This week we’re continuing our dive into character building. I’m putting my beta reader’s comments to work, trying to iron out some of the rough patches, and one that I must work on is attraction.

Writing emotions with depth is a balancing act. This is where I write from real life. I think about the physical cues I see when my friends and family feel emotion. When someone is happy, what do you see? Bright eyes, laughter, and smiles.

Writing emotions with depth is a balancing act. This is where I write from real life. I think about the physical cues I see when my friends and family feel emotion. When someone is happy, what do you see? Bright eyes, laughter, and smiles.

And when we’re happy, how do we feel? Energized, confident. We’re always slightly giddy when we have a little crush coming on and even happier when it blossoms into a romance.

The trick is to combine the surface of the emotion (physical) with the deeper aspect of the feeling (internal). Not only that, but we want to write it so that we aren’t telling the reader what to experience. We allow the reader to experience the emotion as if it is their idea.

Fantasy is a popular genre because it involves people. People are creatures of biology and emotion. When you throw them together in close quarters, romances can happen within the narrative.

I’m not a Romance writer. I write about relationships, but Romance readers will be disappointed in my work. My tales don’t always have a happily ever after, although most do. Also, while I can be graphic, I’m usually a fade-to-black kind of writer, allowing my characters a little privacy.

I flounder when writing without an outline, and even though I’m in the second draft, I’m floundering now.

Writing intense, heartfelt emotions is easy for me. I begin to have trouble when I attempt to write the subtler nuances of attraction and its opposite, repulsion. I find myself at a loss for words.

The problem is, if you write intense emotions with no buildup, they come out of nowhere and seem gratuitous.

So, how do I foreshadow these relationships and show the buildup? I go to Romance writers and ask questions. I’ve attended workshops given by romance writers and learned a great deal from them. However, being autistic, I understand more from pursuing independent study.

Also, I’m a book junkie—I can’t pass up buying any book on the craft of writing. I bought two books on writing craft by Damon Suede, who writes Romance. These two books show how word choices can make or break the narrative.

Also, I’m a book junkie—I can’t pass up buying any book on the craft of writing. I bought two books on writing craft by Damon Suede, who writes Romance. These two books show how word choices can make or break the narrative.

In his book Verbalize, he explains how actions make other events possible. Even gentler, softer emotions must have verbs to set them in motion.

Emotions are nouns, and so I need to find and use the right verbs to activate them.

Therefore, matching nouns with verbs is key to bringing that romance to life. I must get out the dictionary of synonyms and antonyms and delve into the many words that relate to and describe attraction. ATTRACTION Synonyms: 33 Synonyms & Antonyms for ATTRACTION | Thesaurus.com

So, now that I have all these lovely words, the next step is to choose the words that say what I mean and fit them into the narrative.

This novel was accidental, so I didn’t plan the relationships out the way I usually do. I have five people in this convoluted tale. I’m a bookkeeper, so doing the math, if we end up with two couples, one character will be left out.

Now my beta readers tell me that while the final matches work, I need to hint at sexual tension from the opening pages on to better show the attraction.

Also, they pointed out that the odd-one-out creates endless opportunities for a real roadblock to the final event. This is something I hadn’t seen, but wow–what a great way to inject some power into the finale.

Each of us experiences emotional highs and lows in our daily lives. We have deep-rooted, personal reasons for our emotions, for whether we are attracted to or repulsed by another person. Sometimes those interactions can be highly charged.

Each of us experiences emotional highs and lows in our daily lives. We have deep-rooted, personal reasons for our emotions, for whether we are attracted to or repulsed by another person. Sometimes those interactions can be highly charged.

Both the protagonist and the antagonist must have legitimate reasons for their actions and reactions. There must be a history of some sort. Failing that, there must be an instinctive attraction/rejection.

Our characters must have credible responses that a reader can empathize with, and there must be consequences.

For me, this is where writing becomes work.

Each character should have an arc of growth and change as the story progresses. Heroes that arrive fully formed on page one are boring. For me, the characters are the story, and the events of the piece exist only to force growth upon them.

