Many of us are in the revision process, working on the novels we wrote during November’s NaNoWriMo. These novels are disjointed and uneven, but they contain the essence of what can be a great book—with a lot of work.

On November 1st, when we began setting the first words on the blank page, our minds formed images, scenes we attempted to describe. In his book, The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker notes that we are not born with language, so we are NOT engineered to think in words alone. We also think in images.

On November 1st, when we began setting the first words on the blank page, our minds formed images, scenes we attempted to describe. In his book, The Language Instinct, Steven Pinker notes that we are not born with language, so we are NOT engineered to think in words alone. We also think in images.

For each author, certain words become a kind of mental shorthand, code words used with frequency in the first draft because they are efficient. Code words are small packets of letters that contain a world of images and meaning for us. These words help us get the story down more quickly when we are in the grip of creativity. Code words are a speedy way to convey a wide range of information.

Because we use them, we can get the first draft of a story written from beginning to end before we lose the fire for it.

I have mentioned before that one codeword I sometimes find in my first draft prose is the word “got.” It’s a word that my family used and is ingrained in my subconsciousness as a tool word.

It is a tool word because it serves numerous purposes and conveys many images with only three letters. “Got” is on my global search list of codewords. The words in the list are signals to me, indications that a scene needs to be reworded to express my true intent.

Got can signify understanding or comprehension, as in “she got it.” Some other instances where I might use “got” as a code word for my second draft:

- He got the dog into the car. (put, placed)

- He got the mail. (acquired)

- He got (became) In an instance like this, an entire scene must be written, one I didn’t take the time to write during the rush of NaNoWriMo.

Codewords are the author’s multi-tool—a compact tool that combines several individual functions in a single unit. One little word, one small packet of letters serves many purposes and conveys a myriad of mental images.

Every author thinks differently, so your codewords will be different from mine. One way to find your secret codewords is to have the Read Aloud tool read each section. I find most of my inadvertent crutch words that way. When you hear them read aloud, they really stand out.

Once you find them, you need to go to the thesaurus to find alternatives that better express your intent.

Once you find them, you need to go to the thesaurus to find alternatives that better express your intent.

A first draft codeword high up my personal list is “felt.” Let’s go to Merriam-Webster’s Online Thesaurus:

- Synonyms:

- endured

- experienced

- knew

- saw

- suffered

- tasted

- underwent,

- witnessed

- Words Related to felt:

- regarded

- viewed

- accepted

- depended

- trusted

- assumed

- presumed

- presupposed

- surmised

We all overuse certain words without realizing it. That is where revisions come in and is where writing takes effort. You’ll discover that some words have very few synonyms that work.

When you discover one of your first draft codewords, go to the thesaurus, find all the synonyms you can, and list them in a document for easy access. If it is a word like smile or shrug, you have your work cut out, but consider making a small list of visuals.

Consider the word “smile.” It’s a common code word, a five-letter packet of visualization. We can use it to show happiness, but also it can suggest so many other moods and unspoken emotions.

Synonyms for the word smile are few and usually don’t show what I mean. When I find that word, it sometimes requires a complete revisualization of the scene. What am I really trying to convey with the word smile? I look for a different way to express my intention, which can be frustrating.

Facial expressions are only one of the many ways to display happiness, anger, spite, and other emotions. We shouldn’t rely only on a character’s face to show their moods.

Yes, their eyebrows raise or draw together, foreheads crease, and eyes sometimes twinkle. However, posture conveys a great deal. Shoulders sometimes slump, and hands often tremble. Sometimes characters refuse to look at the person they are speaking with.

Sometimes the brief image of a smile is the best expression to convey your intention.

Nothing is more off-putting than reading a story where a person’s facial expressions take center stage. As a reader, I’m more concerned with what is happening inside the characters than about the melodramatic outward display.

Think about the body language an onlooker would see if a character were angry.

- Crossed arms.

- A stiff posture.

- Narrowed eyes.

A little list of those mood indicators can keep you from losing your momentum and will readily give you the words you need to show all the vivid imagery you see in your mind.

If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. Some of the visuals they list aren’t my cup of tea, but they know how to show what people are thinking.

If you don’t have it already, a book you might want to invest in is The Emotion Thesaurus by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglisi. Some of the visuals they list aren’t my cup of tea, but they know how to show what people are thinking.

