real-life dining room. What can I say? We are suckers for flashy advertising.

How do we use furnishings to show personality, wealth, background, or class?

People from impoverished backgrounds may value nice things and take care of them because they understand how difficult it can be to acquire replacements. They purchase items as much for durability as for style.

Our personal background formed the first two decades of our lives, but that is all. Once we leave home, that is behind us. Over the next forty to eighty years, life shapes us, forms our likes and dislikes.

For instance, I grew up in a financially stable lower-middle-class family. But I never buy pre-distressed furniture, no matter how much the designers on TV love it. This is because, by the time my youngest child left home, all my hand-me-down furniture was distressed. I like my furniture to reflect my life—un-distressed.

For instance, I grew up in a financially stable lower-middle-class family. But I never buy pre-distressed furniture, no matter how much the designers on TV love it. This is because, by the time my youngest child left home, all my hand-me-down furniture was distressed. I like my furniture to reflect my life—un-distressed.

The way a person dresses and sets out their possessions in their environment can be shown briefly. Clothing, even uniforms, can show personality, and objects can foreshadow things.

The following scene takes place on a starship. The crew is on a scientific mission:

Ensign Kyle Stone left his rooms and walked to Ensign Price’s door on the opposite end of the passage. He pressed the bell, and after a moment, the door slid open. He said, “I might be a bit early. Sorry.” “Kyle” was a name he’d like to lose. “Stone” was what he answered to.

“No problem.” Emma stood there, her uniform perfectly neat, as fresh as if they hadn’t just spent the morning wrangling with a broken levitor. “I’m not quite finished adding this morning’s notes to the brief, so if you don’t mind, I’ll get that done. Have a seat.” She turned and went to the little alcove that served as a study in all the quarters.

Stone sat and looked around, absently wondering how Emma had managed to make the same kind of utilitarian rooms all the unmarried personnel occupied feel so personal, so—lived in. The furnishings were exactly the same as his, built into the floor so you couldn’t rearrange things. Certainly, his quarters looked as personal as a hotel, with only his dirty laundry to show for his existence.

Yet Emma’s quarters had a feeling of permanence. Maybe it was the plants she had set in various places. He noticed a carved wooden box on a shelf above the entertainment console. Beside the box was a framed picture. She never mentioned family, never discussed her personal life. He was about to look more closely at it when she returned.

Emma said, “I uploaded it to Lieutenant Arrans, so we’re all set. Did you manage to find the schematic?”

Glad she hadn’t caught him snooping in her personal space, Stone said, “I did, and uploaded them. But I still doubt it’s what we need.”

Still talking, they left Emma’s quarters, heading to the small conference room.

What does the box signify? Who is in the picture? What did Stone’s observation of Emma’s tidy uniform and her plants tell you about her? How do these things relate to the larger story?

Sunset at Tillamook Head, Copyright 2016 Connie J. Jasperson

In a sci-fi story, just as in a contemporary or fantasy story, the way we use observations and visuals says a lot about our characters, things we don’t have to write out in detail.

Use these visual observations to your advantage.

Your assignment is this:

Invent two characters and write a short scene set in any room, any genre. Be selective in the visual items you mention and only mention the things the protagonist finds important.

Readers will extrapolate information from those items, clues that will build an entire picture in their imaginations, populating the space with many things you won’t have to mention.

February here in my little town was dryer than usual, far less rainy than in other parts of the Northwest. We have seen the sun much more than usual over the last two weeks, which doesn’t bode well for the summer. I can’t help but think of the horrible heat we had last June. We don’t like it when it gets up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43.3 Celsius). It’s literally hell when you realize most people here don’t have air conditioning in their homes. Up through the 1980s, we never needed it, as summers rarely topped 80 degrees (26.6).

February here in my little town was dryer than usual, far less rainy than in other parts of the Northwest. We have seen the sun much more than usual over the last two weeks, which doesn’t bode well for the summer. I can’t help but think of the horrible heat we had last June. We don’t like it when it gets up to 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43.3 Celsius). It’s literally hell when you realize most people here don’t have air conditioning in their homes. Up through the 1980s, we never needed it, as summers rarely topped 80 degrees (26.6). Edible mushrooms of all sorts abounded. One I hadn’t seen before, the lion’s mane mushroom, was the central feature in the displays of the two local craft fungi growers. It was interesting to look at, but … no.

Edible mushrooms of all sorts abounded. One I hadn’t seen before, the lion’s mane mushroom, was the central feature in the displays of the two local craft fungi growers. It was interesting to look at, but … no. On the writing front, last week was quite productive. I received the final chapters back for my blended novel from my editor and am now going over the manuscript one last time. This is a merging of the stories of two characters and the events of one overarching plot arc. It’s the parallel stories of two battle mages, a father and son, told from their unique generational viewpoints.

