The mechanics of writing are the framework that makes a story readable. Every language has specific rules for managing grammar. The language I work in is English, so if you also write in another language, you have my profound respect. You have double the work ahead of you.

Last week, we talked about how punctuation is the traffic signal that keeps our words flowing smoothly.

Last week, we talked about how punctuation is the traffic signal that keeps our words flowing smoothly.

Ellipses, em dashes, hyphens, and semicolons are rare beasts in the punctuation realm. Authors who rely on spellcheck may be getting the wrong advice when it comes to the use of rare punctuation.

For instance, Microsoft’s editor app sometimes tells us to use a comma to join two independent clauses when they don’t relate to each other. Microsoft is wrong. That creates a comma splice. The comma splice is a dead giveaway that either the author has skimped on editing their work or they’re not well-versed in grammar. (See Monday’s post, Self-editing part 1 – seven basic rules of punctuation, for a better explanation of comma splices.)

So, let’s talk about ellipses. Many authors use them incorrectly or inconsistently. This is because ellipses are not punctuation and shouldn’t be used as such.

The ellipsis is a symbol that represents omitted words and is not punctuation. The Chicago Manual of Style says that when the conversation trails off, we must add ending punctuation.

Groundfall apples, bruised and over-ripe, lay scattered across the ground. But the apple orchard is across the road, so how did they…?

Hyphens are usually not necessary, although my first drafts are often littered with them. If the meaning of a compound adjective is apparent when written as two separate words, a hyphen is not needed.

- bus stop

If the meaning is understood when two words are combined into one, and common usage writes it as one word, again a hyphen is unnecessary.

If the meaning is understood when two words are combined into one, and common usage writes it as one word, again a hyphen is unnecessary.

- afternoon

- windshield

Some combinations of “self” must have a hyphen:

- self-editing

- self-promotion

Dashes are not hyphens and are used in several ways. One kind of dash we frequently use is the ‘en dash,’ which is the width of an ‘n.’

En dashes join two numbers written numerically and not spelled out in US usage.

- 1950 – 1951

To insert an en dash in a Word document, type a single hyphen between two words and insert a space on either side (word space hyphen space word). When you hit the space bar after the second word, the dash will lengthen a little, making it slightly longer than a hyphen. UK usage often employs the en dash in the place of the em dash.

Em dashes are the width of an “m” and are the gateway to run-on sentences. To make one, key a word, and don’t hit the spacebar. Hit the hyphen key twice, then key another word, and then hit the spacebar: (word hyphen hyphen word space) word—word.

Authors sometimes use emdashes without thinking. Too many em dashes—like salt—ruin the flavor of the prose. It often works best to rephrase things a little and use a comma or a period.

But what about !? These mutant morsels of madness are called “interrobangs.”

But what about !? These mutant morsels of madness are called “interrobangs.”

Writers of comics frequently employ interrobangs to convey emotions because they have little room for prose in each panel.

More than one punctuation mark at the end of a sentence is not accepted in most other genres. Editors working in the publishing industry will tell you that the interrobang is not an accepted form of punctuation unless you write comic books, manga, or graphic novels.

It’s your narrative, so you will do as you see fit. However, interrobangs are a writing habit writers should avoid in novels and short stories if they want to be taken seriously.

Readers expect words to flow in a certain way, but no one gets it right all the time. If you choose to break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it. Voice is how you break the rules, but you must understand what you are doing and do it deliberately.

Most readers are not editors. They will either love or hate your work based on your voice, but they won’t know why.

Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said. Sometimes, you will deliberately use a comma in a place where an editor might suggest removing it. You should explain that you have done this to make something clear. Conversely, you might omit a comma for the same reason.

The editor you hired might ask you to change something you did intentionally. You are the author, and it’s your manuscript. If you know the rule you are breaking, you will be able to explain why you are doing so.

Most editors will do as you ask and will gladly ensure that you break that rule consistently.

Sometimes, the stories we consider powerful writing violate accepted grammar rules. Readers fall into the rhythm of the prose as long as the choices made for punctuation remain consistent throughout the manuscript.

