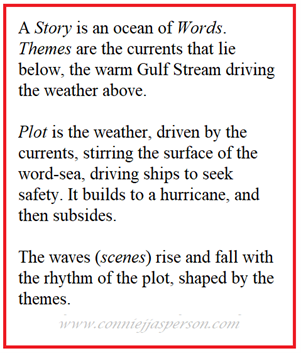

We often talk about the story arc and its component parts and features. But I often think that while a story is shaped like an arc, it is also like a pond filled with words. It is something vast and deep, set in an enclosed space.

We know our story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. We sense something murky and mysterious in the middle. We instinctively know the pond is made up of layers, although we may not consciously be aware of it or be able to explain it.

We know our story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. We sense something murky and mysterious in the middle. We instinctively know the pond is made up of layers, although we may not consciously be aware of it or be able to explain it.

Depth is a component of our story, and we will look at it over the next few posts. Depth can be a puzzle that eludes many authors, as conveying it by merely using words requires thought and a bit of extra work.

Layer one, the surface layer, is the most obvious when we look at our pond made of words. It’s what we see when we approach the shore. The surface might be calm when you look at a pond filled with water. Or, if a storm is brewing, it will be ruffled and moving.

The surface of the word pond is the literal layer. It is the what-you-see-is-what-you-get layer. This is where we find the setting, the action, and all visual/physical experiences as our characters go about their lives.

Readers choose to buy a book based on what they see when they crack it open for a brief look. They recognize what they think is there because the book is in their favorite genre, and the cover and blurb reflect that. The opening pages let them see how the author writes, and they choose to buy or move on.

Inside the book, the surface reflects the actions and events. A gun is drawn, and the weapon is fired—what happened is obvious.

We play with the surface layer by telling our story using realism, surrealism, or fantasy.

Realism is a depiction of what undisputedly is. Romance, contemporary novels, political thrillers—any narrative set in the real world without introducing fantasy elements—is realism.

Surrealism seeks to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind, for example, by the irrational juxtaposition of images—think Alice in Wonderland. It takes what is real and warps it to convey a subtler meaning.

Surrealism seeks to release the creative potential of the unconscious mind, for example, by the irrational juxtaposition of images—think Alice in Wonderland. It takes what is real and warps it to convey a subtler meaning.

Fantasy takes realism and imagines it as a different reality and world. Sometimes surreal elements are added. But a fantasy world is usually portrayed as our reality, and the fantastical elements are depicted as commonplace and ordinary.

This will be a fun layer to explore, with lots of wonderful art to help us along the way.

Back to that pond filled with words. Beneath the surface is the wide layer of an unknown quantity: the inferential layer. This is the layer where inference and implication come into play.

Perhaps at the outset, we saw a character draw a gun. This is where we show why the gun is there. We offer hints that imply reasons for the weapon being included in that scene. We show how the shooter comes to the place in the story where they squeezed the trigger.

All the characters have reasons for their actions. The author offers implications and lets the reader come to their own conclusions. The reader sees the hints, allegations, and inferences, and the underlying story of each character takes shape in their mind.

All the characters have reasons for their actions. The author offers implications and lets the reader come to their own conclusions. The reader sees the hints, allegations, and inferences, and the underlying story of each character takes shape in their mind.

In a good story, the path to the moment the trigger was pulled is complicated. Perhaps no one knows precisely what led to it, but some characters have bits of information. Your task is to fill the middle of the pond with clues, hints, and allegations. This is where INFER and IMPLY come into play.

An author implies. Readers want to solve puzzles, but they need clues. One meaning is displayed on the surface of the story. But deeper down, we enclose the true meaning, a secret folded within the narrative.

A reader infers. The reader deduces or catches the meaning of something that is not said directly by following the clues (inferences) we leave them. In reading the inferential layer of the story, they deduce the meaning of what is about to happen and receive a surge of endorphins.

They get another surge if they guessed wrong but see how it all makes sense.

No matter what genre we write, we want the reader to feel they have earned the information they are gaining. They must be able to deduce what you imply. As a listener (reader), you can only extrapolate knowledge from information someone or something has offered you.

Serious readers want this layer to mean something on a level that isn’t obvious. They want to experience that feeling of triumph for having caught the meaning. That surge of endorphins keeps them involved and makes them want more of your work.

This layer will be shallower in Romance novels because the book’s point isn’t a more profound meaning—it’s interpersonal relationships on a surface level. However, there will still be some areas of mystery that aren’t spelled out entirely because the interpersonal intrigues are the story.

This layer will be shallower in Romance novels because the book’s point isn’t a more profound meaning—it’s interpersonal relationships on a surface level. However, there will still be some areas of mystery that aren’t spelled out entirely because the interpersonal intrigues are the story.

Books for younger readers might also be less deep on this level because they don’t yet have the real-world experience to understand what is implied.

This middle layer is, in my opinion, the toughest layer for an author to get a grip on.

Below the middle Layer is Layer three, the bottom of our pond filled with words. Whatever passes from the surface travels through the middle and rests at the bottom.