On the writing front, last week was quite productive. I received the final chapters back for my blended novel from my editor and am now going over the manuscript one last time. This is a merging of the stories of two characters and the events of one overarching plot arc. It’s the parallel stories of two battle mages, a father and son, told from their unique generational viewpoints. This merger of two novels into one involved cutting a number of chapters out of each and layering the stories so that the timeline moves forward at the right pace and doesn’t repeat what we already know.

This merger of two novels into one involved cutting a number of chapters out of each and layering the stories so that the timeline moves forward at the right pace and doesn’t repeat what we already know. Also, I submitted my 2020 NaNoWriMo novel to

Also, I submitted my 2020 NaNoWriMo novel to  Today we are discussing a particular kind of editor: the submissions editor. When I first began this journey, I didn’t understand how specifically you have to tailor your submissions for literary magazines, contests, and anthologies. Each publication has a specific market of readers, and their editors look for new works their target market will buy.

Today we are discussing a particular kind of editor: the submissions editor. When I first began this journey, I didn’t understand how specifically you have to tailor your submissions for literary magazines, contests, and anthologies. Each publication has a specific market of readers, and their editors look for new works their target market will buy. The quality of your work isn’t the problem, and you have selected a publication that features work in your chosen genre. But your subgenre may not match what the readers of that publication want to see. After all, both spaghetti Bolognese and bruschetta are created out of ingredients made from wheat and tomatoes, but the finished meals are vastly different.

The quality of your work isn’t the problem, and you have selected a publication that features work in your chosen genre. But your subgenre may not match what the readers of that publication want to see. After all, both spaghetti Bolognese and bruschetta are created out of ingredients made from wheat and tomatoes, but the finished meals are vastly different. Some hobbyists expect special consideration and are offended when they don’t get it. Egos are rampant in this business, but in reality, no one gets to be treated like a princess.

Some hobbyists expect special consideration and are offended when they don’t get it. Egos are rampant in this business, but in reality, no one gets to be treated like a princess. er sending your work.

er sending your work. Please, if you consider yourself a professional, format your submissions properly. You want to stand out but getting fancy with your final manuscript is not the way to do that—you will be rejected out of hand if you don’t make this effort.

Please, if you consider yourself a professional, format your submissions properly. You want to stand out but getting fancy with your final manuscript is not the way to do that—you will be rejected out of hand if you don’t make this effort. For new and beginning authors, it may take an editor more than one trip through a manuscript to straighten out all the kinks. This may be a three-step process involving you making the first round of revisions and/or explanations, sending them back to the editor, who will make final round of suggestions. At that point, the editor is done. You have the choice to either accept or reject those suggestions in your final manuscript.