Each character should have an arc of growth and change as the story progresses. Heroes that arrive fully formed on page one are boring. For me, the characters are the story, and the events of the piece exist only to force growth upon them. Bilbo resents both the intrusion and being made aware of how bored he is. Secretly, he fears going into the unknown and resists Gandalf’s insistence that he must go with the dwarves. However, at the last minute, Bilbo realizes that if he doesn’t go now, he will always wonder what would have happened if he had.

Bilbo resents both the intrusion and being made aware of how bored he is. Secretly, he fears going into the unknown and resists Gandalf’s insistence that he must go with the dwarves. However, at the last minute, Bilbo realizes that if he doesn’t go now, he will always wonder what would have happened if he had. Over the next year, Bilbo experiences many things. Where once he was a little xenophobic and slightly disdainful of anything not of The Shire, he discovers that other cultures are as valuable as his, meeting people of different races whom he comes to love and trust. He experiences the loss of friends and gains compassion. By the time Bilbo returns to the Shire, he is a different person than he was when he ran out his front door without even a handkerchief.

Over the next year, Bilbo experiences many things. Where once he was a little xenophobic and slightly disdainful of anything not of The Shire, he discovers that other cultures are as valuable as his, meeting people of different races whom he comes to love and trust. He experiences the loss of friends and gains compassion. By the time Bilbo returns to the Shire, he is a different person than he was when he ran out his front door without even a handkerchief.

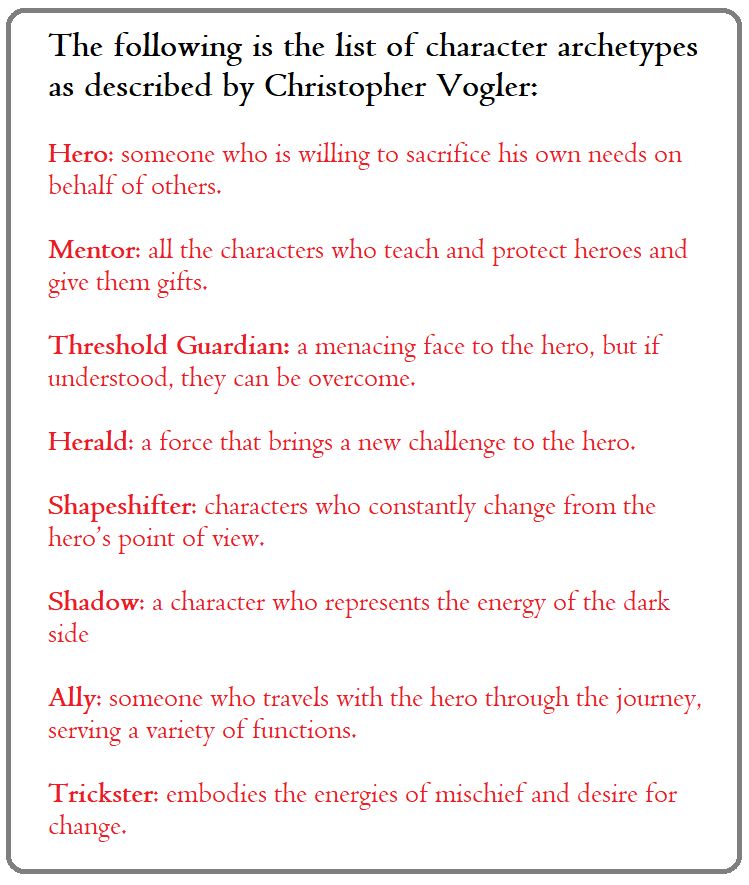

The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers,

The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, One thing I do recommend is that you keep the number of allies limited. Too many named characters can lead to confusion in the reader.