The revision process is sometimes the most challenging aspect of writing because we are also looking at scene composition and framing (which was covered in my previous post). It takes time to revisualize each scene when we are also looking for codewords and rewriting entire paragraphs.

But codewords don’t always need changing—sometimes, a smile is a smile, and that is okay.

Strolling along, watching the birds and animals that make their homes there grounds me. When we leave, I feel spiritually rested, more rooted in the earth, stronger and at peace with myself. It is a serene place, a place of stillness and calm.

Strolling along, watching the birds and animals that make their homes there grounds me. When we leave, I feel spiritually rested, more rooted in the earth, stronger and at peace with myself. It is a serene place, a place of stillness and calm. The components that form the visual layer appear to be the story. However, once a reader wades in, they discover unsuspected depths.

The components that form the visual layer appear to be the story. However, once a reader wades in, they discover unsuspected depths. The real story is how our characters interact and react to stresses within the overall framework of the environment and plot. Depth is found in the lessons the characters learn as they live through the events. Depth manifests in the changes of viewpoint and evolving differences in how they see themselves and the world.

The real story is how our characters interact and react to stresses within the overall framework of the environment and plot. Depth is found in the lessons the characters learn as they live through the events. Depth manifests in the changes of viewpoint and evolving differences in how they see themselves and the world. Foreshadowing is integral to a well-plotted story.

Foreshadowing is integral to a well-plotted story. I often refer to the way that Shakespeare used both exposition and foreshadowing. In his works, more significant events are foreshadowed through the smaller events that precede them.

I often refer to the way that Shakespeare used both exposition and foreshadowing. In his works, more significant events are foreshadowed through the smaller events that precede them. In that moment, we see that Romeo is deeply aware that he has reached a point of no return.

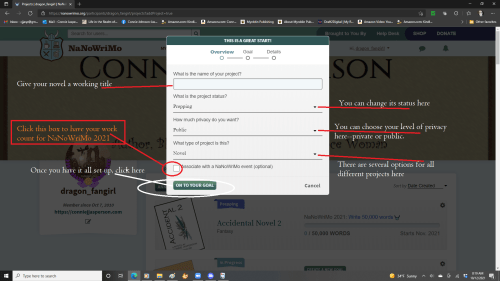

In that moment, we see that Romeo is deeply aware that he has reached a point of no return. Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and uber-creative.

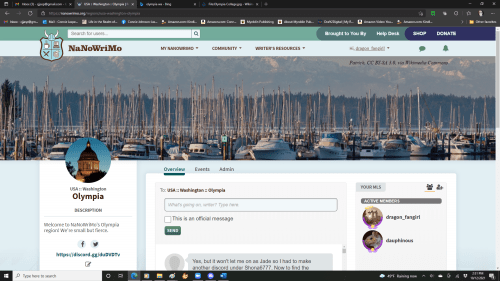

Once there, create a profile. You don’t have to get fancy unless you are bored and uber-creative. You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my Discord name and avatar. This is because I only use Discord for NaNoWriMo and one other large organization of writers. (Next week, we’ll talk about Discord and why NaNoWriMo HQ wants us to use it for word sprints and virtual write-ins.)

You can play around with your personal page a little to get used to it. I use my NaNoWriMo avatar and name as my Discord name and avatar. This is because I only use Discord for NaNoWriMo and one other large organization of writers. (Next week, we’ll talk about Discord and why NaNoWriMo HQ wants us to use it for word sprints and virtual write-ins.) Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph.

Next, check out the community tabs. If you are in full screen, the tabs will be across the top. If you have the screen minimized, the button for the dropdown menu will be in the upper right corner and will look like the blue/green and black square to the right of this paragraph. You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here.

You may find the information you need in one of the many forums listed here. Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing.

Make a master file folder that is just for your writing. I write professionally, so my files are in a master file labeled Writing. Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Accidental_Novel_2.

Give your document a label that is simple and descriptive. My NaNoWriMo manuscript will be labeled: Accidental_Novel_2. Still, we can come together and support each other’s writing via the miracle of the internet. My region is finalizing a schedule for “Writer Support” meet-ups via Zoom – little gab sessions that will connect us and keep us fired up.