This is the interpretive level:

This is the interpretive level:

- Themes

- Commentary

- Messages

- Symbolism

- Archetypes

This layer is sometimes the easiest for me to discuss because it deals with finite concepts. Theme is one of my favorite subjects to write about, as is symbolism. Commentary is something I haven’t gone into in-depth, nor have I really discussed conveying messages. Archetype is another underpinning of a story.

My personal goal is to gain a better understanding of the subtler aspects of writing as I do the research for this series. Whenever I come across a book or website with good information on these subjects, I will share it.

The commonly bandied proverbs of writing are meant to encourage us to write lean, descriptive prose and craft engaging conversations. These sayings exist because the craft of writing involves learning the rules of grammar, developing a broader vocabulary, developing characters, building worlds, etc., etc.

The commonly bandied proverbs of writing are meant to encourage us to write lean, descriptive prose and craft engaging conversations. These sayings exist because the craft of writing involves learning the rules of grammar, developing a broader vocabulary, developing characters, building worlds, etc., etc. Then, there are the stories where the author leans too heavily on the internal. Creased foreheads are replaced with stomach-churning, gut-wrenching shock or wide-eyed trembling of hands.

Then, there are the stories where the author leans too heavily on the internal. Creased foreheads are replaced with stomach-churning, gut-wrenching shock or wide-eyed trembling of hands. Indeed, we shouldn’t be married to our favorite prose or characters. Sometimes we must cut a paragraph, a chapter, or even a character we love because it no longer fits the story. But have a care – people read for pleasure. Perhaps that phrase does belong there. Maybe that arrangement of words really was the best part of that paragraph.

Indeed, we shouldn’t be married to our favorite prose or characters. Sometimes we must cut a paragraph, a chapter, or even a character we love because it no longer fits the story. But have a care – people read for pleasure. Perhaps that phrase does belong there. Maybe that arrangement of words really was the best part of that paragraph. Handy, commonly debated mantras become engraved in stone because proverbs are how we educate ourselves. Unless an author is fortunate enough to have a formal education in the subject, we must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides to learn the many nuances of the writing craft.

Handy, commonly debated mantras become engraved in stone because proverbs are how we educate ourselves. Unless an author is fortunate enough to have a formal education in the subject, we must rely on the internet and handy self-help guides to learn the many nuances of the writing craft. We have gotten a grip on my husband’s battle with

We have gotten a grip on my husband’s battle with  LSVT BIG therapy

LSVT BIG therapy Mornings usually find us wondering what we can get done that day, and evenings are often spent contemplating what could have gone better. I write whenever I can, and often end up rewriting something that seemed like a good idea at first, but which no longer works.

Mornings usually find us wondering what we can get done that day, and evenings are often spent contemplating what could have gone better. I write whenever I can, and often end up rewriting something that seemed like a good idea at first, but which no longer works. We add depth and dimension to our work layer by layer. Some layers are more abstract than others, but each layer adds an element that gives a sense of reality to the fictional world.

We add depth and dimension to our work layer by layer. Some layers are more abstract than others, but each layer adds an element that gives a sense of reality to the fictional world. The mayor likes their community’s small-town feeling and ambiance and doesn’t want it to change. Her husband is trapped, as his job is to ensure his employer gets their foot in the door. He struggled for years to rise to his current position and can’t imagine giving it up.

The mayor likes their community’s small-town feeling and ambiance and doesn’t want it to change. Her husband is trapped, as his job is to ensure his employer gets their foot in the door. He struggled for years to rise to his current position and can’t imagine giving it up. And we, the readers, desperately want our protagonist, the mayor, to get up and go to the coffeemaker. We can’t rest until we know if she either gets up and steps away from the table or someone notices the abandoned backpack and clears the meeting room.

And we, the readers, desperately want our protagonist, the mayor, to get up and go to the coffeemaker. We can’t rest until we know if she either gets up and steps away from the table or someone notices the abandoned backpack and clears the meeting room. I will have to spend a day or two thinking about the story as a whole and writing an outline as a framework to guide the story. The plot points I originally planned to occur at each of the four quarters of the story will be met, but how?

I will have to spend a day or two thinking about the story as a whole and writing an outline as a framework to guide the story. The plot points I originally planned to occur at each of the four quarters of the story will be met, but how? The midpoint of the story arc is often where the protagonists lose their faith or have a crisis of conscience. Something terrible happens, and they must learn to live with it.

The midpoint of the story arc is often where the protagonists lose their faith or have a crisis of conscience. Something terrible happens, and they must learn to live with it. So, starting at the end, I look at my characters’ location when the story finishes. Then I ask myself what they were doing just before the final encounter.

So, starting at the end, I look at my characters’ location when the story finishes. Then I ask myself what they were doing just before the final encounter. This happens even when I have an outline. I will get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious.

This happens even when I have an outline. I will get to a place where I don’t know what to write, and the characters stand around doing nothing. I repeat the same old crisis with slight variations, which is tedious. He says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?”

He says, “I rescued Lady Adeline, and the manticore is dead. Did you notice?” “Look, why don’t you sit here and watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker.