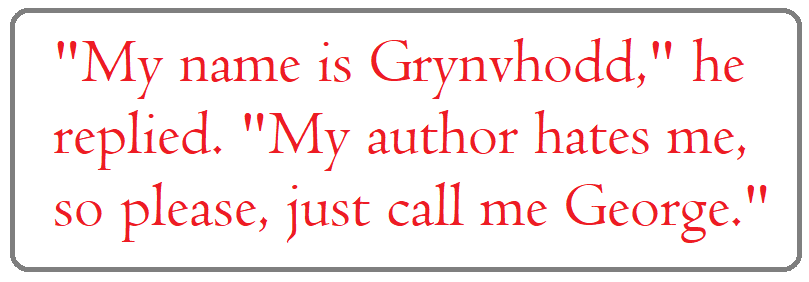

One thing I do recommend is that you keep the number of allies limited. Too many named characters can lead to confusion in the reader. How easy is it to read, and how will that name be pronounced when it is read aloud?

How easy is it to read, and how will that name be pronounced when it is read aloud? In real life, everyone has emotions and thoughts they conceal from others. Perhaps they are angry and afraid, or jealous, or any number of emotions we are embarrassed to acknowledge. Maybe they hope to gain something on a personal level—if so, what? Small hints revealing those unspoken motives are crucial to raising the tension in the narrative.

In real life, everyone has emotions and thoughts they conceal from others. Perhaps they are angry and afraid, or jealous, or any number of emotions we are embarrassed to acknowledge. Maybe they hope to gain something on a personal level—if so, what? Small hints revealing those unspoken motives are crucial to raising the tension in the narrative. Dialogue gives shape to the story, turning what could be a wall of words into something personal. We meet and get to know our protagonists and the people they will travel with through the conversations they engage in.

Dialogue gives shape to the story, turning what could be a wall of words into something personal. We meet and get to know our protagonists and the people they will travel with through the conversations they engage in. Obi-Wan is a complex mentor, arriving on the screen with a past. He has lived and lost and made choices he wished he hadn’t. When he faces Darth Vader in his final showdown, you get the feeling that the old man planned his exit perfectly.

Obi-Wan is a complex mentor, arriving on the screen with a past. He has lived and lost and made choices he wished he hadn’t. When he faces Darth Vader in his final showdown, you get the feeling that the old man planned his exit perfectly. For this reason, every sacrifice our characters make must have meaning and must advance the plot, or you have wasted the reader’s precious time.

For this reason, every sacrifice our characters make must have meaning and must advance the plot, or you have wasted the reader’s precious time. Mortally wounded, the antagonist, Khan, activates a “rebirth” weapon called Genesis, which will reorganize all matter in the nebula, including Enterprise. Though Kirk’s crew detects the activation and attempts to move out of range, they will not be able to escape the nebula in time without the ship’s inoperable warp drive. Spock goes to restore warp power in the engine room, which is flooded with radiation. When McCoy tries to prevent Spock’s entry, Spock incapacitates him with a

Mortally wounded, the antagonist, Khan, activates a “rebirth” weapon called Genesis, which will reorganize all matter in the nebula, including Enterprise. Though Kirk’s crew detects the activation and attempts to move out of range, they will not be able to escape the nebula in time without the ship’s inoperable warp drive. Spock goes to restore warp power in the engine room, which is flooded with radiation. When McCoy tries to prevent Spock’s entry, Spock incapacitates him with a  Maybe that moment in time that we long for didn’t shine with the golden glow that the mirror of memory now gives it. Nevertheless, we hope to feel that innocent happiness that we will never experience again.