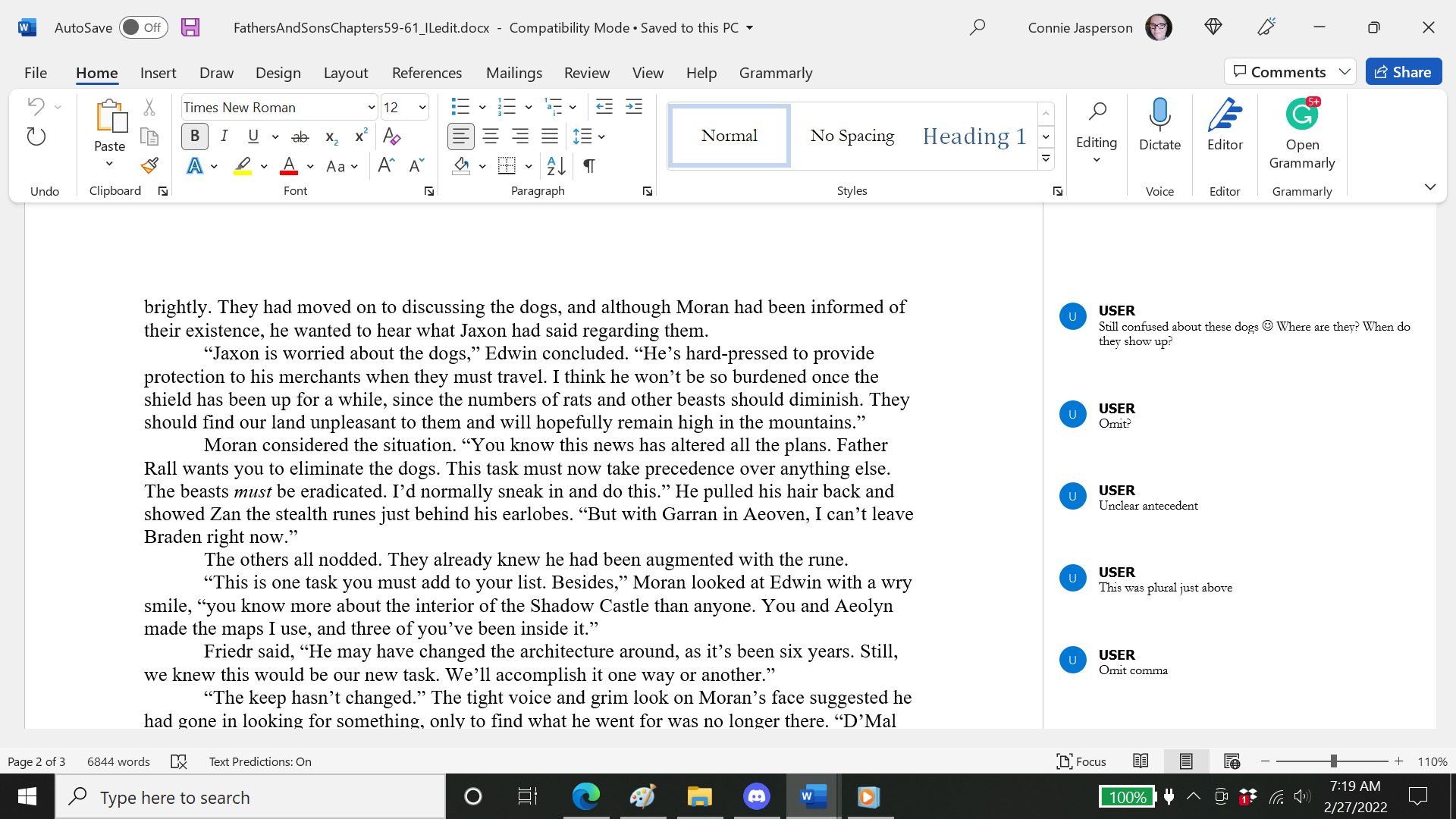

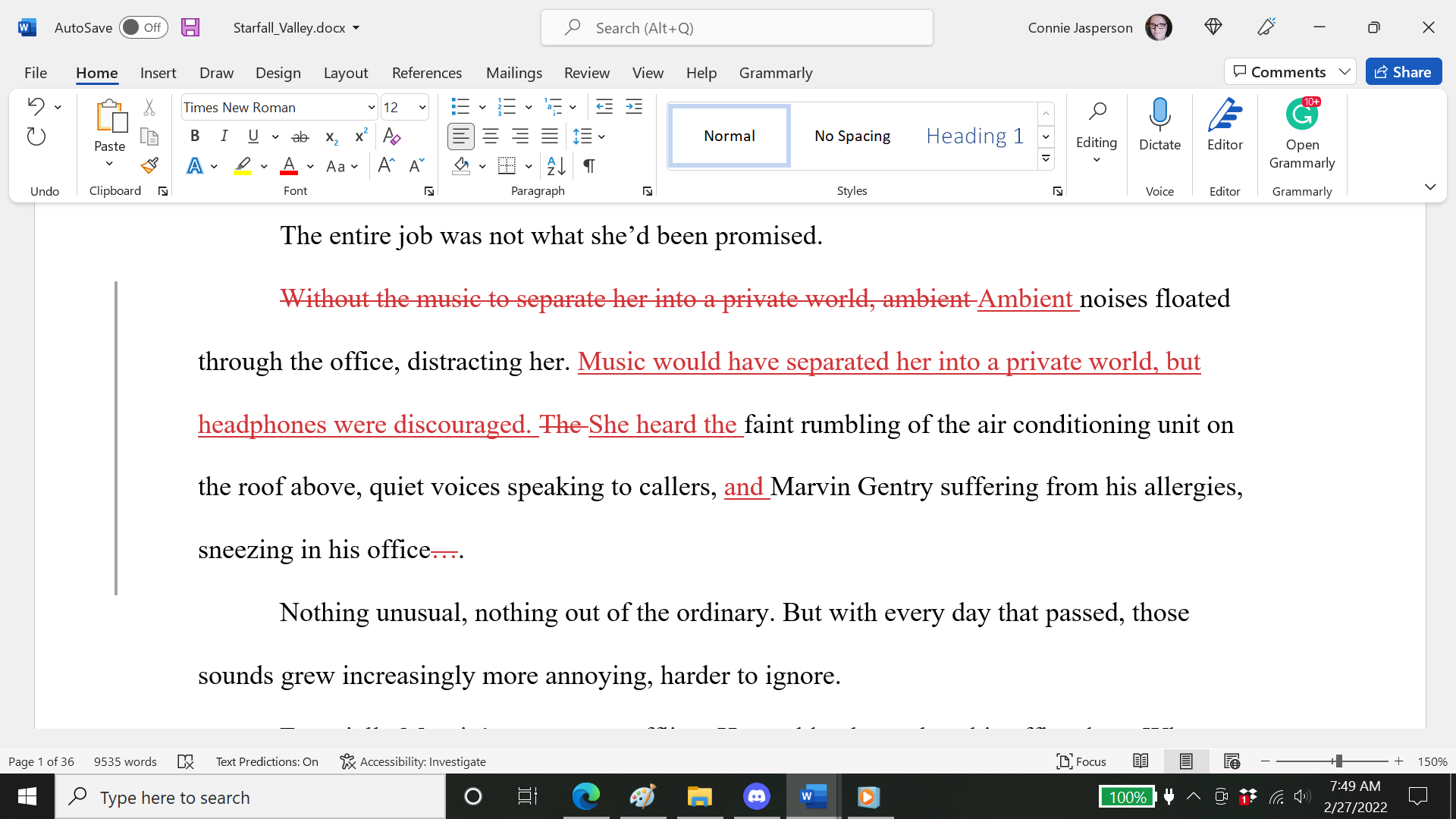

For new and beginning authors, it may take an editor more than one trip through a manuscript to straighten out all the kinks. This may be a three-step process involving you making the first round of revisions and/or explanations, sending them back to the editor, who will make final round of suggestions. At that point, the editor is done. You have the choice to either accept or reject those suggestions in your final manuscript. For creative writing, editing is a stage of the writing process. A writer and editor work together to improve a draft by correcting punctuation and making words and sentences clearer, more precise. Weak sentences are made stronger, info dumps are weeded out, and important ideas are clarified. At the same time, strict attention is paid to the overall story arc.

