Many of my blog posts revolve around grammar and the mechanics of writing. As authors, it’s important to understand the rules of the language in which we write. Yet, powerful writing often breaks those rules, and we are better for having read it.

So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it.

So why am I always pressing you to use proper punctuation? Authors must know the rules to break them with style. Readers expect words to flow in a certain way. If you break a grammatical rule, be consistent about it.

We who are serious about the craft of writing attend critique groups, and we submit our best work. At first, we feel bombarded with reprimands, spotlights highlighting the flaws in our beloved narrative.

- Show it, don’t tell it.

- Simplify, simplify.

- Don’t write so many long sentences.

- Don’t be vague—get to the point.

- Don’t use “ten-dollar words.”

- Cut the modifiers—they muck up your narrative.

These comments are painful but necessary. Putting this knowledge to work enables us to produce work our readers will find enjoyable.

However, all rules can be taken to an extreme. I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating. The most important rules are:

- Trust yourself,

- Trust your reader.

- Be consistent.

- Write what you want to read.

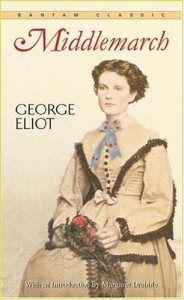

Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice.

Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Alexander Chee, and George Saunders all have unique voices in their writing. Each of these writers has written highly acclaimed work. Their prose is magnificent. When you have fallen in love with an author’s work, you will recognize their voice.

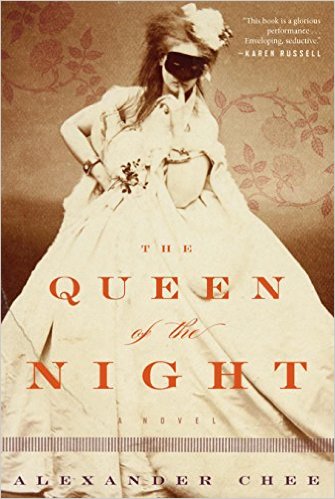

Ernest Hemingway used commas freely, passing them around in his narratives like party favors. Alexander Chee employs sentences that run on forever and doesn’t use quotation marks when writing dialogue.

James Joyce wrote hallucinogenic prose and, at times, dispensed with punctuation altogether.

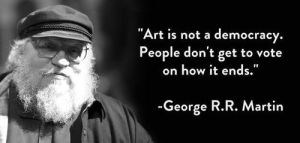

George Saunders writes as if he is speaking to you and is, at times, choppy in his delivery.

But their voices work because they know the kind of reader they are writing for. Each of the above authors breaks those rules consistently, and their work stands the test of time. Readers fall into the rhythm of their prose.

I HAVE A CONFESSION. I had to take a college class to understand James Joyce’s work.

Also, I grew frustrated and resorted to listening to the audiobook of Alexander Chee’s The Queen of the Night. Not setting dialogue apart with quotes? AAAAAAUGH!!! I’m an editor, and it’s my job to notice those things. It’s difficult for me to set that part of my awareness aside, but the audiobook resolved that issue.

I can hear the grumbles now. I just mentioned literary authors, and you are writing a cozy mystery, a fantasy, a romance, women’s fiction, or sci-fi. Shall I toss out a few more names?

Tad Williams mixes his styles. His Bobby Dollar series is Paranormal Film Noir: dark, choppy, and reminiscent of Sam Spade. In this series, he seems to be somewhat influenced by the style of crime authors, such as Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. Each installment is a quick read for me and is commercial in that casual readers would enjoy Bobby’s predicaments as much as I did.

Tad Williams mixes his styles. His Bobby Dollar series is Paranormal Film Noir: dark, choppy, and reminiscent of Sam Spade. In this series, he seems to be somewhat influenced by the style of crime authors, such as Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett. Each installment is a quick read for me and is commercial in that casual readers would enjoy Bobby’s predicaments as much as I did.

Yet Tad’s Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn Trilogy was a groundbreaking series that inspired countless fantasy authors. Those first three books and the subsequent novels set in that world are solidly epic fantasy. They are written for serious fantasy readers, people who want big stories set in big worlds.

These readers like BIG books. In that series, Tad Williams employs lush prose, multiple storylines, and dark themes. Beginning slow and working up to an epic ending is highly frowned upon in local writing groups, but Tad broke that rule, and believe me, it works. His powerful writing has generated millions of fans who are thrilled that he’s written more work in that amazing world.

Roger Zelazny wrote one of the most famous fantasy series of all time, the Chronicles of Amber, and was famous for his crisp, minimalistic dialogue. The style of his contemporary wisecracking, hardboiled crime authors also influenced him.

Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

Craft your work to make it say what you intend in the way you want it said, but be prepared to defend your choices if you deviate too widely from the expected.

Sometimes, I feel married to a particular passage, and it breaks my heart when someone points out that my beautifully crafted passage adds nothing to the narrative.

The fact is, some words and phrases are distracting. It is easy to fluff things up with descriptors and modifiers, which only increase the wordiness. Those mucky morsels are known as “weed words,” and I make an effort to cut them before my editor sees them, as she will gladly point out each one in a sea of red.

There will be times when you choose to use a comma in a place where an editor might suggest removing it. If asked, you should explain that you have done this to make something clear. Conversely, you might omit a comma for the same reason.

An editor might ask you to change something you did intentionally. Remember, you are the author, and it’s your manuscript. If you know the rule you are breaking, you will be able to explain why you are doing so.

Most editors will gladly ensure that you break that rule consistently—mine surely does.

Voice is how you break the rules. When you understand what you are doing and do it deliberately, your work will convey the story to the reader in the way you want.

The great blessing for those of us who pull novels out of our souls is this: the majority of readers are not editors or professional writers. Readers will either love or hate your work based on your voice, but they won’t know why.