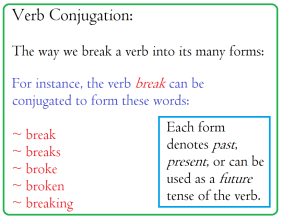

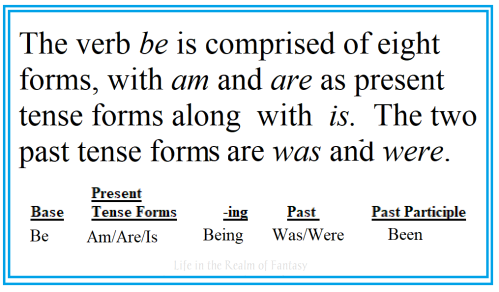

Still, we can come together and support each other’s writing via the miracle of the internet. My region is finalizing a schedule for “Writer Support” meet-ups via Zoom – little gab sessions that will connect us and keep us fired up. Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In

Today we’re discussing how narrative time, or what we call tense, affects a reader’s perception of character development. In  In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go.

In the rewrite, we look for the code words that tell us the direction in which we want the narrative to go. Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view.

Sometimes the only way you can get into a character’s head is to write them in the first-person present tense, which happened to me with Thorn Girl. I struggled with her story for nearly six months until a member of my writing group suggested changing the narrative tense and point of view. Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view.

Every story is unique, and some work best in the past tense, while others need to be in the present. When we begin writing a story using a narrative time that is unfamiliar to us, we may have trouble with drifting tense and wandering narrative points of view. Happiness, anger, spite – all the emotions get a description. Eyebrows raise or draw together; foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble. Lips turn up, lips curve down, and eyes spark – and so on and so on.

Happiness, anger, spite – all the emotions get a description. Eyebrows raise or draw together; foreheads crease and eyes twinkle; shoulders slump and hands tremble. Lips turn up, lips curve down, and eyes spark – and so on and so on. For me, the most challenging part of writing the final draft of any novel is balancing the visual indicators of emotion with the more profound, internal clues.

For me, the most challenging part of writing the final draft of any novel is balancing the visual indicators of emotion with the more profound, internal clues. I have mentioned

I have mentioned  Open the thesaurus and find words that carry visual impact in your narrative, and you won’t have to resort to a great deal of description.

Open the thesaurus and find words that carry visual impact in your narrative, and you won’t have to resort to a great deal of description. The setting is a coffee shop.