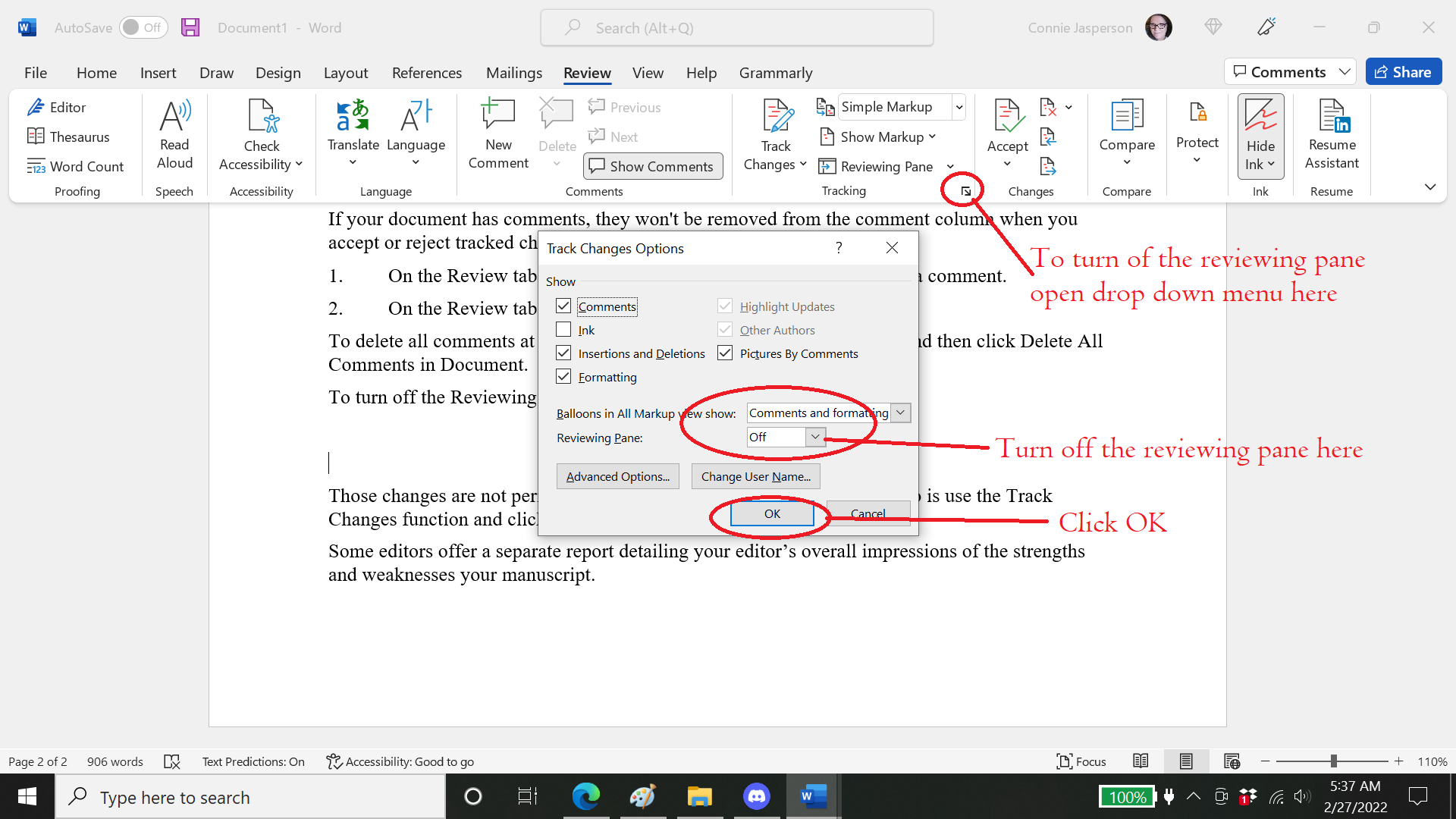

For creative writing, editing is a stage of the writing process. A writer and editor work together to improve a draft by correcting punctuation and making words and sentences clearer, more precise. Weak sentences are made stronger, info dumps are weeded out, and important ideas are clarified. At the same time, strict attention is paid to the overall story arc. Editors who have been in the business for a long time find it much faster to use the markup function and insert inline changes. A new author or someone unfamiliar with how word-processing programs work might find it confusing and difficult to understand.

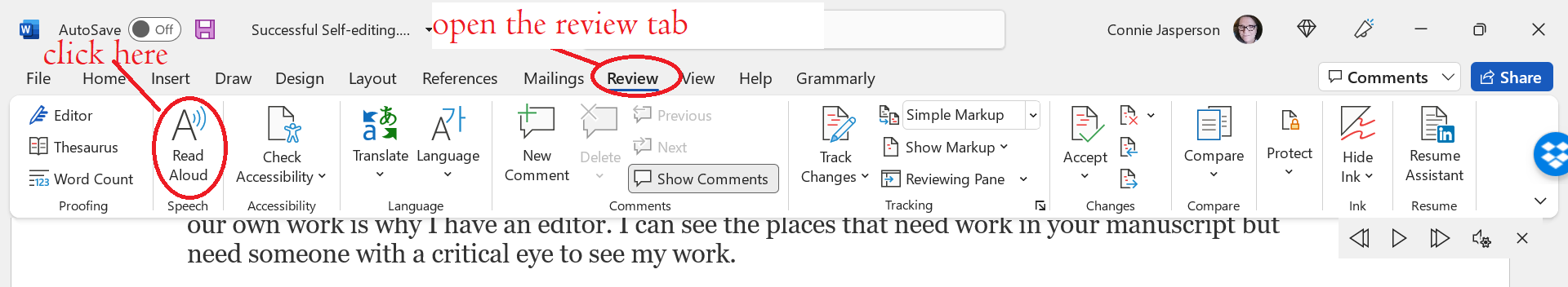

Editors who have been in the business for a long time find it much faster to use the markup function and insert inline changes. A new author or someone unfamiliar with how word-processing programs work might find it confusing and difficult to understand. Inserting the changes and using Tracking cuts the time an editor spends on a manuscript. Writing comments takes time, and suggestions may not always be clear to the client.

Inserting the changes and using Tracking cuts the time an editor spends on a manuscript. Writing comments takes time, and suggestions may not always be clear to the client.

However, many authors don’t have the money to hire an editor. If that is the case, you may have a friend in your writing group who has some experience editing, and they will often help you at no cost. Your writing group is a well of inspiration, support, and wisdom, and they are invested in your book. They want you to succeed and most will gladly trade services.

However, many authors don’t have the money to hire an editor. If that is the case, you may have a friend in your writing group who has some experience editing, and they will often help you at no cost. Your writing group is a well of inspiration, support, and wisdom, and they are invested in your book. They want you to succeed and most will gladly trade services. When I am finished with the revisions, I will format my manuscript as both ebooks and paper books. At that point, I will be looking for proofreaders.

When I am finished with the revisions, I will format my manuscript as both ebooks and paper books. At that point, I will be looking for proofreaders. If you didn’t see it when I mentioned it above, I will repeat it: proofreading is not editing. We discussed self-editing in my previous post,

If you didn’t see it when I mentioned it above, I will repeat it: proofreading is not editing. We discussed self-editing in my previous post, Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These happen when making revisions, even by the most meticulous of authors. The editor won’t see any mistakes you introduce after they have completed their work on the manuscript.

Repeated words and cut-and-paste errors. These happen when making revisions, even by the most meticulous of authors. The editor won’t see any mistakes you introduce after they have completed their work on the manuscript. Unfortunately, my last book went live when I thought I was ordering a pre-publication proof.

