I am not good at winging it when plotting a novel. I might begin with nothing but a few characters and a loose idea for a plot, but somewhere toward the middle, I will lose momentum.

I will have to spend a day or two thinking about the story as a whole and writing an outline as a framework to guide the story. The plot points I originally planned to occur at each of the four quarters of the story will be met, but how?

I will have to spend a day or two thinking about the story as a whole and writing an outline as a framework to guide the story. The plot points I originally planned to occur at each of the four quarters of the story will be met, but how?

In my head, I know that character plus objective plus risk equals a story. In practice, it’s more complicated than it looks.

Every story begins with the opening act, introducing the characters and setting the scene. It then kicks into gear with the occurrence of the “inciting incident,” that first plot point that triggers the rest of the story.

I’m very good at getting this part on paper. But here is where my storytelling skills sometimes fail me.

At the midpoint of my outline, another serious incident is scheduled to occur, an event setting them back even further. They will be aware that they may not achieve their objectives after all.

While I know that bad things have to happen at this place, I sometimes can’t figure out what those things are.

In my logical mind, I know that the protagonists must get creative and work hard to achieve their desired goals. I know they must overcome their doubts and make themselves stronger.

But what are those doubts?

We have arrived at the first pinch point. The characters are on the hunt for the MacGuffin. The antagonist makes an appearance, and the heroes survive the first roadblock and—

Nothing.

This sudden blank wall is where creating an outline comes into play. But since I know what the ending is that I must write to, I approach this part of the outline as if I were writing a murder mystery.

When I can’t figure out the middle, I start at the end of my story and work my way backward until I have joined the dots connecting the ending to the beginning.

Crime writers ask themselves several things when they begin plotting a mystery. We can all learn from their method:

- What crime was committed?

- Who committed the crime?

- How did they pull it off?

- Why did they do it?

So, I look at what I originally planned for the ending and ask, “What led us to this point?”

The midpoint of the story arc is often where the protagonists lose their faith or have a crisis of conscience. Something terrible happens, and they must learn to live with it.

The midpoint of the story arc is often where the protagonists lose their faith or have a crisis of conscience. Something terrible happens, and they must learn to live with it.

What was that terrible thing?

Maybe the protagonist has suffered a terrible personal loss or setback. Because of this, maybe she no longer believes in herself or the people she once looked up to.

How was her own personal weakness responsible for this turn of events?

How does this cause the protagonist to question everything she ever believed in?

What gives her the strength and the courage to pull herself together and finish the job?

How is she different after this personal death and rebirth event?

This midpoint crisis is where the protagonist makes the hard decisions and learns she truly has the courage to do the job. The antagonist has had their day in the sun and could possibly win.

What I sometimes forget is this: plot arcs hinge on our characters and their reasons for being there. No matter what genre we’re writing in, giving the individual players strong motivations makes the story easier to write.

If I haven’t made their motivations strong enough by the midpoint, I will lose track of the plot.

At the beginning of my story, I will know what “the crime” is, the incident that throws my characters into the action. I never lose track of that—it’s the middle that gets mushy for me.

I will know who the antagonist is and why they are acting against my main characters. I will even know why it is all happening.

The part I struggle with is the how.

So, starting at the end, I look at my characters’ location when the story finishes. Then I ask myself what they were doing just before the final encounter.

So, starting at the end, I look at my characters’ location when the story finishes. Then I ask myself what they were doing just before the final encounter.

And before they did that, what were they doing? What did they accomplish to move the story forward to that place? What location did they begin that part of the journey from, and why were they there?

I work my way backward through each step of the problem. It’s not a perfect method, and may not work for everyone. But by working in reverse from a known point, I can see what needs to happen and begin to write the story again.

This happens even when I have an outline. I will get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

This happens even when I have an outline. I will get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious. He says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

He says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?” “Look, why don’t you sit here and watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker.