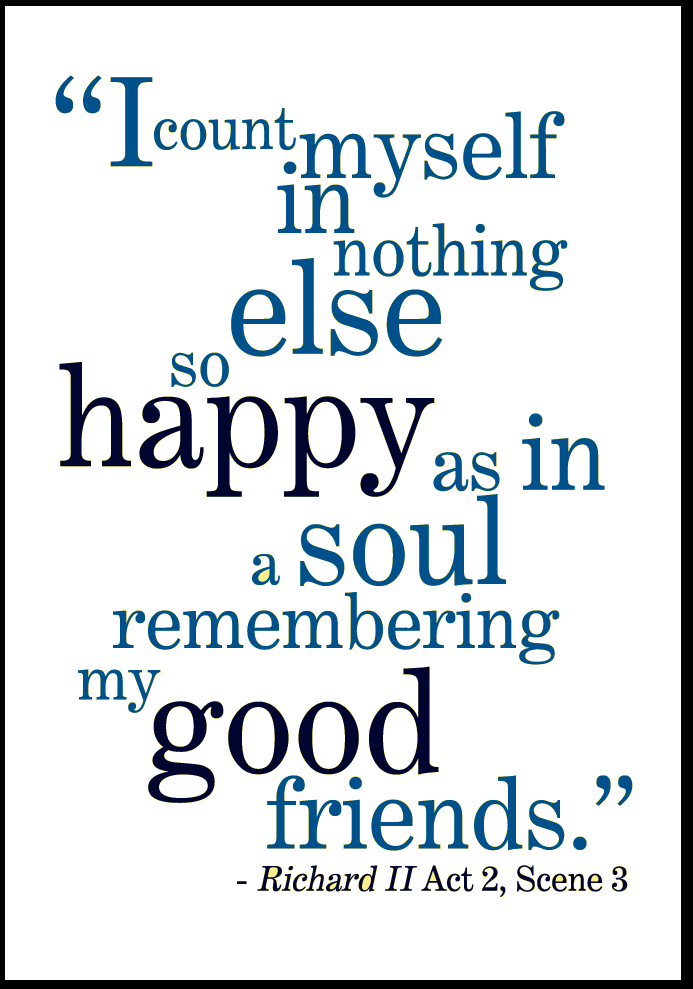

Maybe that moment in time that we long for didn’t shine with the golden glow that the mirror of memory now gives it. Nevertheless, we hope to feel that innocent happiness that we will never experience again. In the scene at the Prancing Pony, Aragorn is quoting a poem that is later revealed to reference him as the Heir of Isildur. He is the prophesied king who will once again wield the Blade that was Broken. These are wise words from a poem-within-the-story, a signature literary device Tolkien used regularly.

In the scene at the Prancing Pony, Aragorn is quoting a poem that is later revealed to reference him as the Heir of Isildur. He is the prophesied king who will once again wield the Blade that was Broken. These are wise words from a poem-within-the-story, a signature literary device Tolkien used regularly. As I create my mentors, I hope to convey a sense that they have history without beating the reader over the head with it. I want to evoke a feeling of rightness, that this person knows things we don’t, that this person has knowledge our protagonist must gain.

As I create my mentors, I hope to convey a sense that they have history without beating the reader over the head with it. I want to evoke a feeling of rightness, that this person knows things we don’t, that this person has knowledge our protagonist must gain. Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they aren’t necessarily factual or accurate representations of events. They often detail a fictionalized experience or event that affected the author on a personal level.

Narrative essays are drawn directly from real life, but they aren’t necessarily factual or accurate representations of events. They often detail a fictionalized experience or event that affected the author on a personal level. Choose your words for impact! Writing with intentional prose is critical. A good essay has been put into an entertaining form that expresses far more than mere opinion. Narrative essays sometimes present deep, uncomfortable concepts but offer them in a way that the reader feels connected to the story.

Choose your words for impact! Writing with intentional prose is critical. A good essay has been put into an entertaining form that expresses far more than mere opinion. Narrative essays sometimes present deep, uncomfortable concepts but offer them in a way that the reader feels connected to the story. And on that note, we must be realistic. Not everything you write will resonate with everyone you submit it to. Put two people in a room, hand them the most exciting thing you’ve ever read, and you’ll get two different opinions. They probably won’t agree with you.

And on that note, we must be realistic. Not everything you write will resonate with everyone you submit it to. Put two people in a room, hand them the most exciting thing you’ve ever read, and you’ll get two different opinions. They probably won’t agree with you. Editors at magazines, contests, and publishing houses have no time to deal with poorly formatted manuscripts. Their inboxes are full of properly formatted work, so they will reject the amateurs without further consideration.