Unfortunately, my last book went live when I thought I was ordering a pre-publication proof. So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection.

So, realizing I knew nothing was the first positive thing I did for myself. I made it my business to learn all I could, even though I will never achieve perfection. I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is.

I use this function rather than reading it aloud myself, as I tend to see and read aloud what I think should be there rather than what is. This is a long process that involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through an entire 90,000-word manuscript. I will have trimmed about 3,000 words by the end of phase one. I will have caught many typos and miskeyed words and rewritten many clumsy sentences.

This is a long process that involves a lot of stopping and starting, taking me a week to get through an entire 90,000-word manuscript. I will have trimmed about 3,000 words by the end of phase one. I will have caught many typos and miskeyed words and rewritten many clumsy sentences. This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination.

This is the phase where I look for info dumps, passive phrasing, and timid words. These telling passages are codes for the author, laid down in the first draft. They are signs that a section needs rewriting to make it visual rather than telling. Clunky phrasing and info dumps are signals telling me what I intend that scene to be. I must cut some of the info and allow the reader to use their imagination. Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess.

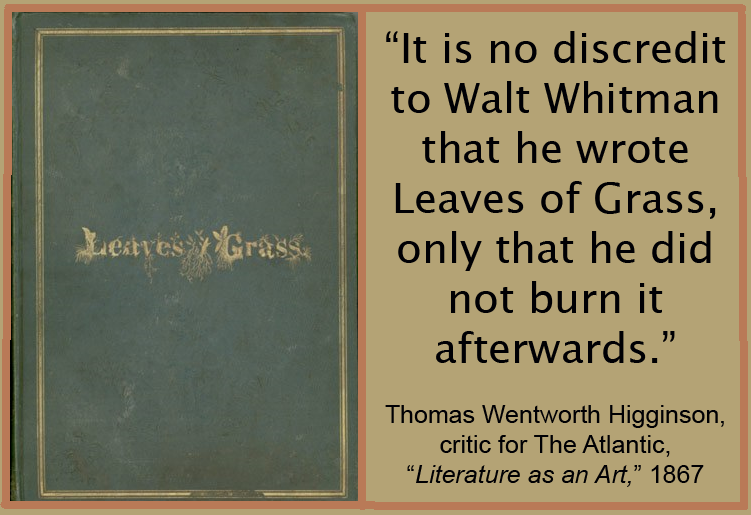

Editing programs operate on algorithms and don’t understand context. I am wary of relying on Grammarly or ProWriting Aid for anything other than alerting you to possible problems. If you blindly obey every suggestion made by editing programs, you will turn your manuscript into a mess. I wrote poetry and lyrics for a heavy metal band when I first started out. I was young, sincere, and convinced I had to impart a message with every word. I didn’t know until twenty years later when I came across my old notebook that my poems weren’t honest. Eighteen-year-old me was trying to make a point rather than offering ideas for further thought.

I wrote poetry and lyrics for a heavy metal band when I first started out. I was young, sincere, and convinced I had to impart a message with every word. I didn’t know until twenty years later when I came across my old notebook that my poems weren’t honest. Eighteen-year-old me was trying to make a point rather than offering ideas for further thought. Children are unimpressed by the fact their parents might write a story or play music or paint or do any of the creative arts.

Children are unimpressed by the fact their parents might write a story or play music or paint or do any of the creative arts. As Ursula K. LeGuin said in her excellent book,