“Look, why don’t you sit here and watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker. “I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

At first, getting your books in front of readers is a challenge. The in-person sales event is one way to get eyes on your books. This could be at a venue as small as a local bookstore allowing you to set up a table on their premises.

At first, getting your books in front of readers is a challenge. The in-person sales event is one way to get eyes on your books. This could be at a venue as small as a local bookstore allowing you to set up a table on their premises.

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  I suggest buying book stands of some sort. Recipe stands work, as do plate and picture stands. Whether they’re fancy or cheap, be sure you know how to use them properly so they aren’t falling over when someone bumps the table. I use folding plate stands as they store well in the rolling suitcase I use for my supplies.

I suggest buying book stands of some sort. Recipe stands work, as do plate and picture stands. Whether they’re fancy or cheap, be sure you know how to use them properly so they aren’t falling over when someone bumps the table. I use folding plate stands as they store well in the rolling suitcase I use for my supplies. If you plan to get a table at a large conference this year, I highly recommend

If you plan to get a table at a large conference this year, I highly recommend  But when it comes to having a website, don’t sweat it. WordPress and Blogger (Google’s platform) offer free blogs and theme templates. You can have a nice-looking website, with only a small amount of effort and a little self-education.

But when it comes to having a website, don’t sweat it. WordPress and Blogger (Google’s platform) offer free blogs and theme templates. You can have a nice-looking website, with only a small amount of effort and a little self-education. A blog post doesn’t have to be long. Think of it as a slightly longer tweet or Facebook post. Just write a paragraph or two about what you are interested in at that moment. You will have 300 – 500 words written in no time.

A blog post doesn’t have to be long. Think of it as a slightly longer tweet or Facebook post. Just write a paragraph or two about what you are interested in at that moment. You will have 300 – 500 words written in no time.

After six months, you’ll have a history of stats to look at. Use that information to gauge what topics did best. Make sure the time the blog goes live is a good slot. You want to post it when people are looking for something short to read, like when riding the bus or train to or from work.

After six months, you’ll have a history of stats to look at. Use that information to gauge what topics did best. Make sure the time the blog goes live is a good slot. You want to post it when people are looking for something short to read, like when riding the bus or train to or from work. If you enjoy reading magazines like

If you enjoy reading magazines like  The narrative essay conveys our experiences and ideas in a form that is easy to digest, so writing this kind of piece requires authors to have some idea of the craft of writing.

The narrative essay conveys our experiences and ideas in a form that is easy to digest, so writing this kind of piece requires authors to have some idea of the craft of writing. A narrative essay is a story that begins with an experience you once had. You know how that event began and ended. Just like any other form of short fiction, a narrative essay has a plot arc.

A narrative essay is a story that begins with an experience you once had. You know how that event began and ended. Just like any other form of short fiction, a narrative essay has a plot arc. We don’t want to disclose too much information about ourselves or the people we have encountered. An honest narrative essay contains an author’s opinions. Sometimes those sentiments are not glowing accolades. One can lose friends if they aren’t careful.

We don’t want to disclose too much information about ourselves or the people we have encountered. An honest narrative essay contains an author’s opinions. Sometimes those sentiments are not glowing accolades. One can lose friends if they aren’t careful.

Take some time to review what you submitted, keeping those comments in mind. Then form a plan to address those issues with a rewrite.

Take some time to review what you submitted, keeping those comments in mind. Then form a plan to address those issues with a rewrite. When a new writer decides to begin their career by embarking on writing a novel, the magnitude of the undertaking soon becomes apparent.

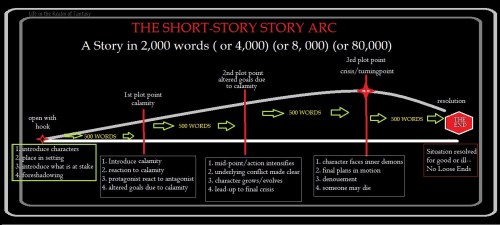

When a new writer decides to begin their career by embarking on writing a novel, the magnitude of the undertaking soon becomes apparent. I use a loose outline to break the arc of every story I write into acts, each with a specific word count. (I’ve included a graphic at the bottom of this post.)