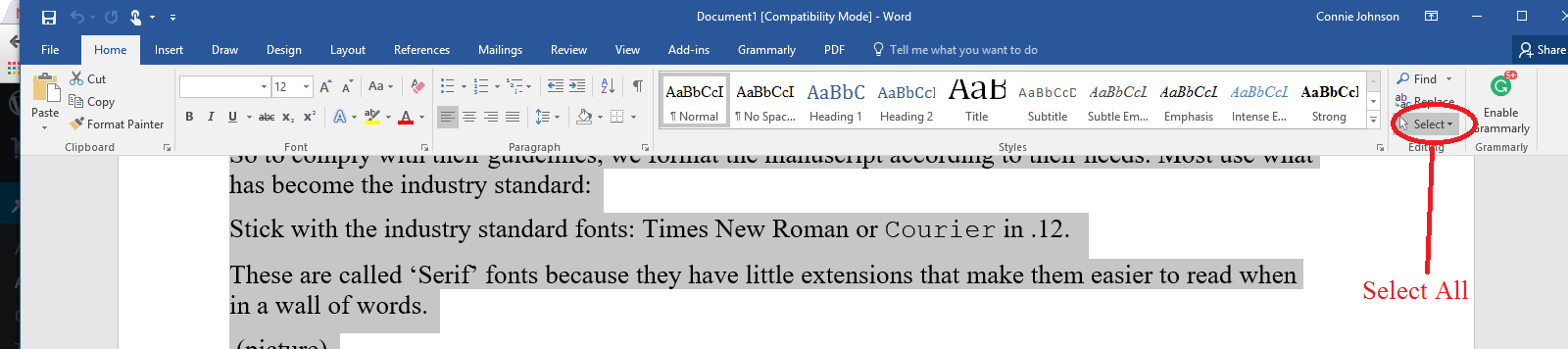

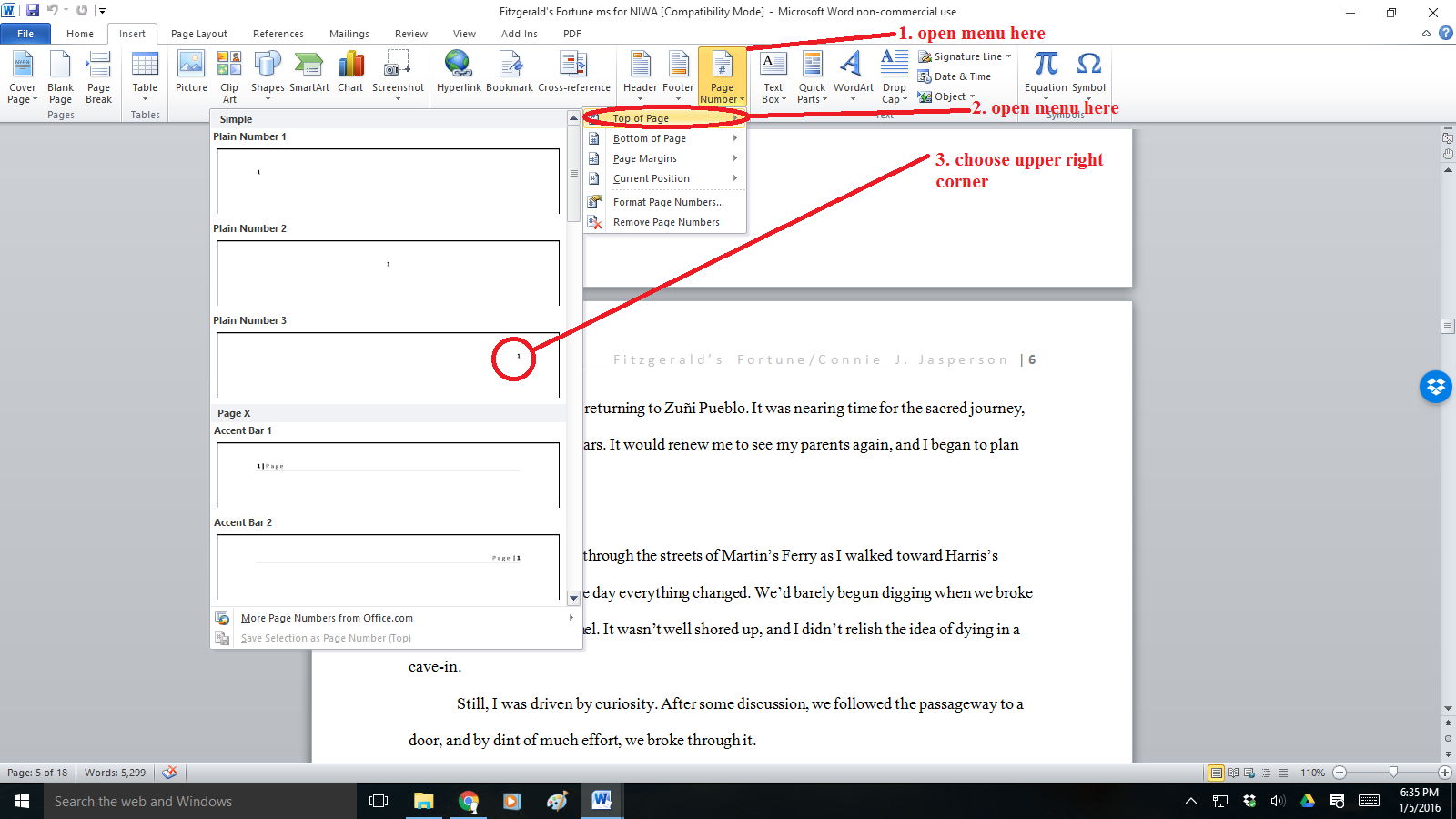

Editors at magazines, contests, and publishing houses have no time to deal with poorly formatted manuscripts. Their inboxes are full of properly formatted work, so they will reject the amateurs without further consideration. First, we must select the font. Every word-processing program has many fancy fonts you can choose from and a variety of sizes.

First, we must select the font. Every word-processing program has many fancy fonts you can choose from and a variety of sizes. Step 1: On the Home tab, look in the group labeled ‘Paragraph.’ On the lower right-hand side of that group is a small grey square. Click on it. A pop-out menu will appear, and this is where you format your paragraphs.

Step 1: On the Home tab, look in the group labeled ‘Paragraph.’ On the lower right-hand side of that group is a small grey square. Click on it. A pop-out menu will appear, and this is where you format your paragraphs. Do not justify the text. In justified text, the spaces between words and letters (known as “tracking”) are stretched or compressed. Justified text gives you straight margins on both sides. However, this type of alignment only comes into play when a manuscript is published. At that point, the publisher will handle the formatting.

Do not justify the text. In justified text, the spaces between words and letters (known as “tracking”) are stretched or compressed. Justified text gives you straight margins on both sides. However, this type of alignment only comes into play when a manuscript is published. At that point, the publisher will handle the formatting. Now your manuscript is submission-ready. It is in Times New Roman or Courier .12 font, is aligned left, has1 in. margins, is double-spaced, has formatted indented paragraphs.