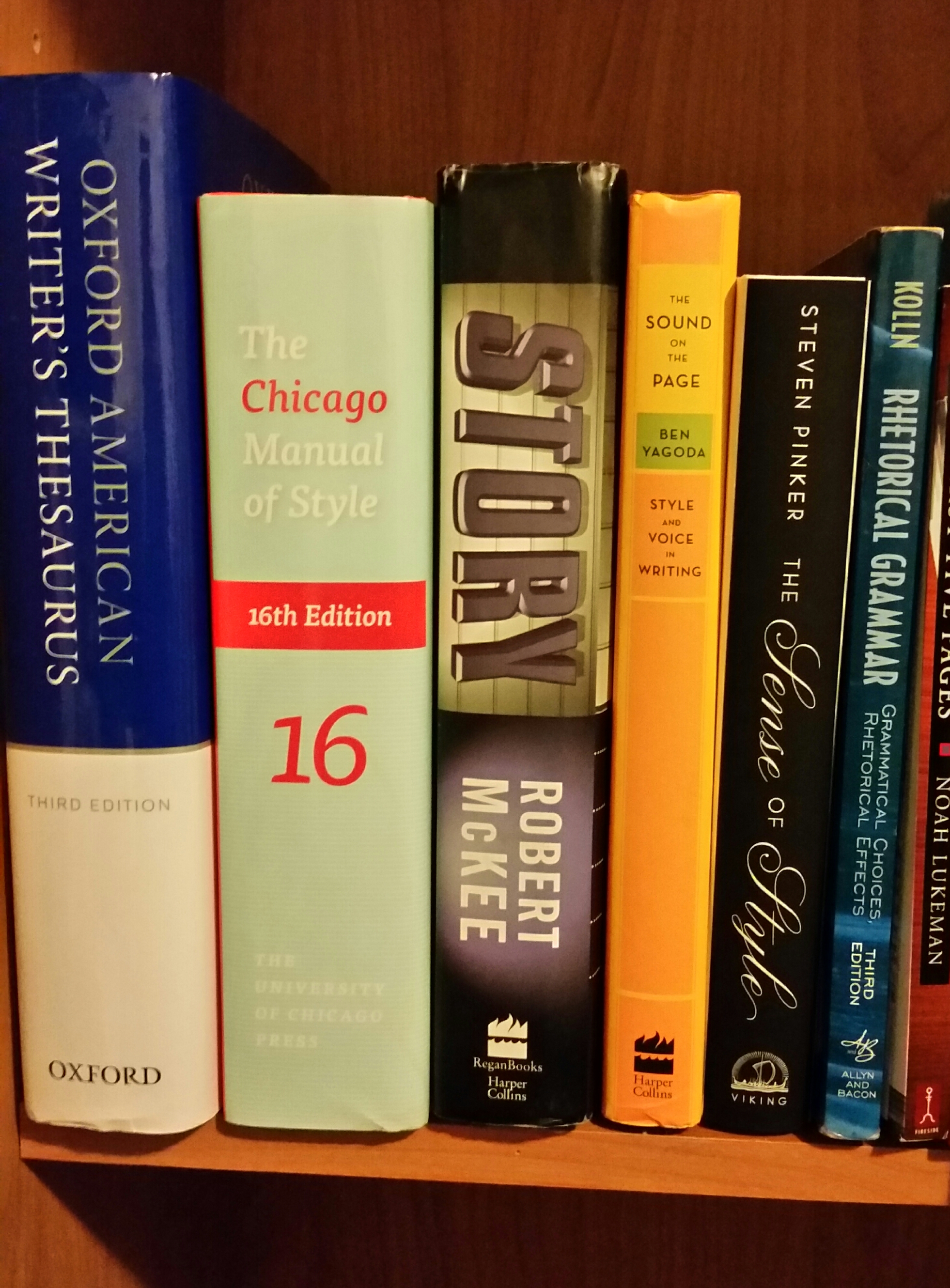

As Ursula K. LeGuin said in her excellent book,  day, should we so desire. Reading is how we come to understand writing and the art of story. Mr. King also admonishes us to learn the fundamentals of punctuation and grammar.

day, should we so desire. Reading is how we come to understand writing and the art of story. Mr. King also admonishes us to learn the fundamentals of punctuation and grammar. Every editor will tell you no amount of money is worth the time and effort it would take to teach an author how to write coherent, readable prose. That is what seminars, books on craft, and books on style and grammar are for.

Every editor will tell you no amount of money is worth the time and effort it would take to teach an author how to write coherent, readable prose. That is what seminars, books on craft, and books on style and grammar are for. I want to read an honest story about people who seem real, who have the kind of problems we can all relate to on a human level. I want to read a story that comes from an author’s deepest soul. The setting doesn’t matter—it can be set on Mars or in Africa. Characters matter, and their story matters.

I want to read an honest story about people who seem real, who have the kind of problems we can all relate to on a human level. I want to read a story that comes from an author’s deepest soul. The setting doesn’t matter—it can be set on Mars or in Africa. Characters matter, and their story matters. Actually, my large dirty minivan is not as comfortable to ride in as it used to be. Grandma’s imaginary red Ferrari would be a lot more fun, but alas—if wishes were Ferraris, my driveway would look a lot fancier.

Actually, my large dirty minivan is not as comfortable to ride in as it used to be. Grandma’s imaginary red Ferrari would be a lot more fun, but alas—if wishes were Ferraris, my driveway would look a lot fancier. Have you ever wondered why we say fiddle-faddle and not faddle-fiddle? Why is it ping-pong and pitter-patter rather than pong-ping and patter-pitter? Why dribs and drabs rather than vice versa? Why can’t a kitchen be span and spic? Whence riff-raff, mishmash, flim-flam, chit-chat, tit for tat, knick-knack, zig-zag, sing-song, ding-dong, King Kong, criss-cross, shilly-shally, seesaw, hee-haw, flip-flop, hippity-hop, tick-tock, tic-tac-toe, eeny-meeny-miney-moe, bric-a-brac, clickey-clack, hickory-dickory-dock, kit and kaboodle, and bibbity-bobbity-boo? The answer is that the vowels for which the tongue is high and in the front always come before the vowels for which the tongue is low and in the back. (Pinker, The Language Instinct, 1994:167) [3]