“Look, why don’t you sit here and watch TV for a while?” I park him in front of the TV and give him the clicker. “I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

“I’m sorry to bother you, but we desperately need a certain magical ingredient for my special anti-aging cream.” She looks at me expectantly. “My stepdaughter’s wedding is a big deal. But the outline says Percival and Adeline will assume the throne upon their marriage. It’s canon now, so I’m done, kicked to the curb in the prime of my life.” She dabs the corner of her squinty eyes with a silken handkerchief. “You set this story in an era where women have few career options. I simply must have my beauty cream, or I won’t be able to snare a new hubby.”

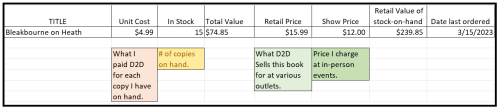

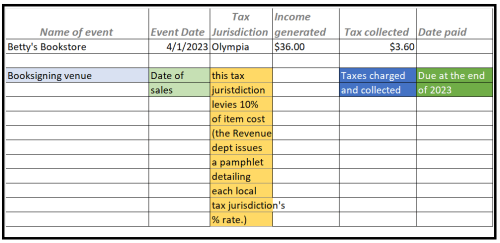

The good businessperson has a spreadsheet of some sort to account for this side of the business, as it will be part of your annual business tax report. An excellent method for assembling the information we generate for your tax report is discussed in a guest post by Ellen King Rice,

The good businessperson has a spreadsheet of some sort to account for this side of the business, as it will be part of your annual business tax report. An excellent method for assembling the information we generate for your tax report is discussed in a guest post by Ellen King Rice,  Column 4 is the sum of column three times column two: Inventory value: $89.11. That is what you would have to pay to replace those books. It is also what some Departments of Revenue may tax you on at the end of the year if the value of that stock is over a specific limit, say $5,000.00. The total value of stock-on-hand for all my books combined rarely exceeds $500.00.

Column 4 is the sum of column three times column two: Inventory value: $89.11. That is what you would have to pay to replace those books. It is also what some Departments of Revenue may tax you on at the end of the year if the value of that stock is over a specific limit, say $5,000.00. The total value of stock-on-hand for all my books combined rarely exceeds $500.00.

Depending on where you live, the natural world can be hazardous. If something should happen to your stock of books due to theft, fire, or flood, you will be able to claim your business loss.

Depending on where you live, the natural world can be hazardous. If something should happen to your stock of books due to theft, fire, or flood, you will be able to claim your business loss. At first, getting your books in front of readers is a challenge. The in-person sales event is one way to get eyes on your books. This could be at a venue as small as a local bookstore allowing you to set up a table on their premises.

At first, getting your books in front of readers is a challenge. The in-person sales event is one way to get eyes on your books. This could be at a venue as small as a local bookstore allowing you to set up a table on their premises.

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like

The final thing you will need is a way of accepting money. I have a metal cash box, but you only need something to hold cash and some bills to make change with. A way to accept credit cards, something like  I suggest buying book stands of some sort. Recipe stands work, as do plate and picture stands. Whether they’re fancy or cheap, be sure you know how to use them properly so they aren’t falling over when someone bumps the table. I use folding plate stands as they store well in the rolling suitcase I use for my supplies.

I suggest buying book stands of some sort. Recipe stands work, as do plate and picture stands. Whether they’re fancy or cheap, be sure you know how to use them properly so they aren’t falling over when someone bumps the table. I use folding plate stands as they store well in the rolling suitcase I use for my supplies. If you plan to get a table at a large conference this year, I highly recommend

If you plan to get a table at a large conference this year, I highly recommend  When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words.

When we commit to writing daily, our writing style grows and changes. When I began writing, some chapters totaled over 4,000 words. As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences.

As a reader, books work best for me when each chapter details the events of one large scene or several related events. I think of chapters as if they were paragraphs. Paragraphs are not just short blocks of randomly assembled sentences. I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with

I’ve mentioned before that one of the complaints some readers have with  Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas.

Short stories run up to 7,000 words, with under 4,000 being the most commonly requested length. 7,500–17,500 is the expected length for novelettes, and between 17,500 and 40,000 words are the standard length for novellas. In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative.

In my work, the first draft is really more of an expanded outline, a series of scenes that have characters doing things. But those scenes need to be connected so each flows naturally into the next without jarring the reader out of the narrative. We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill.

We are always told, “Don’t waste words on empty scenes.” I find this part of the revision process the most difficult. Frankly, I have a million words at my disposal, and wasting them is my best skill. If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene.

If you ask a reader what makes a memorable story, they will tell you that the emotions it evoked are why they loved that novel. They were allowed to process the events, given a moment of rest and reflection between the action. Our characters can take a moment to think, but while doing so, they must be transitioning to the next scene. Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft.

Visual Cues: In my own work, when I come across the word “smile” or other words conveying a facial expression or character’s mood, it sometimes requires a complete re-visualization of the scene. I’m forced to look for a different way to express my intention, which is a necessary but frustrating aspect of the craft.