A reader’s perception of a narrative’s reality is affected by emotions they aren’t even aware of, an experience created by the layers of worldbuilding.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

Mood and atmosphere are separate but entwined forces. They form subliminal impressions in the reader’s awareness, subcurrents that affect our personal emotions.

The emotions evoked in readers as they experience the story are created by the combination of mood, atmosphere, and subtext.

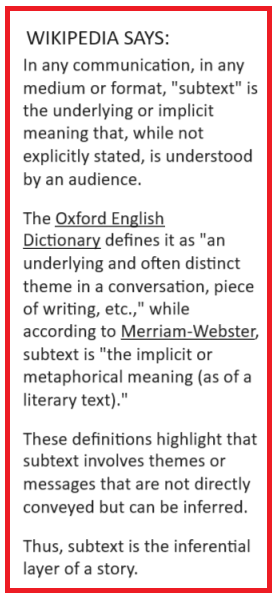

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Subtext is a complex but essential aspect of storytelling. It lies below the surface and supports the plot and the conversations. It is the hidden story, the secret reasoning we deduce from the narrative. It’s conveyed by the images we place in the environment and how the setting influences our perception of the mood and atmosphere.

Emotion is the experience of contrasts, of transitioning from the negative to the positive and back again. Mood, atmosphere, and emotion are part of the inferential layer of a story, part of the subtext. When an author has done their job well, the reader experiences the emotional transitions as the characters do. It is our job to make those transitions feel personal.

The atmosphere of a story is long-term. Atmosphere is the aspect of mood that is conveyed by the setting as well as the general emotional state of the characters.

The mood of a story is also long-term, but it is a feeling residing in the background, going almost unnoticed. Mood shapes (and is shaped by) the emotions evoked within the story.

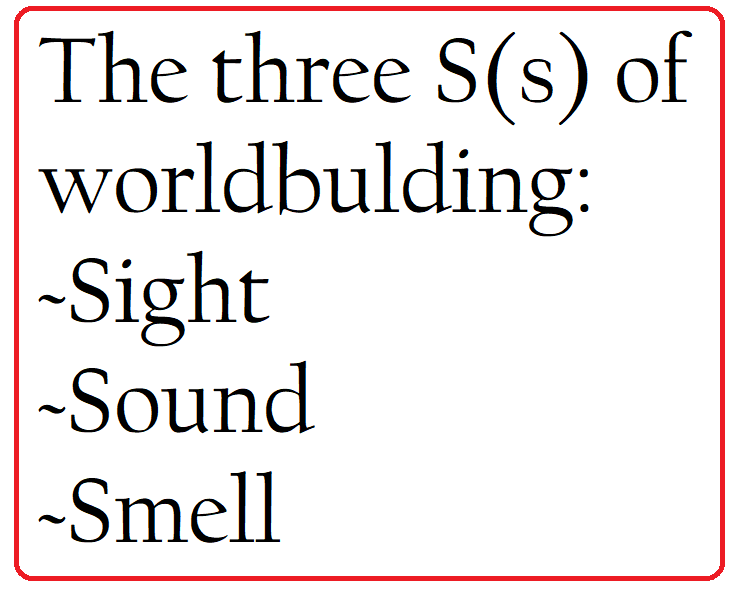

Scene framing is the order in which we stage the people and the visual objects we include in a scene, as well as the sequence of scenes along the plot arc. It shapes the overall mood and atmosphere and contributes to the subtext. We choose the furnishings, sounds, and odors that are the visual necessities for that scene, and we place the scenes in a logical, sequential order.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

We want to avoid excessive exposition, and good worldbuilding can help us with that. Let’s say we want to convey a general atmosphere of gloom and show our character’s mood without an info dump. Environmental symbols are subliminal landmarks for the reader. Thinking about and planning symbolism in an environment is key to developing the general atmosphere and affecting the overall mood.

Barren landscapes and low windswept hills feel cold and dark to me. The word gothic in a novel’s description tells me it will be a dark, moody piece set in a stark, desolate environment. A cold, barren landscape, constant dampness, and continually gray skies set a somber tone to the background of the scene.