Have you ever wondered why we say fiddle-faddle and not faddle-fiddle? Why is it ping-pong and pitter-patter rather than pong-ping and patter-pitter? Why dribs and drabs rather than vice versa? Why can’t a kitchen be span and spic? Whence riff-raff, mishmash, flim-flam, chit-chat, tit for tat, knick-knack, zig-zag, sing-song, ding-dong, King Kong, criss-cross, shilly-shally, seesaw, hee-haw, flip-flop, hippity-hop, tick-tock, tic-tac-toe, eeny-meeny-miney-moe, bric-a-brac, clickey-clack, hickory-dickory-dock, kit and kaboodle, and bibbity-bobbity-boo? The answer is that the vowels for which the tongue is high and in the front always come before the vowels for which the tongue is low and in the back. (Pinker, The Language Instinct, 1994:167) [3] We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names.

We all draw inspiration from real life, whether consciously or not. However, if we are writing fiction, we must never detail people we are acquainted with, even if we change their names. The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous.

The best thing is that you don’t actually know a thing about them other than they like a Double Tall Hazelnut Latte. Peoples’ conversations are unguarded in coffee shops, openly talking about what moves them or holds them back. They are lovers or haters, quiet or loud, and most importantly, anonymous. Several years ago, I read a fantasy book where the author clearly spent many hours on the food of her fantasy world and the various animals. She gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture.

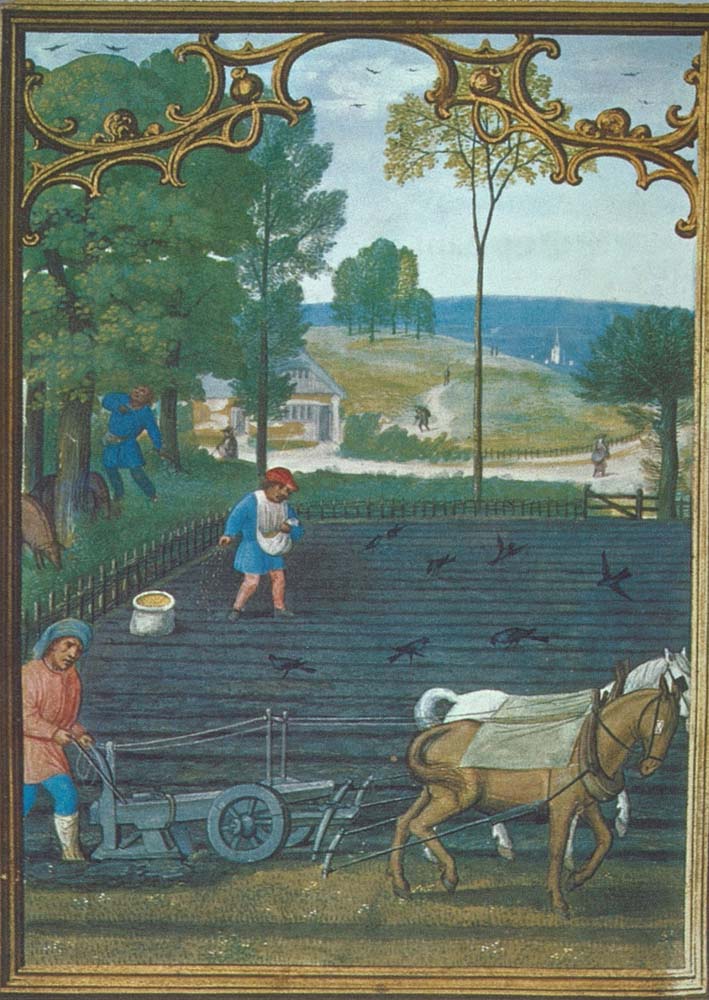

Several years ago, I read a fantasy book where the author clearly spent many hours on the food of her fantasy world and the various animals. She gave each kind of fruit, bird, or herd beast a different, usually unpronounceable, name in the language of her fantasy culture. As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep. Most of the meat we served in our home was raised on his family’s communal farm. Our chickens and rabbits roamed their yard and had good lives, and our family’s herd of twenty sheep was managed using simple, old-style farming methods.

As many of you know, I have been vegan since 2012. However, during the 1980s, my second ex-husband and I raised sheep. Most of the meat we served in our home was raised on his family’s communal farm. Our chickens and rabbits roamed their yard and had good lives, and our family’s herd of twenty sheep was managed using simple, old-style farming methods.

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. In

Knowing what to feed your people keeps you from introducing jarring components into your narrative. In