Now your manuscript is submission-ready. It is in Times New Roman or Courier .12 font, is aligned left, has1 in. margins, is double-spaced, has formatted indented paragraphs. This may seem like overkill to you. If you are serious about submitting your work to agents, editors, or publishers, it must be as professionally formatted as is possible.

This may seem like overkill to you. If you are serious about submitting your work to agents, editors, or publishers, it must be as professionally formatted as is possible. You are more likely to sell a drabble than a short story in today’s speculative fiction market. You are also more likely to sell a short story than a novel.

You are more likely to sell a drabble than a short story in today’s speculative fiction market. You are also more likely to sell a short story than a novel. does require plotting and rewriting the prose until the entire story is told in exactly 100 words. You should expect to spend an hour or so writing and then editing it to fit within the 100-word constraint.

does require plotting and rewriting the prose until the entire story is told in exactly 100 words. You should expect to spend an hour or so writing and then editing it to fit within the 100-word constraint. The above drabble is a 100-word romance and is an example I have used here before. It has a beginning (hook), a middle (the conflict), and a resolution. The opening shows our protagonist on the beach with someone for whom she cares deeply.

The above drabble is a 100-word romance and is an example I have used here before. It has a beginning (hook), a middle (the conflict), and a resolution. The opening shows our protagonist on the beach with someone for whom she cares deeply. The act of writing random ideas and emotions down in drabble form rejuvenates your creativity, a mini-vacation from your other work. It rests your mind and clears things so you can return to your main project with all your attention.