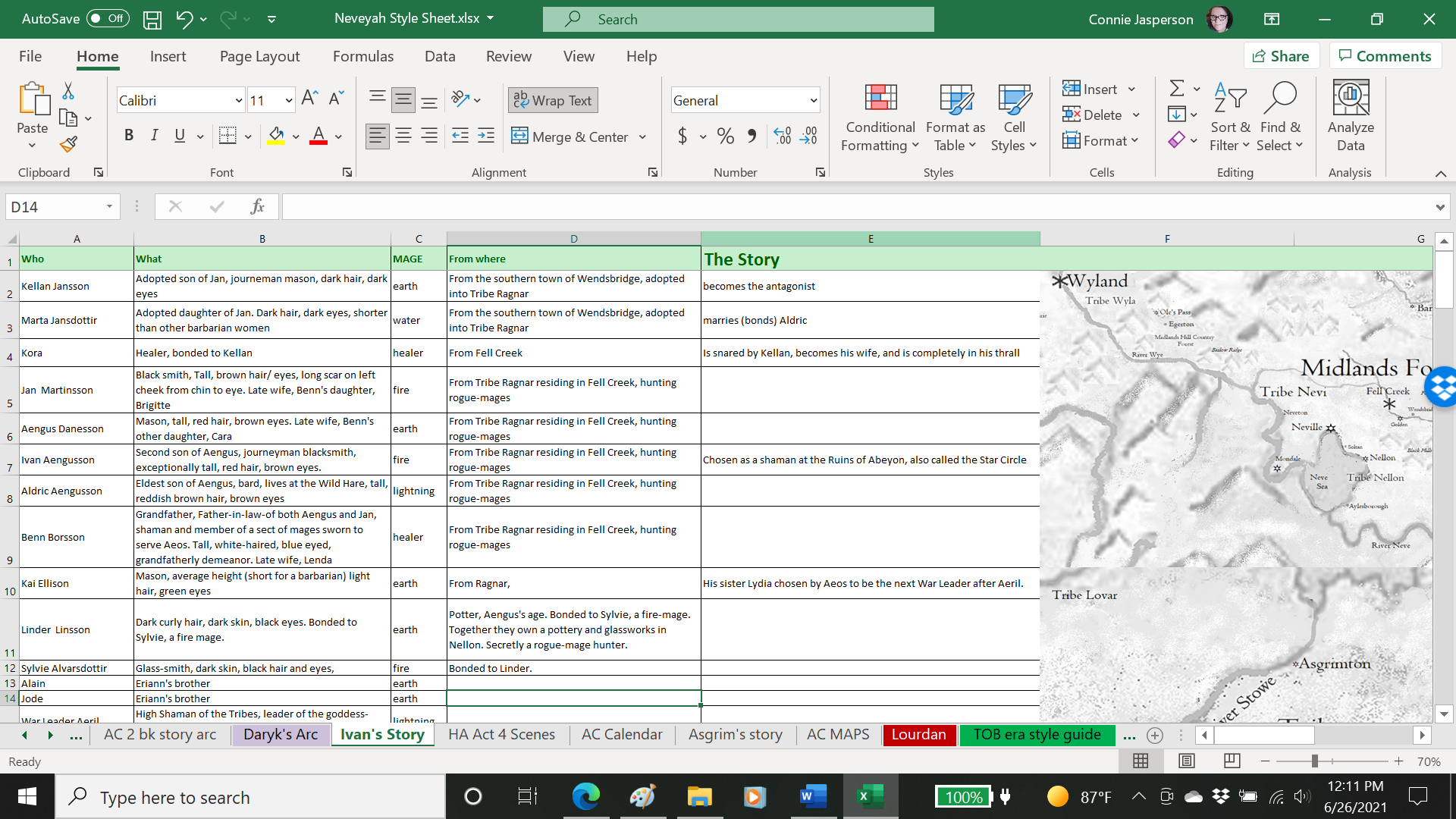

The setting is a coffee shop. If you are writing a contemporary novel or historical work set in our real world, this is where you keep maps and maybe a link to Google Earth.

If you are writing a contemporary novel or historical work set in our real world, this is where you keep maps and maybe a link to Google Earth. The “three S’s” of worldbuilding are critical: sights, sounds, and smells. Those sensory elements create what we know of the world. Taste rarely comes into it, except when showing an odor.

The “three S’s” of worldbuilding are critical: sights, sounds, and smells. Those sensory elements create what we know of the world. Taste rarely comes into it, except when showing an odor. At this moment, inside your room and outside your door, you have all the elements you need to create an alien or alternate world.

At this moment, inside your room and outside your door, you have all the elements you need to create an alien or alternate world. I think of stories as if they were ponds filled with words. A pond has layers, and so do good stories. I see the three layers of a story as:

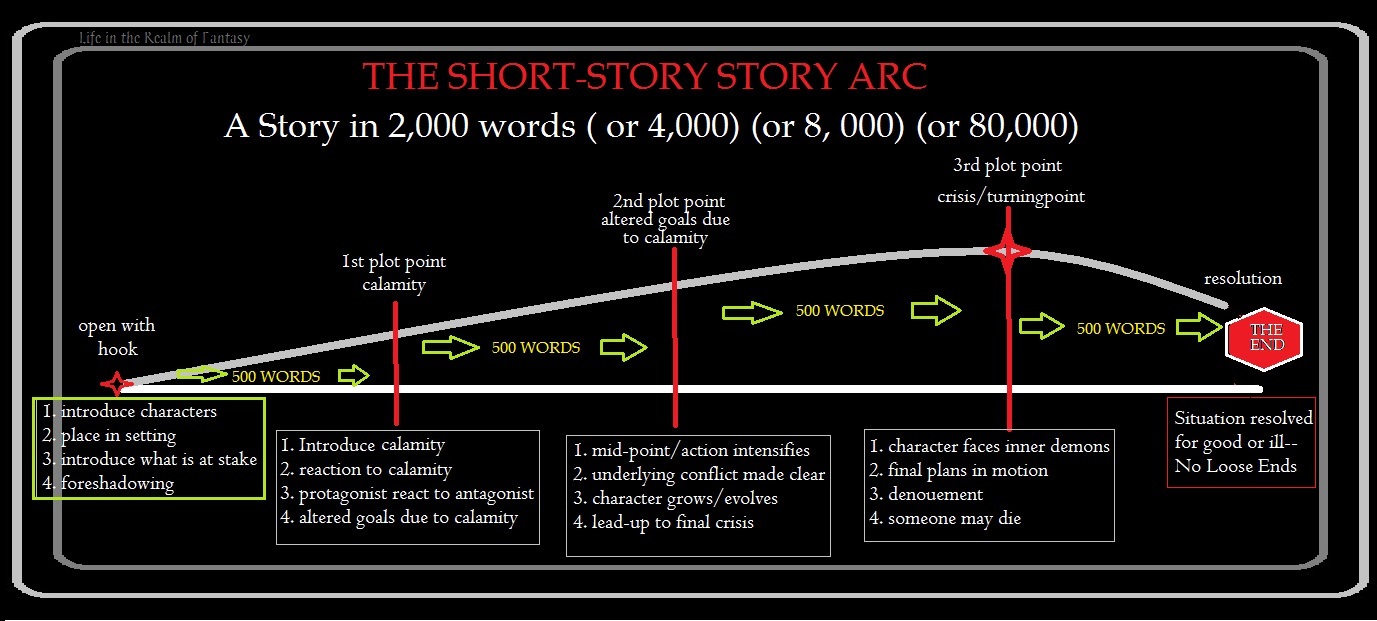

I think of stories as if they were ponds filled with words. A pond has layers, and so do good stories. I see the three layers of a story as: Act 1: the beginning: We show the setting, the protagonist, and the opening situation.

Act 1: the beginning: We show the setting, the protagonist, and the opening situation. I have mentioned before that I use a spreadsheet program to outline my projects, but you can use a notebook or anything that works for you. You can do this by drawing columns on paper by hand or using post-it notes on a whiteboard or the wall. Some people use a dedicated writer’s program like Scrivener.

I have mentioned before that I use a spreadsheet program to outline my projects, but you can use a notebook or anything that works for you. You can do this by drawing columns on paper by hand or using post-it notes on a whiteboard or the wall. Some people use a dedicated writer’s program like Scrivener. We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. The plan serves to keep us on track with length and to ensure the action doesn’t stall.

We never really know how a story will go, even if we begin with a plan. The plan serves to keep us on track with length and to ensure the action doesn’t stall. Then there is the marketing of the finished product, but that is NOT my area strength, so I won’t offer any advice on that score.

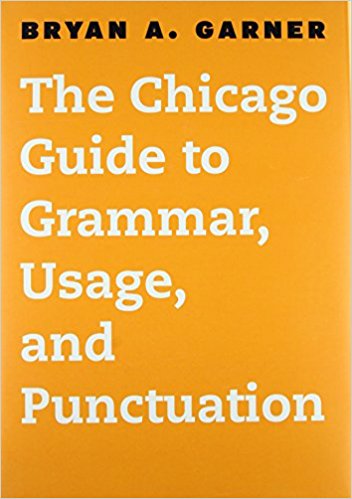

Then there is the marketing of the finished product, but that is NOT my area strength, so I won’t offer any advice on that score. If you are writing in US English, I can highly recommend getting a copy of

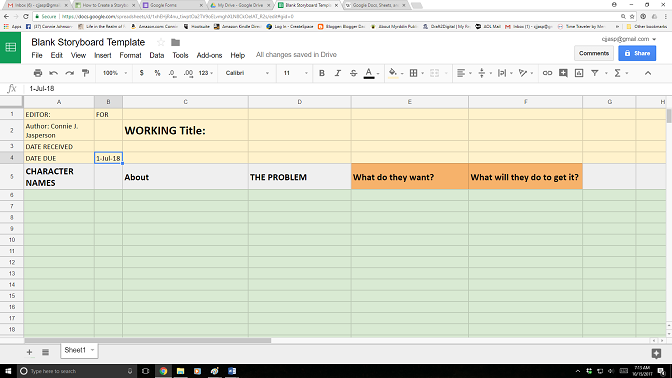

If you are writing in US English, I can highly recommend getting a copy of  Creating a

Creating a  Write the basic story. Take your characters all the way from the beginning through the middle and see that they make it to the end. If you have completed the story and have it written from beginning to end, you can concentrate on the next level of the construction phase: adding depth.

Write the basic story. Take your characters all the way from the beginning through the middle and see that they make it to the end. If you have completed the story and have it written from beginning to end, you can concentrate on the next level of the construction phase: adding depth.