One of my favorite authors, Ann McCaffrey, set off telepathic conversations with both italics and colons in the place of quote marks.

:Are you well?:

Spoken conversations in her books are punctuated using standard grammar and mechanics.

Hemmingway used commas but often connected his clauses with conjunctions.

The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.

As readers get into a story, they become habituated to the author’s style and voice. They overlook grammar no-nos because the story captivates them.

I love a good story, but more than that, I enjoy seeing how other authors write, how they think, and how their voice comes across in their work.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them. If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in  Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice. Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

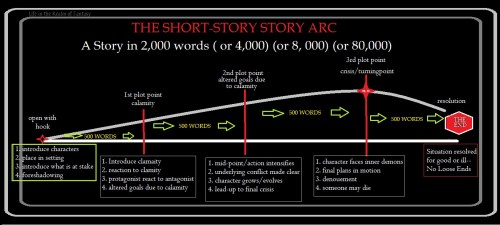

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals. So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like

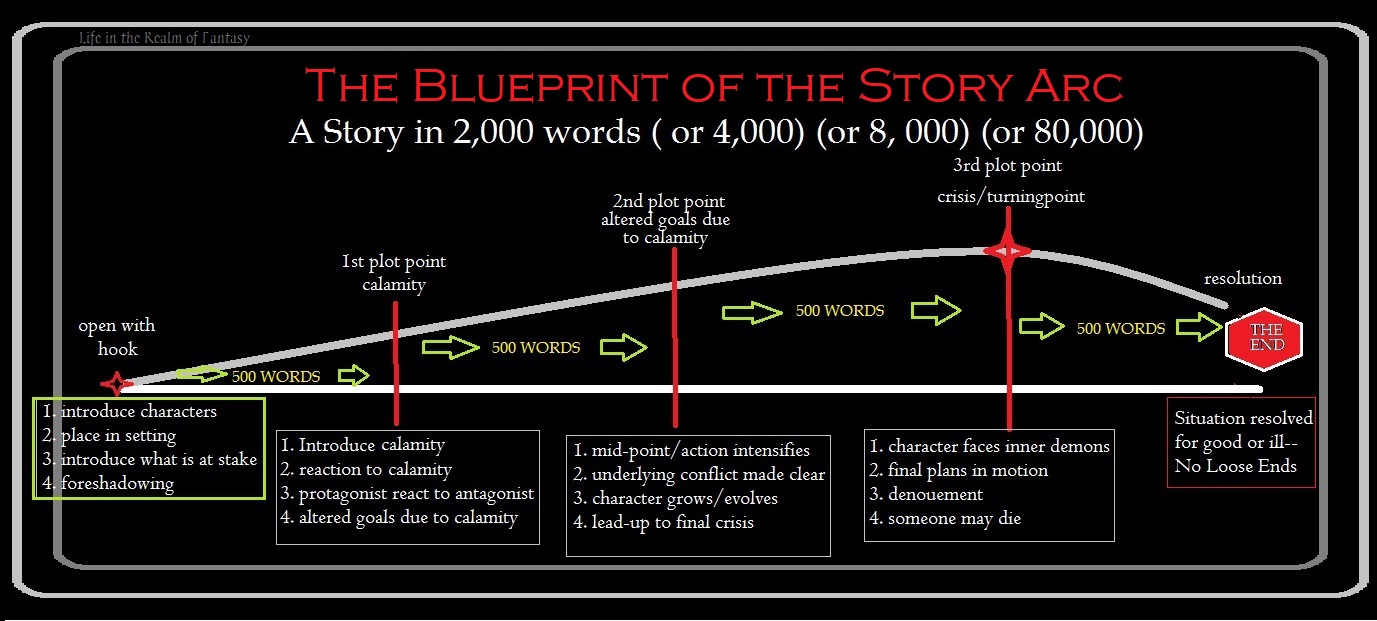

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like  The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it?

The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it? Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen.

Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen. Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories. Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it.

Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it. Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition.

Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition. When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance.

When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance. To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot!

To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot! I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript.

I do a lot of rambling in my first drafts because I’m trying to visualize the story. While I try to write this mental blather in separate documents, the random thought processes often bleed over into my manuscript. 40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark.

40,000 words in fantasy is less than half a book. That makes it a novella. But I send it to my beta reader to see what she thinks. If she feels the plot lacks substance at that length, I let it rest for a while, then come back to it. Then, I can see where to add new scenes, events, and conversations to round out the story arc. That might bring it up to the 60,000-word mark. In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery.

In the second draft, I will discover passages where I have repeated myself but with slightly different phrasing. My editor is brilliant at spotting these, which is good because I miss plenty of them when I am preparing my manuscript for editing. I wrote that mess, so even though I try to be vigilant, repetitions tend to blend into the scenery. I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut.

I have learned to be brutal. I might have spent days or even weeks writing a chapter that now must be cut. Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings.

Even if this story is one part of a series, we who are passionate about the story we’re reading need firm endings. The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson

The Emperor’s Soul, by Brandon Sanderson When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us.

When we speak aloud, we habitually use certain words and phrase our thoughts a particular way. The physiology of our throats is unique to us. While we may sound very similar to other members of our family, pitch monitoring software will show that our speaking voice is distinctive to us. Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

Flynn’s style of prose is rapid-fire, almost stream-of-consciousness, and yet it is controlled and deliberate. She is creative in how she uses the literary device of narrative mode. Primarily, Gone Girl is written in the first person present tense. But sometimes Flynn breaks the fourth wall by flowing into the second person present tense and speaking directly to us, the reader.

“I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides it was a secret.”

“I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone. Besides it was a secret.” In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story.

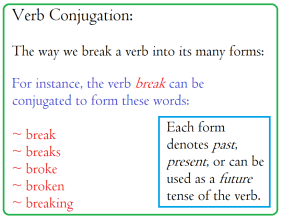

In my previous post, we talked about narrative point of view. POV is the perspective, the personal or impersonal “lens” through which we communicate our stories. It is the mode we choose for conveying a particular story. When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show.

When I begin my second draft, those weak verb forms function as traffic signals. They were a form of mental shorthand that helped me write the story before I lost my train of thought. But in the rewrite, weak verbs are code words that tell me what the scene should be rewritten to show. The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear.

The way we habitually phrase sentences, how we construct paragraphs, the words we choose, and the narrative mode and time we prefer to write in is our voice. It includes the themes we instinctively write into our work and the ideals we subconsciously hold dear. If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others.

If we move to a different window, the view changes. Some views are better than others. Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader.

Last week, I mentioned head–hopping, a disconcerting literary no-no that occurs when an author switches point-of-view characters within a single scene. I’ve noticed it happens more frequently in third-person omniscient narratives because it’s a mode in which the thoughts of every character are open to the reader. I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person.

I find that when I can’t get a handle on a particular character’s personality, I open a new document and have them tell me their story in the first person. Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel

Recognizing where the real drama begins is tricky. Let’s have a look at the novel  I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places.

I admire the audacity of having Michell, a protagonist who considers his professional reputation as his most prized possession, commit such a catastrophic action as stealing those original letters. It proves there is potential for drama in the least likely places. I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

I’m not a Romance writer, but I do write about relationships. Readers expecting a standard romance would be disappointed in my work which is solidly fantasy. The people in my tales fall in love, and while they don’t always have a happily ever after, most do. The other aspect that would disappoint a Romance reader is the shortage of smut.

In his book

In his book  When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes.

When a beta reader tells me the relationship seems forced, I go back to the basics and make an outline of how that relationship should progress from page one through each chapter. I make a detailed note of what their status should be at the end. This gives me jumping-off points so that I don’t suffer from brain freeze when trying to show the scenes. I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love.

I think our characters have to be a little clueless about Romance, even if they are older. They need to doubt, need to worry. They need to fear they don’t have a chance, either to complete their quest or to find love.