A setting like that underscores each of the main characters’ personal problems and evokes a general atmosphere of gloom.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

When we are designing the setting of a scene, which aspect of atmosphere is more important, mood or emotion? As I have said before, both and neither because they are entwined. Our characters’ emotions affect their attitudes toward each other and influence how they view their quest. This, in turn, shapes the overall mood of the characters as they move through the arc of the plot. And the visual atmosphere of a particular environment may affect our protagonist’s personal mood. Their individual attitudes affect the emotional state of the group—the overall mood.

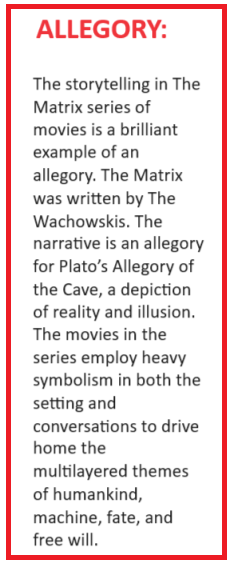

What tools in our writer’s toolbox are effective in conveying an atmosphere and a specific mood? Once we have chosen an underlying theme, it’s time to apply allegory and symbolism – two devices that are similar but different. The difference between them is how they are presented.

- Allegory is a moral lesson in the form of a story, heavy with symbolism.

- Symbolism is a literary device that uses one thing throughout the narrative (perhaps shadows) to represent something else (grief).

What are some examples? Cyberpunk, as a subgenre of science fiction, is exceedingly atmosphere-driven. It is heavily symbolic in worldbuilding and often allegorical in the narrative. We see many features of the classic 18th and 19th-century Sturm und Drang literary themes but set in a dystopian society. The deities that humankind must battle are technology and industry. Corporate uber-giants are the gods whose knowledge mere mortals desire and whom they seek to replace.

The setting and worldbuilding in cyberpunk work together to convey a gothic atmosphere, an overall feeling that is dark and disturbing. This is reflected in the subtext, which explores the dark nature of interpersonal relationships and the often criminal behaviors our characters engage in for survival.

No matter what genre we write in, we can use the setting to hint at what is to come. We can give clues by how we show the atmosphere with the inclusion of colors, scents, and ambient sounds. We choose our words carefully as they determine how the visuals are shown.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

We can create an atmosphere and mood that underscores our themes and highlights plot points without resorting to info dumps. We can lighten the mood as easily as we can darken it. When we design a setting, color brightens the visuals, and gray depresses them. Those tones affect the atmosphere and mood of the scene.

Sunshine, green foliage, blue skies, and birdsong go a long way toward lifting my spirits, so when I read a scene that is set in that kind of environment, the mood of the narrative feels lighter to me.

Worldbuilding can feel complicated when we are trying to convey subtext, mood, and atmosphere but the reader won’t be aware of the complexities. All they will know is how strongly the protagonist and her story affected them and how much they loved that novel.

Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies.

Intelligent creatures communicate in their own languages with each other, sounds that we humans interpret as random and meaningless or simply mating calls. But scientists are discovering their vocalizations must have meanings beyond attracting a mate, words that are understood by others of their kind. This is evident in the way they form herds and packs and flocks, societies with rules and hierarchies. We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government.

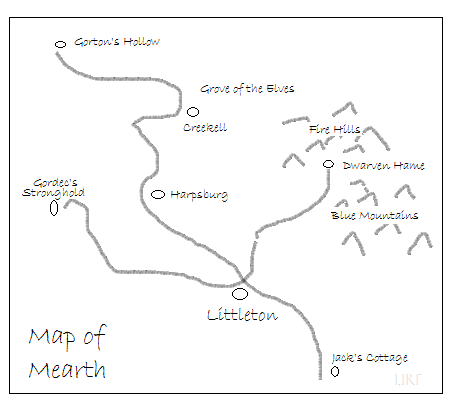

We humans are tribal. We prefer living within an overarching power structure (a society) because someone has to be the leader. We call that power structure a government. Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions.

Worldbuilding requires us to ask questions of the story we are writing. I go somewhere quiet and consider the world my characters will inhabit. I have a list of points to consider when creating a society, and you’re welcome to copy and paste it to a page you can print out. Jot the answers down and refer back to them if the plot raises one of these questions.

Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress.

Power in the hands of only a few people offers many opportunities for mayhem. Zealous followers may inadvertently create a situation where the populace believes their ruler has been anointed by the Supreme Deity. Even better, they may become the God-Emperor/Empress. Talking about the craft of writing is soothing, something with solid rules. When everything else is chaos, writing is there, offering safety and escape.