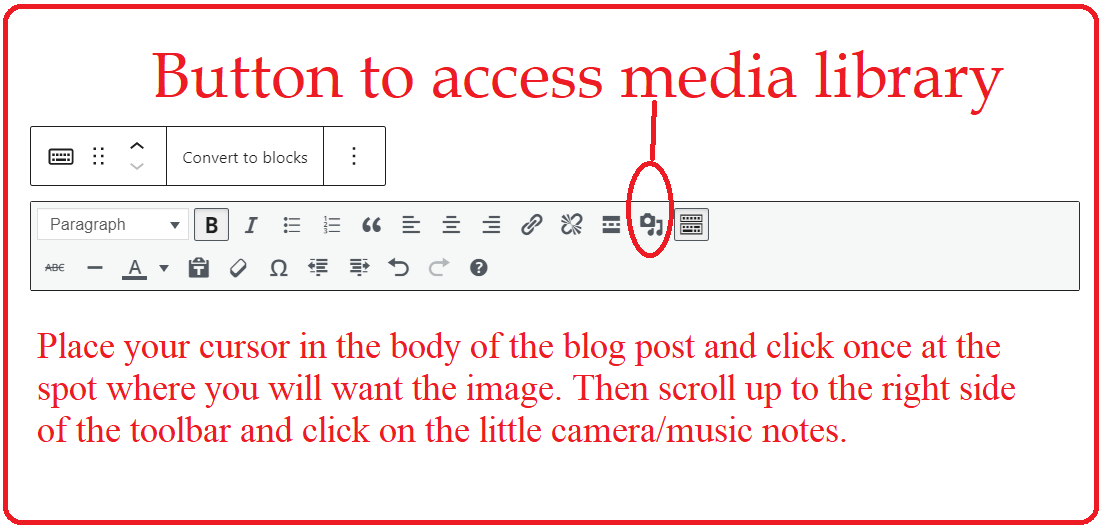

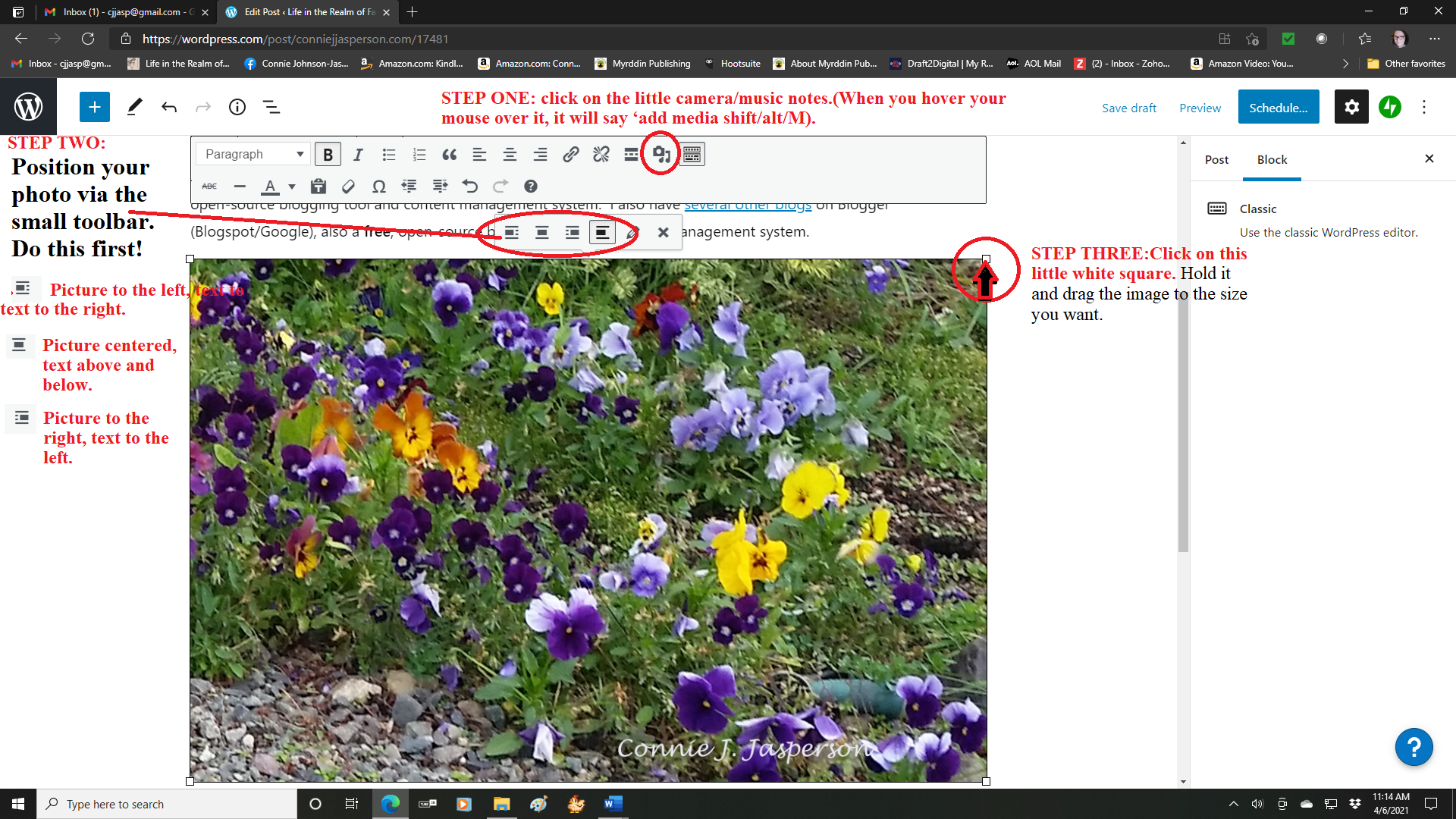

The act of writing random ideas and emotions down in drabble form rejuvenates your creativity, a mini-vacation from your other work. It rests your mind and clears things so you can return to your main project with all your attention. I prefer Blogger for ease of use, but I love the way WordPress looks when you get to the finished product stage. I do pay an annual fee to both WordPress and Blogger so that my readers aren’t subjected to random and sometimes obscene-looking advertisements.

I prefer Blogger for ease of use, but I love the way WordPress looks when you get to the finished product stage. I do pay an annual fee to both WordPress and Blogger so that my readers aren’t subjected to random and sometimes obscene-looking advertisements.

So, now that we are clear as to our legal responsibility, what does the cash-strapped author do? I go to Wikimedia and use images that are in the public domain, and I also create my own graphics.