I use a loose outline to break the arc of every story I write into acts, each with a specific word count. (I’ve included a graphic at the bottom of this post.) I mentioned rewards in the title of this post. The completed story is a small gift you give yourself, and the surge of endorphins you experience in that moment of “Yes! I can write after all!” are the reward.

I mentioned rewards in the title of this post. The completed story is a small gift you give yourself, and the surge of endorphins you experience in that moment of “Yes! I can write after all!” are the reward.

We humans are tribal. We prefer an overarching power structure leading us because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government.

We humans are tribal. We prefer an overarching power structure leading us because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government. Power structures are the hierarchies encompassing the leaders and the people with the power. Government is an overall system of restraint and control among selected members of a group. Think of it as a pyramid, a few at the top governing a wide base of citizens.

Power structures are the hierarchies encompassing the leaders and the people with the power. Government is an overall system of restraint and control among selected members of a group. Think of it as a pyramid, a few at the top governing a wide base of citizens.

The same sort of God complex occurs among academicians and scientists. Some people are prone to excess when presented with the opportunity to become all-powerful.

The same sort of God complex occurs among academicians and scientists. Some people are prone to excess when presented with the opportunity to become all-powerful. Some people call this writers’ block. I think of it as a temporary lull in my creativity.

Some people call this writers’ block. I think of it as a temporary lull in my creativity. Sometimes, the problem is that your mind has seen a shiny thing, a different project that wants to be written, and you can’t focus on the job at hand. If that is the case, work on the project that is on your mind. Let that creative energy flow, and you can reconnect with the first project once the new project is out of the way.

Sometimes, the problem is that your mind has seen a shiny thing, a different project that wants to be written, and you can’t focus on the job at hand. If that is the case, work on the project that is on your mind. Let that creative energy flow, and you can reconnect with the first project once the new project is out of the way.

In my real life, getting our house ready to put on the market saps my creativity, but I am muddling along. Boxes here and there, getting rid of this and that—it’s exhausting. Sometimes I don’t have the energy to write.

In my real life, getting our house ready to put on the market saps my creativity, but I am muddling along. Boxes here and there, getting rid of this and that—it’s exhausting. Sometimes I don’t have the energy to write. When we daydream, our brain is free to process tasks more effectively.

When we daydream, our brain is free to process tasks more effectively. Every writer knows the backstory is what tells us who the characters are as people and why they’re the way they are. At the beginning of our career, it seems logical to inform the reader of that history upfront. “Before you can understand that, you need to know this.”

Every writer knows the backstory is what tells us who the characters are as people and why they’re the way they are. At the beginning of our career, it seems logical to inform the reader of that history upfront. “Before you can understand that, you need to know this.” But knowing this and putting it into action are two different things.

But knowing this and putting it into action are two different things. Be aware: if you are writing from an omniscient POV, this can be tricky and lead to “

Be aware: if you are writing from an omniscient POV, this can be tricky and lead to “ Romance novels average 50,000 to 70,000 words. In shorter novels, there is no room for sweeping, epic backstories. Instead, information and backstory are meted out only as needed through conversations and internal dialogue/introspection.

Romance novels average 50,000 to 70,000 words. In shorter novels, there is no room for sweeping, epic backstories. Instead, information and backstory are meted out only as needed through conversations and internal dialogue/introspection. Even with all the effort I apply to it, my editor will find things that don’t matter. She will gently take a metaphorical axe to it, highlighting that which doesn’t advance the story or add to the intrigue.

Even with all the effort I apply to it, my editor will find things that don’t matter. She will gently take a metaphorical axe to it, highlighting that which doesn’t advance the story or add to the intrigue. In his book,

In his book,  Batman is a

Batman is a  Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the

Apollo 13 (April 11–17, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the