Talking about the craft of writing is soothing, something with solid rules. When everything else is chaos, writing is there, offering safety and escape. First, is this character someone the reader should remember? Even if they offer information the protagonist and reader must know, it doesn’t necessarily mean they must be named. Walk-through characters provide clues to help our protagonist complete their quest, but we never see them again. They can show us something about the protagonist and give hints about their personality or past—but when they are gone, they are forgotten.

First, is this character someone the reader should remember? Even if they offer information the protagonist and reader must know, it doesn’t necessarily mean they must be named. Walk-through characters provide clues to help our protagonist complete their quest, but we never see them again. They can show us something about the protagonist and give hints about their personality or past—but when they are gone, they are forgotten. Novelists can learn a lot from screenwriters about writing good, concise scenes. An excellent book on crafting scenes is

Novelists can learn a lot from screenwriters about writing good, concise scenes. An excellent book on crafting scenes is  I took this absurdity to an extreme in

I took this absurdity to an extreme in  One final thing to consider is this: how will that name be pronounced when read aloud? You may not think this matters, but it does. Audiobooks are becoming more popular than ever. You want to write it so a narrator can easily read that name aloud.

One final thing to consider is this: how will that name be pronounced when read aloud? You may not think this matters, but it does. Audiobooks are becoming more popular than ever. You want to write it so a narrator can easily read that name aloud. Despite my experience of reading fantasy books aloud to my children, it didn’t occur to me that the names were unpronounceable as they were written. We ironed that out, but that hiccup taught me to spell names the way they’re pronounced whenever possible.

Despite my experience of reading fantasy books aloud to my children, it didn’t occur to me that the names were unpronounceable as they were written. We ironed that out, but that hiccup taught me to spell names the way they’re pronounced whenever possible. Use common sense and if a beta reader runs amok in your manuscript telling you to remove “this and that,” examine each instance of what has their undies in a twist and try to see why they are pointing it out.

Use common sense and if a beta reader runs amok in your manuscript telling you to remove “this and that,” examine each instance of what has their undies in a twist and try to see why they are pointing it out. Many writers have beta readers look at their work before it is submitted. I would also suggest hiring a freelance editor. Besides having a person pointing out where you need to insert or delete a comma, hiring a freelance editor is a good way to discover many other things you don’t want to include in your manuscript, things you are unaware are in there:

Many writers have beta readers look at their work before it is submitted. I would also suggest hiring a freelance editor. Besides having a person pointing out where you need to insert or delete a comma, hiring a freelance editor is a good way to discover many other things you don’t want to include in your manuscript, things you are unaware are in there: Freelance editors will point out these all things. We don’t like it when certain flaws in our work are pointed out, but we are better off knowing what needs addressing. When an editor guides you away from detrimental writing habits, they aren’t trying to change your voice. They’ve seen something good in your work, and they’re pointing out places where you can tighten it up and grow as a writer.

Freelance editors will point out these all things. We don’t like it when certain flaws in our work are pointed out, but we are better off knowing what needs addressing. When an editor guides you away from detrimental writing habits, they aren’t trying to change your voice. They’ve seen something good in your work, and they’re pointing out places where you can tighten it up and grow as a writer. In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.

In creative writing, the apostrophe is a small morsel of punctuation that, on the surface, seems simple. However, certain common applications can be confusing, so as we get to those I will try to be as concise and clear as possible.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English.

The different meanings of seldom-used sound-alike words can become blurred among people who have little time to read. They don’t see how a word is written, so they speak it the way they hear it. This is how wrong usage becomes part of everyday English. Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

Insure: We insure our home and auto. In other words, we arrange for compensation in the event of damage or loss of property or the injury to (or the death of) someone. We arrange for compensation should the family breadwinner die (life insurance). Also, we arrange to pay in advance for medical care we may need in the future (health insurance).

I have a lot of words to choose from, and

I have a lot of words to choose from, and  When your spouse has Parkinson’s, problems tend to arrive en masse, like an unstoppable horde of lemmings. Dealing with life’s lemmings requires a bit more creativity than merely making a cool, relaxing drink. While you may never gain control of the migrating mob, you must somehow steer them in the right direction.