So, now that we are clear as to our legal responsibility, what does the cash-strapped author do? I go to Wikimedia and use images that are in the public domain, and I also create my own graphics. I keep a log of where my images are sourced, who created them, and what I used them in. One thing WordPress has either removed or hidden is the ability to insert the attribution into the image details so that when a mouse hovered over the image, curious readers could go to the source. But that doesn’t seem to be an option any more.

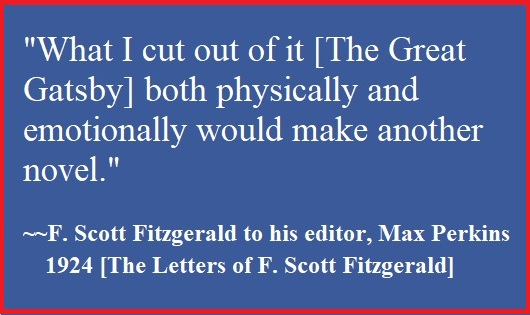

I keep a log of where my images are sourced, who created them, and what I used them in. One thing WordPress has either removed or hidden is the ability to insert the attribution into the image details so that when a mouse hovered over the image, curious readers could go to the source. But that doesn’t seem to be an option any more. All this information for your images and any quotes from other sources should be listed at the BOTTOM of your current document as you find it, so everything you need for your blog post is all in one place.

All this information for your images and any quotes from other sources should be listed at the BOTTOM of your current document as you find it, so everything you need for your blog post is all in one place.