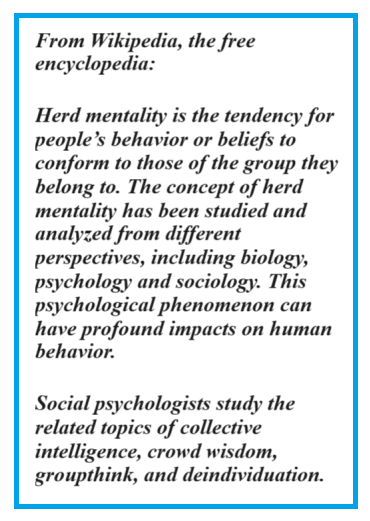

When your spouse has Parkinson’s, problems tend to arrive en masse, like an unstoppable horde of lemmings. Dealing with life’s lemmings requires a bit more creativity than merely making a cool, relaxing drink. While you may never gain control of the migrating mob, you must somehow steer them in the right direction. Wikipedia says:

Wikipedia says: But back to the lemmings. We know how mob mentality works in humans, and it seems to happen in other creatures.

But back to the lemmings. We know how mob mentality works in humans, and it seems to happen in other creatures. Two weeks ago, my husband fell, sustaining a minor injury. Two days later, he was fighting off an infection, and we spent last Saturday in Urgent Care from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm. Rather than put him in the hospital, we were given the chance to participate in the

Two weeks ago, my husband fell, sustaining a minor injury. Two days later, he was fighting off an infection, and we spent last Saturday in Urgent Care from 8:00 am to 7:00 pm. Rather than put him in the hospital, we were given the chance to participate in the  No one is perfect, but I like to do my best work. I’ll admit that publishing a post discussing a picture but with no image of that art piece is a humorous blooper. We did get a laugh out of it.

No one is perfect, but I like to do my best work. I’ll admit that publishing a post discussing a picture but with no image of that art piece is a humorous blooper. We did get a laugh out of it. I try to write my posts on Saturdays and proof them on Sundays, so having only two to deal with will allow me time to proofread them and work on my other creative writing projects.

I try to write my posts on Saturdays and proof them on Sundays, so having only two to deal with will allow me time to proofread them and work on my other creative writing projects. Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902)

Artist: Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902) When I am writing poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants and emotion words that begin with softer sounds.

When I am writing poetry, I look for words that contrast vividly against each other. I choose action words that begin with hard consonants and emotion words that begin with softer sounds. Verb choices and the use of contrast in descriptors are crucial at this stage.

Verb choices and the use of contrast in descriptors are crucial at this stage. At the end of his story, events and interactions have changed him despite his wish for a calm life. His journey through the darkness brings about a renaissance, a flowering of the spirit.

At the end of his story, events and interactions have changed him despite his wish for a calm life. His journey through the darkness brings about a renaissance, a flowering of the spirit. If I want to create an atmosphere of anxiety, I would use words that push the action outward:

If I want to create an atmosphere of anxiety, I would use words that push the action outward: That action affects both Selwyn and his objective: leaving. Away is an adverb (modifier) denoting distance from a particular person, place, or thing. It modifies the verb, giving Selwyn a direction in which to go.

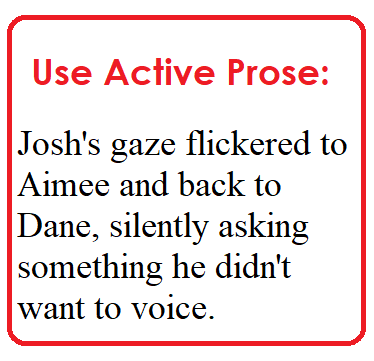

That action affects both Selwyn and his objective: leaving. Away is an adverb (modifier) denoting distance from a particular person, place, or thing. It modifies the verb, giving Selwyn a direction in which to go. The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences.

The words authors choose add depth and shape their prose in a recognizable way—their voice. They “paint” a scene showing what the point-of-view character sees or experiences. What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words.

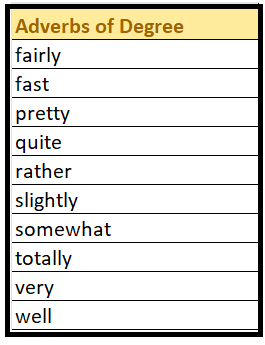

What are descriptors? Adverbs and adjectives, known as descriptors, are helper nouns or verbs—words that help describe other words. However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary.

However, if you have used “actually” to describe an object, take a second look to see if it is necessary.